< Previous | Contents | Next >

THE CHURCH.

Tollerton church from the south.

Tollerton church from the south.The Domesday Rook mentions a Church in this village in the eleventh century. This Church may have stood for many years before the Survey was made. Allusion has been made to a tradition that there was a Church at the north end of the village. There are considerations which make us hesitate to reject this tradition; and it is possible that before the Barrys settled here the Saxon Church of 1086 was at the north end of the village, near the moated enclosure.

Whether or no this was the case, we have good ground for believing that a Church has stood on the present site since the 12th or 13th century. The piscina must have belonged to a late Norman Church, but that is the solitary witness left of such a building. A few remains of 13th century work have been spared to us by the devastators of the 19th century. Archaeologists account the two arcades of arches, and some of the pillars to be 13th century work. Fragments of the walls, notably of the north aisle, are apparently of that period; and when the stucco is removed, much of the ancient work may yet be revealed. The blocked up window at the east end of the north aisle may prove to be a precious fragment of 13th century workmanship.

The gargoyle at the N.E. angle of this aisle and the scratch dials built into the buttresses of the east end of the chancel, appear also to be relics of the Church of that period. Within the Church, in the gallery window a small fragment of mediaeval glass speaks of art treasures which have been lost.

By means of early wills we can get glimpses of the ancient Church, and a complete search of these documents may add other detailed information. Chancel, nave, and aisles are mentioned as places where burial is requested. One wishes to be buried before the rood, making it plain that the chancel was screened off by rich woodwork which supported the crucifix; another desires to be laid before the figure of Our Lady in the south aisle, where doubtless, there was a side altar. A labourer wishes to be buried near the font on the south side of the Church.

No hint of any external feature is given until the Commissioners of Church Goods in 1553 mention the steeple—a term used alike for tower, spire, and turret. The indefiniteness of this term is removed by Chapman who marks the churches on his map with definite signs indicating whether they had tower, spire, or bell turret. He definitely marks Tollerton Church as possessing a tower. Throsby a few years later confirms this, by his description “It is dove-house topped,” by which he means a gabled tower. Hearne’s picture of the Hall shows us the Church tower before it was rebuilt. Unfortunately Throsby’s vague description of the exterior tells us nothing of its features: “the Church has but an indifferent appearance without.” To our regret, he has nothing to say about the interior as it appeared before the destructive work began, which effaced almost every feature of interest within the Church.

About the time when Throsby spoke of the “indifferent appearance without,” the rector was, deploring the fact that his relative at the Hall was spending an enormous sum of money on the enlargement of his house while the Church was becoming ruinous. Time had evidently left its traces, and the bad custom of burying within the walls of the Church had wrought woeful mischief. The delay in doing necessary repairs finally led to a condition of decay which proved to be fatal to the old Church.

In 1812 the Barrys—to give them their new name—embarked on a scheme of rebuilding. The tower was razed, the roof removed, and some of the walling pulled down. The interior was swept bare of all its fittings. The rebuilding was done in a style which beggars, description, and the result was a hotchpotch of brick, stone, and stucco. Money, which might have been spent on the Church and its furniture, was squandered on a poorly designed tower which was supposed to have a resemblance to that of Magdalen College at Oxford. A gallery pew for the Hall was erected on the outside of the old west wall above two small vestries and the entrance to the Church, and a mausoleum was added outside the south side of the chancel for the burial of the Barrys. A further provision for the family needs was an ambulatory which connected the Hall and mausoleum, an addition against which the rector raised a vigorous but vain protest.

In place of the old interior arrangements, the Church was fitted after the manner of a college chapel, the north aisle being raised on three steps and the south on two steps above the nave. Instead of the old oak benches the Church was newly seated with what a parishioner describes as “garden seats.” Lewis’s (Top. Survey) comment is that the interior is “peculiarly neat though not pewed.”

This destructive reconstruction is reputed to have cost £3,000, of which sum Mr. Barry found the greater part. The churchwarden’s accounts shew that the parish contributed £65 for plastering, and £24 14s. for joiners’ work.

It is possible that, as the aisle windows are poor copies of Early English windows, so the round arch of the chancel was an attempt to reproduce a Norman arch.

For the time being the chancel escaped the destroyer. It had always been the duty of the rectors to maintain this in good repair, and this had been done. One of Mr. Pare’s notes shews that shortly before his death he had repaired the chancel.

“1631—My chancel wall was built or repayred, and finished by Burd and Smith, October ye first.”

What he did, other rectors were required to do. In spite of this, the chancel needed some repair; and when the Rev. Pendock Neale died, and a more pliable rector was appointed, Mr. Pendock Barry Barry completed what he and his father had begun. Dr. J. C. Cox says that “the chancel, of which a course or two above the old foundations remain, followed exactly the old lines.” If this is true of the foundations, it is certainly not true of the walls, windows, and roof.

The rebuilding of the chancel was followed by the reseating of the whole Church with deal pews. The whole of the furniture, altar, pulpit, reading desk, and pews was painted a yellow-drab picked out with black. The principal pews had crestings of iron rails. Dr. Cox, after his visit, remarks, “the whole has a most dreary appearance.”

In 1909 Mr. William Elliott Burnside, who had recently bought the estate, restored the interior, and greatly improved the appearance of the Church. Unfortunately the old capitals of the pillars were now replaced by new work, and these clear evidences of the 13th century church were lost.

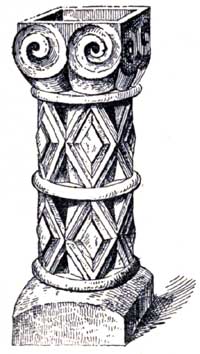

The Piscina.

Norman piscina.

The oldest and most interesting detail of the Church is the piscina. This sole surviving fragment of the Norman period is dated by Dr. Cox as, approximately, cir. 1100. This may be too early, but it cannot be of later work than 1200. It appears to be of a similar date to the piscina at Oxton, to which it has a marked likeness.

The weather-worn appearance of this relic gives us a hint of its chequered career, to which allusion is made in the Gentleman's Magazine for 1848, by Mr. J. Adey Repton, who writes, “In looking over some papers I find a sketch (made thirty years ago) of a curious Norman pedestal of a piscina. It was found among some rubbish in Tollerton Church near Nottingham. A Norman piscina is very seldom to be met with; and I believe the pedestals are particularly rare, for as they project beyond the face of the wall they are generally cut away.”

The date here given corresponds with that of the rebuilding of the Church, and this must be accounted one of the vandalisms of that time.

Even after this note was made, the piscina was removed and set up as an ornament near the arbour at the South Lodge, where it was found by Mr. Welby, the rector. Through his instrumentality it was brought back to the Church, and placed in the west portico. At a later time it was replaced in its old position in the sanctuary.

The Font.

At the time of the restoration of 1812 the ancient font was ejected, and a small pedestal basin put in its place. The bowl of the old font was further desecrated by being put to profane uses. It was discovered in 1918 doing duty as a trough to the parish pump.

The basin font which replaced that of the 13th century was in turn ejected in 1909, and a new font erected. This opportunity or replacing the original font was missed through lack of knowledge of its existence. The base of the Barry font was transferred to the Hall gardens, and crowned with a sundial which tells the passing hours; and the bowl, after vicissitudes, has once more found a place in the Church.

The Bells.

In the inventory of September 4th, 1552 (6 Edw. vi) the Commissioners enumerated among the properties of the parish church,

“One hand bell

iii belles.”

The hand bell which was for use in the sanctuary was confiscated, but on May 26th, 1553 the Commissioners delivered to the rector and churchwardens for their safe keeping the

“iii belles of one accorde henging in the steple of the same Churche.”

When Stretton visited the Church in 1824 he made the unflattering comment that the bells were “of no importance,” and passed them by without a detailed description.

A writer in The Reliquary of 1873 described the bells (somewhat inaccurately), which were still three in number:—

"Treble has the same legend and date as on the tenor at Edwalton, God save the Church. 1634.

Second has George Oldfield’s mark of the same character as the one at Hucknall Torkard—God save the Church. 1640.

Tenor—God save his Church. I. Barlow. I. Pacei. Wardens. 1723.”

It will be seen from the dates that the bells of the time of Edw. VI were recast in regular order from the least to the greatest, and that the old anxiety for the welfare of the Church in the troubled days of Charles I was felt and expressed under the first ruler of the House of Hanover.

Godfrey examined the bells in 1907 and corrected the writer to The Reliquary. He gives the inscription of the second bell, “God save his Church" and the initial of the churchwarden Pacei as E.

His measurements are:—First bell, 2ft. 3½in.; Second, 2ft. 6in.; and Tenor, 2ft. 8½in.

The Holy Vessels.

Few parishes have had richer endowments of holy vessels than this. The will of Thomas Wylford, citizen of London, dated 1405, contains this clause:—“I bequeath to the Church of Torlaston in the co. Notyngham where I was born a priest’s vestment of the value of 5 marks and a chalice of the value of 10 marks there to serve and remain as long as they may last, for praying for my soul and the aforesaid souls,” i.e., his father, mother, his wives Christine and Margaret, his sons Thos. and John, his daughters Elizabeth and Cecily, all for whom he was bound, his benefactors, and all the faithful departed.

This large sum of money—about £100 at the present value of money—would provide a magnificent chalice and cover.

We cannot be sure that the holy vessels named in the Inventory of Church Goods in 1552 are to be identified with the Wylford gift, but this is highly probable. They are described thus: —

“fyrst a chalis of parsel gylt wt. a patend.”

“Parsel gylt”1 means that the vessels were gilt on such parts as are embossed.

In Elizabeth’s reign most of the old and small chalices were recast with additional metal, to give them greater capacity for the communion of the people. If care was taken to return to each parish its own silver, it is possible that Tollerton still possesses in its Elizabethan chalice and paten-cover, some portion of Thomas Wylford’s splendid gift.

This silver-gilt chalice and cover has been the subject of much speculation. Godfrey wrote, in 1907, “the old silver-gilt cup, probably a Grindal cup, has been carefully repaired but the stamps are effaced.” This vessel fell on evil days soon after this time, for in 1918 the stem of the chalice was found to be broken at the knop, and the button of the cover was detached. In 1923 the chalice and paten were sent to Messrs. Comyns and Sons, of London, for repair. Godfrey’s theory of the Grindal cup was rejected by these experts, who expressed a very different judgment on the past repairs. Their report is:—“This chalice is undoubtedly of the period 1560-1570, the evidence which goes to prove this being its shape, the small amount left of the original hall-mark, and the faint Elizabethan engraving still to be seen. This chalice has fallen into evil hands about 50 or 60 years ago; the wires were added on the body and the rim for strengthening purposes (entirely unnecessary). It is impossible ever to restore the chalice to what it was originally.”

The following measurements were given in an accompanying chart: —

A. Cup—Metal, silver gilt; weight, 7 oz. 10 dwt.; height, 7ins.; diameter of top 4 ins.; diameter of base, 39/16 ins.; date letter, circa 1560; marks, indistinct.

B. Paten (cover to cup) Metal, silver gilt; weight 2 oz 9 dwt; height 111/10 in.; diameter of top, 4 ins.; diameter of base, 19/16 in.; date letter, circa 1560.

This chalice was restored to use on Easter Day, 1923.

The rest of the church plate was correctly described by Godfrey:—“Two handsome silver-gilt flagons, two silver-gilt chalices, a silver-gilt paten, and a silver-gilt almsdish. The first flagon, with handle and thumb-rest but without a spout is 3½ inches wide at the lip, and 7 inches in diameter at the foot. It is 12 inches high, weighs 48 ounces avoirdupois and is inscribed “The gift of John Neal, Esqr., to the Parish Church of Tollerton, 1750.”

The marks are (1) the maker’s ![]() 1 on a shield following the shape of the four letters, (2) lion passant, (3) leopard’s head crowned, (3) Roman capital P, the London date-letter for 1730-1. The second flagon corresponds with the first, weighs 46 ounces, and is inscribed “The gift of Pendock Barry, Esq., to the Parish Church of Tollerton, 1812.” The marks are: (1) Maker’s initials H.H. on an oblong shield, (2) lion passant, (3) leopard’s head crowned, (4) Roman capital R, the London date-letter for 1812-13, (5) head of George the Third. The two chalices are the same size as the communion cup previously described. One weighs 8 ounces, the other ounces, and each has the same marks as the second flagon. Each is inscribed “The gift of Barry Barry, Esqr., to the Parish Church of Tollerton, 1813.” The paten measures 7 inches in diameter, is 2½ inches high, and 21/8 inches in diameter at the foot. It weighs 11 ounces avoirdupois, and has the same marks and inscription as the first flagon. The alms dish is 17 inches in diameter and weighs 72 ounces avoirdupois. It has the same marks and inscription as the two chalices.” “Tollerton possesses 203 ounces avoirdupois of silver plate as compared with the modest 15 ounces at Bingham.”

1 on a shield following the shape of the four letters, (2) lion passant, (3) leopard’s head crowned, (3) Roman capital P, the London date-letter for 1730-1. The second flagon corresponds with the first, weighs 46 ounces, and is inscribed “The gift of Pendock Barry, Esq., to the Parish Church of Tollerton, 1812.” The marks are: (1) Maker’s initials H.H. on an oblong shield, (2) lion passant, (3) leopard’s head crowned, (4) Roman capital R, the London date-letter for 1812-13, (5) head of George the Third. The two chalices are the same size as the communion cup previously described. One weighs 8 ounces, the other ounces, and each has the same marks as the second flagon. Each is inscribed “The gift of Barry Barry, Esqr., to the Parish Church of Tollerton, 1813.” The paten measures 7 inches in diameter, is 2½ inches high, and 21/8 inches in diameter at the foot. It weighs 11 ounces avoirdupois, and has the same marks and inscription as the first flagon. The alms dish is 17 inches in diameter and weighs 72 ounces avoirdupois. It has the same marks and inscription as the two chalices.” “Tollerton possesses 203 ounces avoirdupois of silver plate as compared with the modest 15 ounces at Bingham.”

In 1924 Mrs. Welby, the widow of the Rev. A. A. Welby, a former rector of Tollerton, gave to the Church two silver-gilt cups engraved with the Barry arms. At the rector’s suggestion the gift was transferred to the Bishop of Southwell for Nottinghamshire churches needing such a gift. One has suitably been bestowed on the Bishop’s Chapel at Southwell, and the other on a new colliery village.

It seemed doubtful at the time if these handsome cups had been put to sacred uses. They were given to Mr. Welby as a personal gift by Mrs. Susanna Davies in memory of his godfather Mr. Pendock Barry Barry, to whom they belonged.

Mr. W. W. Otter-Barry has recently communicated the interesting information that three silver-gilt goblets were scheduled in the list of heir-looms which passed to his father, but one only came into his possession. The two supposed chalices are doubtless the missing goblets.

The Parish Registers.

The earlier parish registers of Tollerton consist of four volumes. The first volume commences:—“The Regester booke contayning the names of all that have ben crestened maryed and buryed sence the yere of our Lorde 1558 and the first yere of the Raygne of Elizabeth . . after vewd over by John Pare mr of artes and p’son of Tollerton and waranted.” It consists of 32 parchment leaves in a parchment cover and contains entries of baptisms from 1558 to 1728, and of marriages and burials from 1559 to 1728. The second volume consists of 17 leaves of parchment bound in rough calf, and contains entries of baptisms and burials from 1728 to 1790 and marriages from 1728 to 1754. The third volume is a folio book of paper containing marriages from 1754 to 1812. The fourth volume consists of 17 leaves of parchment (ten of which are blank) and contains entries of baptisms and burials from 1791 to 1812, and a Terrier of the Glebe, etc., of the rectory of Tollerton in 1817.”3

There is a gap in the first volume from 1650—1660 when the intruded minister Daniel Chadwicke was incumbent. The registers are in good condition, and but few entries are illegible. With the exception of the references of John Pare and Latimer Crosse to building operations, in vol. 1, and the notes by Job Falkner on the fly leaf of vol. 2, the registers have no special interest.

Among the interesting entries are the following: —

1664—“Mr. Constent . . . was buried the 29th of January.”

1685—“Elizabeth Smith was buryed according to the late Act of Parliament” i.e. in woollen.

1685—“Mr. Willyam Richmond, Regester” buried.

Among the marriages of this period are those of

“Caleb Wilkinson and Dorothy Buckley both of Nottingham, January 20th, 1685-6.”

“Richard Griffin of Nottingham and Mrs. Mary Wells of Thrusington, September 14th, 1686.”

“Thos. Parsons and Catherine Thorpe both of Mansfield Woodhouse, January 19th, 1712.”

The last of these who were wedded here came from the estate of the Squire, John Neale, and their marriage at Tollerton may be accounted for; but the others appear to be examples of the many clandestine marriages which led to Lord Hardwick’s Marriage Act of 1753.

1708—Mr. Richd. Wright of Nottingham was buryed June 22. Among the interesting notes by Mr. Job Falkner, the rector, on the flyleaf of the register are these :—

“In ye year 1745 the Scotch Rebels came as far as Derby with ye young Pretender at yre Head and were defeated att Culloden in April 1746 by ye Duke of Cumberland.”

“In ye year 1749 two Earthquakes were felt at London.”

1757—“Richard Wilkinson Register buried Aug. 14.”

1777—“John Hooley schoolmaster buried March 20th.”

The Churchwardens Accounts.

The oldest Churchwardens Accounts, together with those of the constables, are lost. This loss may be dated about a hundred years ago when many “old papers,” as the informant described them, were burnt on the occasion of the removal of a family who had served the parish for generations, to a new house. There are a few interesting entries in the later accounts: —

| 1789— | Two bell ropes 3s. 6d. | |

| Pd the ringers (Christmas) 1s. | ||

| A Almanack 7d. | ||

| 4 payments Bread and Wine of 4s. each (speaking of quarterly communion). | ||

| Mr. Neale for writing the Regestor 2s. 6d. | ||

| Rent of Wm. Thurman £2 10s. 0d. (probably rent of church land). | ||

| Recd. of Rd. Cooper £1 0s. 0d. (perhaps the rent of the churchwardens cottage). | ||

| 1790— | For holley for the Church (Dec. 25) (?) 1s. | |

| Brieves 6s. | ||

| A labourer one day 1s. | ||

| 1791— | Good Friday. Bread and Wine 4s. | |

| Sunday after Easter. Bread and Wine 4s. | ||

| 1792— | Confirmation 10s. | |

| 1793— | A new seerplis £3 7s. l0d. | |

| 1794— | Leading roof, to plumber Mr. Severn his bill £10 13s. 9d. | |

| 1801— | Pd. at Confirmation £2 5s. 6d. | |

| 1809— | New surplice £2 18s. 6d. | |

| 1812— | Pd. to Brady plasterer £65 0s. 0d. (period of rebuilding). | |

| 1813— | Pd. for iron chest £4 14s. 6d. (the chest built in vestry wall). | |

| Joiners bill £24 14s. 0d. | ||

| 1830— | Pd. for a Praver 1s. 6d. |

The loss of the older records deprives us of much that would be interesting, and not least, their receipts for and expenditure of moneys upon the fabric of the Church. Some little light on receipts for the building or maintenance of the services can be derived from early wills. Until a little later than the Reformation it was customary to leave something in money or kind to the Church. Here are some examples from Tollerton wills : —

Hugh Martell, the rector, bequeathed in 1442 a breviary and 40s. (the equivalent at least of £25) to the Church.

Robert Lovett, husbandman, left “To the Hie Altar iiis. iiiid. in 1529.”

Edmund Farnworthe, husbandman, gave at his death in 1540 “half a quarter of barlie.”

“John Berrey (Barry) Esqr.” by his will, 1545, left “To the Highe Alter of the Church of Torlaston xiis.” and also “my chief rent until the time my heire be married.”

Peter Wilson, labourer, left 3s. 4d. for the maintenance of the Church in 1549.

In 1579 William Grayson, husbandman, left “to the repair of the Church xxd.”

The Churchyard

Throsby described the village and its Church as alike small. We may wonder that he did not comment on the remarkably small churchyard. It is possible that at that time it was considerably larger. By a series of encroachments the churchyard has shrunk to its present proportions. John Duke, a son of an old Hall servant, left this written statement: “When the present Hall was erected a part of the south churchyard was taken for the outbuildings. I have heard my father say that the servants hall, the bottle rack and the brewhouse were built on what was a part of the ancient churchyard.” This statement finds support in the sworn evidence of Mr. Wright of Nottingham in the Barry v. Butlin trial, who said that Mr. Neale “enlarged his servants hall out of the churchyard, and in progress of his work exposed some coffins or bones, which greatly vexed the rector, Pendock Neale.” Further confirmation seems to be derived from an old estate map made for the purposes of a sale of the property in the last century. This is coloured except in some six or seven plots which include the rectory grounds and the Church Close. The uncoloured plots seem to be indicative of lands for which there is no title; and it is significant that the triangular plot bounded by the churchyard, the rectory garden, and the stable drive of the Hall is uncoloured.

A similar encroachment was made on the eastern side of the north portion of the churchyard. In former days there was a low boundary wall here between the Hall grounds and the churchyard. This was removed by the squire, and a fence erected within the churchyard. A protest by the rector led to the removal of the fence further east, and eventually to the erection of the high wall.4 It was held that this wall was built on consecrated ground, and received the name the Dubious Wall, a name which still clings to it.

When the Hall drive was diverted, its old course alongside the rectory was added to the churchyard, perhaps by way of partial atonement. This strip was never consecrated. Two boundary stones were set up to mark the line of division between glebe and churchyard, engraved on the one face, Glebe, and on the other, Churchyard. These stones were thoughtlessly removed and used as steps to the rectory summerhouse. The boundary is more or less recoverable by the line of the rectory paddock hedge.

The gravedigger may some day be astonished to find at the N.E. corner of the churchyard, near the Dubious Wall, a deposit of human bones The history of this deposit was told by Mr. Bernard Ward, to whom they owe their present resting place. When the Barry tomb was made in the south aisle many human remains were unearthed, and were transferred to the middle of the nave. A few years later when a heating apparatus was placed in this part of the nave, these bones with others were again unearthed, and thrown in a heap near where they now lie. Two schoolboys, of whom Bernard Ward was one, struck with the unseemliness of exposure, made a shallow grave; and the bones of old village worthies were reverently buried.

A curious lozenge-shaped stone is built into a central pillar of the south boundary wall, thus inscribed: “H.E., 55 July 1st, 1810.” The register gives no clue to the identity of H.E., and the stone may be a bricklayer’s memorial to himself. The date corresponds with that of the encroachment upon the churchyard.

In the middle of the 19th century a fine row of acacia trees bordered the path to the Church, relics of the old Hall drive; and two large walnut trees graced the churchyard, one on the north side, and the other at the western boundary against the vicarage garden. Oddy5 says that it was by no means uncommon in former days to find walnut trees in churchyards, and names Old Clee in Lincolnshire as an example. Whether these were in any way symbolic or planted for pleasure and profit is unknown. A curious story is told by St. Wulfstan’s6 biographer that the good bishop on going to dedicate a church at Langene on Severn ordered a nut tree which overshadowed the building to be cut down. The patron of the church protested on the ground that he sometimes feasted or played at dice beneath its shade. It is not quite plain if this tree was within the bounds of the churchyard.

The north side of Tollerton Churchyard was not used for burials, save of the unbaptised, until late in the 19th century, when the diminished burial ground made necessity conquer prejudice against north side burials.

In the graveyard are memorials to Paceys, Wilds, Baldocks, Dodsons, Barlows and other old Tollerton families. There is a large cenotaph at the south-east end of the chancel intended for a manorial family, but unused.

1. Shakespeare. Hen. iv, Act 2, Scene 1.

2. “This mark first entered at Goldsmith’s Hall in 1727 by Thomas Cooke and Richard Gurney of ye Golden Cup in Foster Lane, and afterwards used by Richard Gurney & Co.”

3. * Godfrey’s “Churches of Notts.”

4. Hearne’s picture shows neither fence nor wall.

5. “Church and Manor.”

6. Ob. 1095.