< Previous | Contents | Next >

THE VILLAGE OF TOLLERTON.

THE VILLAGE NAME.

There are two villages bearing the name Tollerton, one in Yorkshire and the other in Nottinghamshire. Although the modern spelling is identical, the names of these villages have different derivations, as may be seen by comparing the older forms of the name.

The Yorkshire Tollerton is on the old North Eastern Railway main line, a few miles North of York, and at the extreme northern limit of the old Forest of Galtres. An ancient trackway from Northallerton and beyond entered the forest at this place, and travellers in mediaeval times used to hire fully-armed guides here, to pilot them in safety from robbers to the city of York. The place was regarded as a toll town; and, we are given to understand, thus gained its name. The early spelling of 972, Toletun, and the popular pronunciation give support to this derivation of the name. It became Tolerton, a form still existing in a family name, and finally Tollerton.

The Nottinghamshire Tollerton gained its name in a more devious way. We, unfortunately, have no earlier form of the name than that of the Domesday Book in 1086. It is evident that the Norman scribe failed to catch the true sounds, and wrote it down Troclaveston. He appears to have changed the order of the O and R, misplaced the guttural of the middle syllable, and misrepresented it by C. In spite of his blunders the scribe has left us a hint, in the genitive form ES, that the name of a person is incorporated in the village name. The better forms met with in the 12th and 13th centuries help us to trace the name of the founder of this village settlement. In the Pipe Rolls of 1166 we find the form Turlaueston, and at a similar date in the Lenton Register we have Torlavistune, while Abp. Gray’s Register of 1231 gives the guttural form Torlagheston. These seem to point to a personal name Torlagh, or, as some think, Thorlaf or Thurlac. The final syllable “ton” represents the old English tun, a farmstead, and so we get the meaning, Torlagh’s or Thorlaf’s farmstead.

The developments and variations of the name are full of interest. In the 13th century an h often appears after the initial T, as Thortloneto, Thorlaston, Thorlaveston, Thurlakis-TON, and Thorleston. After that century the h is rare, although we find it as late as the time of Elizabeth in Thorlaston, and the unique Thorloveton. The early forms with u disappear after the 13th century, the last being Thurlakiston. This k form, and the variant c and x forms seem to be confined to the 13th and 14th centuries when we have Torlacton, Torlachton and Torlax- ton. The use of the spelling Torlachton in a Plea of 1335 was made the subject of a legal quibble, and led to a non-suit. On a re-hearing of the case “ the Jurors say that the aforesaid town of Torlachton is enough known by Torlachton and Torlaton and Torlaston.” This disputed form had clearly become archaic in the 14th century.

The process of contraction and simplification will be seen in the following table : —

| Turlaveston | ... ... ... | 1166 |

| Torlaviston | ... ... ... | 1189 |

| Torlagheston | ... ... ... | 1231 |

| Torlaston | ... ... ... | 1284 |

| Torlaton | ... ... ... | 1316 |

| Torleton | ... ... ... | 1428 |

| Tollerton | ... ... ... | 1546 |

| Tollarton | ... ... ... | 1573 |

The modern and final spelling has gone far away from the original form.

THE FIRST SETTLEMENT.

In the field known as the Moat Close, which lies between the village and the brook on the North of the Cotgrave Lane, there is a large enclosure, deeply entrenched, containing an area of about four acres. In the N.E. corner of this enclosure there is a small enclosure containing about half an acre of land. It is a reasonable conjecture that we have here the tun of the first settler, be he Englishman or Norseman, for the tuns of these peoples were often made on low-lying ground near to a stream.

If this is the explanation of this very interesting site, we shall have in the small enclosure, the ground where was the simple dwelling of the settler, and in the great enclosure, the protected fold yard for his cattle, with bothies for the use of retainers.

There are some who see in this moated ground a possible Roman camp. They claim that the Romans, like the later invaders, chose level ground near to streams for their camps, especially when these streams were near the greater rivers of which they were tributaries. In addition to these requisites, the Romans looked for proximity to one of their own roads, or the old roads of the land. This site certainly fulfils these conditions : the brook flows by the enclosure ; the Trent is but three miles away. Although it is not so obvious that the road conditions were met, this was in fact the case. Not only was there the Fosse Way two miles distant, but there passed by this place an ancient road or trackway which linked the Vale of Belvoir with the Trent near to Nottingham. This passed from Kinoulton to the N.W. of Clipston, and passing by the moated enclosure followed the course of the bridle road to Edwalton and beyond. The Clipston portion of this old road is still known as Hereway (perhaps meaning the Army Way, referring to the Danish invasion), or Herewell Lane, but the section between Tollerton and Clipston was destroyed at the Enclosure in 1804.

It must be left to the excavator to furnish conclusive evidence as to the date and character of this enclosure. There are considerations which weigh in favour of the later date for the earth-works; and for their domestic, rather than military character. The names of some of the adjacent fields indicate clearly that one of the old halls stood near to the Moat Close, and tradition tells of a house in that close in the first half of the seventeenth century. If there was a house there at that time, it may well be that it was the successor of older houses built there in previous centuries.

If we are unable to say that there were inhabitants within the bounds of Tollerton earlier than the 8th or 9th century, we have a hint of people who were living near by many centuries before that time. The brook is marked on the Ordnance Survey maps as Thurbeck River. This is an example of reduplication of names which is quite common. When beck was becoming obsolete, river was added; just as in remote times beck had been added because thur had lost its meaning. Thur appears to be a word of Celtic origin, and so bears its witness to the presence in this neighbourhood of a Celtic people. Sanderson’s map gives the name Thurbeck to the northern branch of the stream, and Torr River to the main stream; but the Chartulary of Blythe gives proof that the main stream was known as Thyrbek in the 11th century. Sanderson errs, this time with Chapman (Map 1771) in marking two greater streams. They evidently mistook the diverted channel of the brook for a second stream, and connected a syke with its old course. There is no support for the name Torr River, and it must be regarded as a variant of Thurbeck River.

THE GROWTH OF THE VILLAGE.

If further evidence is needed for the opinion that the enclosure locates the first settlement, it can be found in the development of the village. There can be no doubt that the cross roads near to this moated enclosure became the centre of parish life. Here were grouped in close proximity the village green, the cross, the pinfold, the stocks, and the parish pump. Here too the fair was held, at the parish wakes. The dwellings of the people appear to have been, with few exceptions, built at this northern end of the village. The oldest semblance of a plan which we have met with is that of Chapman’s map, and this shews that the houses were then grouped around the cross roads. The plan attached to the Award is unfortunately lost, but the Report of the Barry v. Butlin Trial contains a plan which we may accept as reliable. The main feature of this plan is the large number of houses in the area between Basingfield Farm and the old smithy. In this space thirteen blocks of houses are shewn. One of the witnesses at the Trial said that one row contained nine or ten small houses, so that there must have been altogether about twenty-five or thirty dwellings grouped together in this central area.

This grouping of the dwellings at the North end of the village raises an interesting question. How did it come about that the village as a whole was detached from the Church, Manor House, and Rectory, which formed a group at the South end of the village? If we could rely on a tradition which claims that the church once stood on a different site, we have a sufficient answer. We have evidence that there was formerly a manor house at the North end, and it would be in accordance with custom that a church should be adjacent to the house of the manor lord. It is just possible that the Kirk Close next to the Moat Close marks the site of an old church.

If there is any truth in this tradition, it carries us back to very early times; for there has been a church on the present site since the 13th century at the latest. It appears evident also that Hall and Parsonage have stood for centuries past, hard by this church.

THE GREEN.

We cannot claim direct evidence for a village green, but there are considerations which strongly favour the contention that there was such an open space at Tollerton. The curious line of the wall of the Hall spinney which skirts the village street, and bounds the farm and cottage gardens, is remarkable. This clearly indicates some ancient boundary, which we assume to be that of the Green.

The old witness who spoke of the row of houses where he lived, which stood within this area, described them as parish houses—i.e., houses on the waste—for which an acknowledgment of one shilling was yearly paid at the Court of the Lord of the Manor, Earlier references to houses occupied by parish officials indicate that these stood on the Common.

It is peculiarly interesting and suggestive that in the sales of the estate in the nineteenth century, this portion of land within the curved boundary wall was marked as carrying the manorial rights. This seems to be a definite indication that it was formerly the Common or the village green, over which the lord had claim as unenclosed land, commonly known as the Waste.

THE VILLAGE CROSS.

The published lists of villages which formerly had crosses omit this village. This is not to be wondered at, for no visible sign of a cross appears, and no tradition lingers. The evidence that there was a cross in the middle of the 18th century is quite clear, and it is reasonable to think that it was not completely destroyed until much later. On the flyleaf of the parish register, among a series of interesting notes made by the rector, the Rev. Job Falkner, is this, “In ye year 1749 I planted ye Elm Tree at ye Cross.” That is clear enough proof that there was a cross. Where did it stand? The answer seems to be, that it was at the old cross roads, in the N.E. angle between the roads to Gamston and Cotgrave. There is to-day at this place, now enclosed within iron railings, a flat- topped mound, and quite near to it the stump of a very old tree which may be that of Mr. Falkner’s tree, perhaps felled when the present plantation was made.

If a proposal to place the war memorial cross on this site had been accepted, the spade would probably have turned conjecture into assurance. It is possible that some of the stones which support the iron fence are fragments of the cross or its base.

THE PINFOLD.

Village pinfolds will soon be numbered among the things that have passed away. There are still many survivors; but few, if any, are put to better use than as a receptacle for rammel and rubbish. This village still has its pinfold, which has occupied its present sheltered site opposite to Chesnut Farm for more than a century. An older brick fold stood on the opposite side of the road, and was removed when the road to Cotgrave was diverted at the time of the Enclosure in 1804. Among the curious subjects brought to light in the Barry v. Butlin trial was the rebuilding of the pinfold. The sole reason for the mention of the matter was that the old squire, who bore the cost of the new pinfold, gave the workmen such liberal potions that a drunken orgy at the smithy marked the completion of the new building.

THE STOCKS.

In the old days when by-law was in the hands of the village community, almost every village maintained its stocks, and very often also its cuckstool. There is no tradition that Tollerton had its cuckstool, but with the brook so handy it is not unlikely that this provision was made for the village scolds. The stocks stood near the new pinfold to the north of the cross roads. It is possible that they as well as the pinfold were removed from the east to the west side of the road, but we have no evidence of this removal. Time out of mind they were just to the south of the present pinfold; and if this was the original position, the curious spectacle must sometimes have been presented of man and beast facing each other in durance vile.

The last recorded use of the stocks was about the year 1845, when a drunken man was pinioned there until he recovered sobriety. Long after this, the stocks remained on the site, bearing their witness to the rough discipline of the days past.

THE MILLS.

The Domesday Survey mentions two mills in this parish. It is said that the mills of the Survey were usually water mills. Tollerton offers equal facilities for wind and water mills, having high ground close to the village, and a brook almost as near. If we regard the general rule as applicable here, we shall expect to find the sites of the watermills near the weirs which are mentioned in the maps of the Ordnance Survey. It is not unlikely that one mill stood near the present outflow of the lake, or possibly where the existing weir dams the brook close to the road bridge, a little lower down the stream. On the west of the stream there is visible an old channel which may have been a mill race; although, with as much likelihood, it may have been the feeder of the moat a few yards away.

The most northerly weir of the O.S. map may seem remote, but there is good evidence that there was a mill near to it. A little distance away are two fields bearing the name Mill Wong which clearly point to a mill in the neighbourhood. Such a mill stood in the Hallbriggfield, which is near by, in 1683. In a document of that date, mention is made of a windmill in an enclosure measuring 33 yards N. to S. and 30 yards E. to W. within Hallbriggfield. A windmill on such low ground is so unusual that we may regard this as the later representation of the water mill of 1086. It is even possible that the diversion of the brook at this point had some relation to the working of the old mill.

In later days, if not contemporary with the mill of 1683, there were two other mills, one on the extreme S.W. of the parish and the other near the village. Among the field names of Russell’s Farm we have Upper and Nether Mill Close. Although there is no other evidence, these names indicate that a mill stood on this high ground above the farm house, near to the spinney planted on Far Mill Close. The other mill, which was situated south of the Bridle Road to Edwalton, where the footpath to that village enters the fields, survived until recent times. Chapman’s map marks it, but places it wrongly on the north of the road. Mill Close definitely locates it, and the old enclosure around it is still visible. Throsby’s picture of Tollerton Hall shews this fine brick mill with its graceful dome as it appeared about 1790.

The family of Hickling worked this mill for some generations. In 1810 the miller carelessly threw down a match after lighting his pipe, and the mill was burnt. So passed the last of the Tollerton mills.

It is interesting to note that in the will of Hugh Martell, a rector of the 15th century,, he bequeathed his mill horse with its gear to a relative. The privilege of milling was the exclusive right of lords of the manor with the exception of the parson, and we thus learn that some Tollerton parsons, at least were independent of the lord’s mill.

THE VILLAGE INN.

It is through a horrible tragedy recorded in the Coroner’s Rolls that we are made aware that in far back times this village had an inn. The Roll of 1350 briefly tells the story of a fratricide in the village inn.

“The townships of Torlaston, Cotegrave, Basynfeld cum B(oy)ton and Gamelston in Adbolton present that at Torlaston in the twilight of the Sunday next after the feast of St. Andrew 23 Edw. iii a certain Henry le Schaloner and William his brother were sitting in the tavern of John at the Church and strove between them concerning the chastising of Robert their brother so that the said William moved with anger struck the said Henry with a certain knife to the heart, whereof he straightway died, the value of the knife one penny. He had no goods, lands or tenements. And Alice his mother first found him and is attached by the pledges of Andrew Fox and Richard Heryng.”

The natural conclusion from the name “John at the Church” is that this tavern was at the church end; and, according to common custom, near to the Church. There is a tradition that there was once an inn near the Basingfield Farm, and this fairly meets the expression “at the church,” especially if we can place it in the paddock to the south of this farm house.

We hear again of the inn early in the 17th century in connection with an Admiralty case. A young Tollerton farmer who was under examination at the Admiralty Court incidentally speaks of the visit of certain persons concerned with the case to “an alehouse in Torleston nere my father’s house.” This farmhouse may possibly be that of the tradition. If so, it was replaced by the present building a century or more ago.

In “A Particular Account of all the Inns, Ale-houses, etc., in England with their Stable room and Bedding in the year 1686” the Nottinghamshire Return* includes this village, the name being given in a remarkable form,

“Tolleeton. Guest beds 1, Stabling for horses 2.”

This is the last reference to the inn which we have met with. If we may believe village tales, a second inn was added at some time after this return was made. There is no evidence in support of this, and it is more likely that the one village inn was closed before many years had passed.

A nineteenth century application for a license was refused.

THE MANOR HOUSES OR HALLS.

Soon after the time of the Norman Survey, the manor was divided, and two lords continued for centuries to hold the one knights fee. Two manors almost of necessity imply that there were two manor houses, halls, or chief messuages as they are variously called. There is sufficient evidence to enable us to be sure that there were two houses, and to locate them with some measure of accuracy; one to the north of the village, and the other to the south.

Pendock paid Hearth Tax on fourteen chimneys. This big house was without doubt on the new site, for Dr. Deering in his History of Nottingham, 1751, remarks that the Hall “a pleasant house” had been “of late very much altered and improved by John Neale, Esq., who at present lives in it.” How long Philip Pendock’s Hall had stood there cannot be determined. It may have been since the early Tudor period.

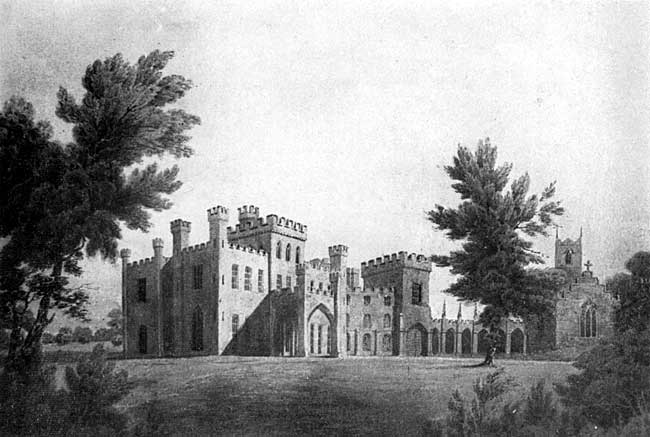

Tollerton Hall as sketched by John Throsby c.1792.

The Hall which Deering mentions was soon “very much altered "by John Neale’s grandson, Pendock Neale. The sketch given by Throsby shews us an unattractive four-storied building with two low wings. Pendock Neale retained the central block and built around it on the north, east, and west, and crowned the whole with turreted chimneys, the roof being screened by battlements. The surface of this brick building was dressed with stucco, the work of Italians brought over for the purpose.

A quaint result of this blending of the old and new was that many of the old rooms were left in total darkness.

This creation of Pendock Neale has been described by Godfrey as “one of a class of buildings with sham turrets and impossible battlements, which Pugin scathingly denounced.”1

TOLLERTON HALL

From the Picture by Thomas Hearne.

A water colour drawing of the Hall, made in 1787 by the artist Thomas Hearne, F.S.A., hangs in the Castle Museum at Nottingham. It was bequeathed to the city by Mr. W. S. Ward, a son of a former rector of Tollerton.

THE PARSONAGE.

The present parsonage or rectory is that which Latimer Crosse, the rector, built at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century. By means of this rector’s note in the parish register, we can date the building exactly, for he tells us that it was begun in 1697 and completed in 1702. “Mr. Latimer Crosse, Rector, rebuilt the Parsonage House, Anno 1697 the West End and the East End 1702.” This typical Queen Anne house was planned on the lines of a widespread H, with one central room, and two rooms in each wing. A beautiful feature of the interior is the chesnut staircase, the design and workmanship being alike good. It has suffered much from neglect, and has been overlaid with paint, but is worth careful restoration.

The exterior, with the exception of the room in the middle of the south front, is as it was in the builder’s time. Mr. Barry added this room with two lean-to bedrooms about 1840, after the parsonage had narrowly escaped destruction by fire. The bedrooms were removed in 1918, and the windows of the old central bedroom were replaced.

Latimer Crosse’s house was the successor of that which had been almost entirely rebuilt about a century earlier by the rector, John Pare. Like his successor, John Pare recorded his building operations in the parish register. These are his notes :—

| 1611— | “Made my best (? east) chamber and ye 2 little chambers. Burde.” |

| 1618— | “My hall taken down and built up, tyled, and plasterd and rough cast. Trowel, Burd.” |

| 1619— | “Ye west end of hous set straight, wald, rugh cast and plaster flord with a new oven and a lead2 all which I made and repayrd this year. Trowel, Burd.” |

| 1627— | “My chambers towards ye well was all new latted and new thacked.” |

This house which Mr. Pare restored may have been that which is mentioned in the time of Henry VIII—1535-6—as part of the parson’s possessions. We get some idea of the dimensions of this, house from the assessment for Hearth Tax in 1674, when the parson, John Allsopp, paid tax on seven hearths.

There is no direct mention of the parsonage house earlier than the time of Henry VIII, but the will of Hugh Martel, 1442, with its references to goods and chattels, and horse, will necessarily imply that there was a house for the parson at that time. Indeed we may take it for granted that from the time when the Church was built or even earlier, there was a parsonage or priest’s house hereabouts.

From very early times until less than a century ago there was. a full equipment of farm buildings attached to the parsonage. Hugh Martel in the 15th century had his mill, and of course his tythe-barn for the corn which fed his mill. He would necessarily have his stables and cowsheds.

John Pare’s building notes cover a whole range of farm buildings.

| 1604— | "Built my p’sonadg kiln and cowhouses new. T. Trowel.” |

| 1608— | "Built my great barn this year. T. Trowel.” |

| 1610— | "Built my p’sonadg hay barn this year. Blagg.” |

| 1625— | "My tyth barn was built in my fowld yard syd and finishd Nov. ye fifth. Blagg.” |

| 1634- | "My malt howse was repayred and set straight and 3 new garners made April 8th.” |

In this long record of building and repair no mention is made of the dovecot. The oldest portion of the dovecot, which collapsed in 1928, may have belonged to the early seventeenth century. It stood at the S.E. corner of the old fold yard. It was not until the middle of the 18th century, when Mr. Ward became rector, that the fold yard was divided by the wall running north and south, and the eastern portion was converted into a pleasure garden.

During excavations in 1918 for the purpose of laying a drain, foundations were cut through on the north of the N.E. room indicating that an older parsonage extended to the north of the present building. About the same time other less substantial foundations were unearthed between the Rectory and the Churchyard.

1. Notts. Churches, Hundred of Bingham.

2. The “lead” was a leaden vessel or boiler for brewing.