< Previous | Contents | Next >

A Story of the Plague

HOLME. Strange things have happened in this pleasant village of orchards and farms, which found itself at the end of the 16th century on the east bank of the Trent instead of the west, owing to the river having changed its course in a great flood. The plague came this way in 1666 and frightened an old woman into a queer hiding-place; and there is a tradition that Dick Turpin used to visit a cottage here, stopping to give Black Bess a drink on his famous ride to York.

Between the road and the river is Holme Old Hall, a creepered farmhouse with mullioned windows which has grown from the house where centuries ago the Bartons lived. With part of the fortune he made out of wool in the Calais trade John Barton rebuilt most of the church where he has been sleeping since 1491, and it is said that he put in a window of his house the words:

I thanke God, and ever shall,

It is the shepe hath payed for all.

One of his descendants married the Royalist brother of Lord Bellasis (who was Governor of Newark at the time of its surrender), and their son married Cromwell's daughter Mary. Lord Bellasis lived either at the Old Hall or in a house which stood where the red brick Holme Hall stands now.

Holme church in 2003.

After years of neglect, the wise restoration begun in 1932 by Mr Nevil Truman is bringing back the charm of the church John Barton left. It is one of the few complete Tudor church interiors, with all the fittings put here in 1485. With walls aslant, gabled red roofs, and big tilting 15th century windows letting in a blaze of light, it has something to show of all the building centuries from the 12th to the 15th. Below the east window inside are two fragments of Norman stringcourse. There is much 13th century masonry in the north wall and at the east end, and in the north doorway hangs the ancient door with its old bar fastening. The tower with its short sturdy spire and grinning gargoyles is 14th century, with buttresses and a west window a century younger. In the little gallery of sculpture on the hoods of the windows are quaint heads, angels with shields, and the laughing face of a man in a postman's hat. Over a window is a charming spray of a rose and leaves, and on a parapet is a grotesque with a human head and an animal's body.

The handsome two-storeyed porch is part of John Barton's rebuilding, which included the addition of the south aisle and the chantry chapel. Over the entrance is a fine band of seven shields, carved with heraldry, the initials of the Bartons and their badge of bears and tuns, the merchant's mark, with bales of wool, and the Staple of Calais with sheep below. Two gargoyles show a man with a book and a staff, and a grotesque struggling with a dragon.

The tragedy of a poor old woman clings to the upper room of the porch, known as Nanny Scott's Chamber, for it was here she fled (with food enough to last some weeks) when the plague was in the neighbourhood. From the window she would see a lovely view of the river close by, and the green fields and trees towards Newark, but the sight that arrested her old eyes, was of her friends being carried, one by one, to their last rest. When hunger forced her to leave her refuge she found only one other left alive in the village, and, horror-stricken, she returned to this room and never left it till she died.

The nave arcade and the two bays between the chancel and the Barton chapel divide the interior of the church. The great east window of the chancel glows red, gold, blue, and brown with a fine medley of old glass. John Barton's memorial glass in the three middle lights shows initials, heraldry, bears and tuns, parts of big figures of saints, and small groups of women; the glass in the two outer lights belonged to Annesley's old church, now in ruins; it includes the Coronation of Our Lady (1363) and shields of arms.

The chapel has a handsome canopied niche on each side of the east window, and a lovely piscina niche with the drain cut in the middle of a flower. The massive benches and stalls are original, though very worn, with poppyheads of angels, birds, dogs, lions, and grotesques. Enclosing the chapel from the aisle and from part of the chancel is 15th century screenwork, and more of it divides the chancel from the nave, there being no chancel arch. Holding up the arch between the chapel and the aisle are two stone heads, one with bared teeth, one scowling; and a dragon and an angel support old brackets. The medieval stone altar has been set up for use in the chapel.

The benches are for the most part as in John Barton's day. The altar rails are 17th century. There is a battered old chest, and the tower screen has been made up of old panelling from another church. A pair of plain iron standard candlesticks is from the 15th century. There is a Queen Anne chandelier. A plain cross in the church was made from the lead which secured the shaft to the base of the old village cross, a fragment of which still stands by the wayside, where a grassy lane goes down to the ferry. The shaft and base were parted early this century in a vain search for a record of the age of the cross.

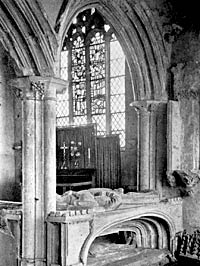

The Barton tomb, c.1930.

On a great stone tomb between the chancel and the chapel lies the church's benefactor, John Barton, with his wife; his feet are on a tun with a bar across the top, and hers are on a dog with a collar. John wears a long belted gown, Isabella a long-sleeved gown with cuffs and an ornamented waist-belt, her banded headdress falling in folds behind. Below the table of the tomb lies a shrivelled corpse on a sheet, a grim spectacle. In his will (the original of which is at Nottingham Castle) John Barton directed that his body should be buried "in my new tomb in the chapel newly constructed by me."

There is no memorial to Charles Stuart's General, Lord Bellasis, but a floorstone is quaintly inscribed:

Here lies interred the Bodys of John Belasys of Holme

in the County of Nottingham Esq: and of Cathrine

his wife. Catherine Dyed in 1716 and Mr Belasye 1717.