< Previous | Contents | Next >

The Crown of Thorns

Headon church in 2014.

© Copyright J.Hannan-Briggs and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

HEADON. It has a fine view-point at its little church, where for 600 years two stone faces have been looking out from the tower on a patchwork of fields and woodland. An unusually spacious tower, it looks almost as wide as it is high; it is thought that its builders meant it to be higher and perhaps to have a spire, and that the Black Death stopped the work, except for the addition of the embattled parapet. It has tiny lancets and a 14th century west window, and inside, with 17th century altar rails across its arch, it is a charming setting for the modern font mounted high on three steps, its bowl resting on a wreath of water lilies. From the 15th century come most of the windows and the arcades, their end arches on old and new brackets and fine heads of women and bearded men. The lovely Jacobean pulpit, with two grotesque figures supporting a canopy, is daintily carved with arcading. An old chest has six carved bosses which seem to be from the old roof, and there is a splendid dug-out chest shaped from the trunk of a giant oak, its wood seven inches thick in parts, the old hinges and hasps fixed on to a new lid.

At the foot of an oak crucifix hangs a small crown of thorns which were gathered near the spot where the Judgment Hall stood in Jerusalem when Christ was tried before Pilate. This crown must be very like the one He wore.

Sir Hardolph Wasteneys, the last male of his line, died in 1742 and has an inscription here. Headon had belonged to them from the 14th century, and Sir Hardolph rebuilt the old home, little dreaming that it would be pulled down before his century was done. Some of their trees live on, and one of seven fine avenues which used to radiate toward the hall is still here, over a mile from the village, where the road to Grove cuts through its splendid limes and chestnuts.

From a Saxon Tomb

Hickling church, c.1900.

HICKLING. On the edge of the Vale of Belvoir, sheltered by the Wolds, lies this border village where the basin of the canal, much beloved of fishermen, comes to the road. There are magnificent views of the wide green vale from the top of the rough road going south, and from the massive tower of the church standing in a square of fine trees. It has rare things in its keeping.

The tower has been rebuilt from its 14th century material, and a newel stair climbs from a small medieval doorway to the parapet, passing the works of the clock in a glass case. The chancel has been made new, but its arch, like most of the old work in the church, is 600 years old. The clerestory is 15th century.

The walls and arcades are leaning, and the tinted stone is charming against the plaster indoors. There is old timber in the roofs of the nave and aisles, and fragments of old glass are in a medley of new in the east window. A pillar almsbox is 1686, the font with angels under its bowl is about 1400, and three bench-ends of the same time have quaint heads on the arms and in the poppyheads.

One of the fine possessions here is the 14th century oak door letting us in, patterned all over with the delicate scrolls and leaves of the original iron hinges which have a charming lace-like effect. On the floor of the chancel is the brass portrait of a priest holding a chalice, one of only two priest brasses in the county. An inscription which seems to be upside down (for the head of the brass is toward the east instead of the west) asks us to pray for the soul of Master Ralph Babington of 1521, a rector here whose small figure we remember on his father's tomb in Ashover church, Derbyshire.

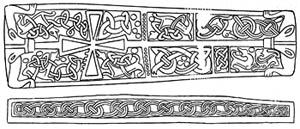

Anglo-saxon grave cover, Hickling.

The oldest treasure, and one of the finest things of its kind in the land, is a relic of a thousand-year-old tomb, the coped cover of a Saxon coffin. It is 5 feet 6 inches long, showing in its mass of carving a fine cross, and animals enmeshed in interlacing knotwork. An animal at one end is biting its own tail. Very beautiful is a 600-year-old gravestone built into an outside wall, carved in relief with graceful branches of leaves growing from the stem and head of a cross. Some of the 18th century slate stones in the churchyard are remarkable for the fine lettering of their inscriptions.

Hockerton church, c.1905.

HOCKERTON. This plain little village, with Southwell for a neighbour, has two things left of Norman days, both in the church which stands by two old yews. One is the chancel arch, the other a small window in the nave, its deep splay making a fine frame for a bright modern St George. There is a 13th century lancet in the same wall, and most of the other windows are 14th century.

The low embattled tower is 500 years old. The unusual font, with eight sides and a round rim, may be 700 years old. The old stoup is in the porch, a tiny old almsbox is set on a new pillar, and one of the bench-ends has been here since 1599. Pleasing for its glass and for its story is a window showing St Nicholas, the Madonna and Child, and St Cecilia with her organ. The face of Nicholas is that of a gracious old man, James Fuller Humfrys Mills, a much-loved rector who ministered here for 56 years. He came just before the Crimean War and died two years before the Great War.