< Previous | Contents | Next >

He Led the King to the Scaffold

EAST BRIDGFORD. This charming old village, full of story, stands high on a wooded cliff overhanging fine reaches of the Trent. The main road has passed it by since the coming of the new bridge at Gunthorpe, but its delightful green lane still drops sharply down to where the old toll bridge spanned the river. In a field by the church is a windmill without sails; at Newton near by is another with no sails, a fine old giant and a landmark for many miles. It is said to have been one of the string of windmills which stood on the ridge overlooking the Forest at Nottingham.

The oldest story of the village is being revealed in our own time by the excavation of Margidunum between the village and Bingham—one of the line of Roman forts built along the Fosse Way, Britain's straightest road. Over twenty years of patient digging and research by Dr Felix Oswald have brought to fight many relics now housed at Nottingham's University College, indicating the importance of the site in the Stone and Bronze Ages.

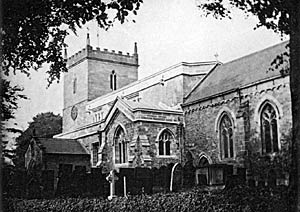

East Bridgford church, c.1914.

The next step in the story is the church, which is old enough to have been burned by the Danes. The Civil War touched the village very closely; in a skirmish here Colonel Ferninando (son of the Earl of Chesterfield) was killed, a year before his gallant brother fell in the storming of Shelford House near by; and it still has a house where lived a man who listened to some of Charles Stuart's last words.

For the Old Hall of mellowed brick, at the end of a rose-bordered drive not far from the church, was the home of the Hackers, and is little altered (except for additions) since their day. Here about 1590 came to live John Hacker, a rich man and the head of a family who were all Royalists but one. The Roundhead member of the family was Francis Hacker, who married Isabella Brunts of East Bridgford; there is in this church a memorial to her father Gabriel Brunts. Hacker was a firm supporter of the Parliament. A fine soldier, he is reported to have given all the prizes he took to the State and to his men, and the king is said to have offered him the command of a choice regiment of horse if he would serve him. He remained faithful to his cause, however, and at the trial was one of the officers charged with the custody of the king, escorting him daily to and from Westminster Hall. The king's death-warrant was addressed to him and two others.

Thomas Herbert, the faithful servant of the king, who lay at his bedside on his last night, tells us that Colonel Hacker wished to place two musketeers in the king's bedchamber, at the thought of which the king gave a sigh, but the bishop and Mr Herbert, resenting the barbarousness of such an act, never left the colonel till he withdrew these men. The next morning, Thomas Herbert tells us, Colonel Hacker knocked at the chamber door, and Mr Herbert would not stir to ask who it was, but at a second knocking the king bade him go to the door, and the colonel said he would speak with the king. The king said, Let him come in. The colonel in trembling manner came near and told his Majesty it was time to go to Whitehall. The king bade him go forth: he would go presently. They walked through the park and the king arrived and went to his bedchamber, where after some time Colonel Hacker attended at the chamber door, and the king took notice of it saying, Open the door, and bade Hacker go and he would follow:

A guard was made all along the galleries and the banqueting hall, but behind the soldiers abundance of men and women crowded in to behold the saddest sight England ever saw, and as his Majesty passed by with a cheerful look he heard them pray for him, the soldiers not rebuking any of them.

It was this East Bridgford boy who led this sad procession to the scaffold, and who later was to be led to the scaffold himself, for after the Restoration his name was on the list of those who were to die for having encompassed the death of the king. It transpired that the death-warrant of the king was in Hacker's house, and his wife was sent to fetch it. She delivered it in the hope that it would save him, as proving that he acted only as a soldier under orders; but nothing could save him, and he was hanged on October 19, 1660, his body being given to his friends for burial, and laid in the church of St Nicholas Cole Abbey, London.

Although a number of the Hackers lie in East Bridgford church, their only monument is to John, the first to live here. He kneels with his wife at a desk, with four sons and two daughters below them. He died in 1616, the date of the monument being wrong. The eldest of the sons was father of Francis; he died in 1646 and sleeps here with his wife. Two brothers of Francis who sleep here are Thomas (killed in a skirmish at Colston Bassett when Francis was fighting on the other side) and Rowland, who lost his right arm defending Newark and lived till 1674. After Francis Hacker's death, Rowland was allowed to buy back most of the family estates.

The battered stone figure of a cross-legged knight, wearing chain-mail with surcoat and shield, was found in the garden of East Bridgford Hall; he may be Sir John Caltoft, a medieval lord of part of the manor. On the wall above the recess in which the figure lies are the arms of John Babington of 1409, owner of a small estate here. His son William was Chief Justice and Baron of the Exchequer.

In the wise restoration of the church early this century 12 feet of Saxon walling 34 inches thick was found below the chancel floor, with other stonework which showed that the chancel of the church that came into Domesday Book was only eight feet wide. Traces of fire here led to the belief that the ancient building had been burned by the Danes. Two fragments of a Saxon cross, and a 13th century headstone (buried in an upright position in the churchyard) were found at the same time, and are in the church for us to see. The chancel was rebuilt on a bigger scale about 1200, and was given its charming priest's doorway later in the 13th century. The middle portion of its 14th century arch is nearly a thousand years old; the 14th century sedilia and piscina were restored after being found in the rector's garden. A fine roof with angels at the ends of the beams looks down on the nave with 14th century arcades and a clerestory of the 15th. The porch with gargoyles and. a niche with a modern figure, and some tiles with many patterns, are also 14th century. The tower was rebuilt in 1778.

Here Were the Romans

EXCAVATIONS at East Bridgford have brought to light the Roman Posting Station Margidunum established beside the Fosse Way, the great road constructed by the conquerors of Britain from Exeter to Lincoln, the straightest road in our country.

But before this place became a posting station it was a Roman Camp, perhaps one of the forts referred to by Tacitus as erected on this side of the Severn and the Trent for keeping the enemy in check. Margidunum appears to have been established about the middle of the first century, during the invasion by the legions of the Emperor Claudius, and the excavations by Dr Felix Oswald have confirmed this view.

Oak planks from well at Margidunum, c.1926.

Arrowheads of the Bronze Age have proved that the site is an ancient one, obviously chosen for its easy defence, having marshes on two sides and good drinking water twelve feet down. The Roman legionaries at once sank wells, and one of the most remarkable discoveries made by Dr Oswald is the oldest of all on the site, a well lined with a square casing of oak planks. It is clear that when this lining of oak had been placed in position clay was rammed round it, and the oak has been wonderfully preserved; we may see it with the other relics of the station at University College, Nottingham. After about 19 centuries they still show marks of the workman's tools.

The age of the pottery found in the well indicated that it had been filled in about the time of Boadicea's rebellion, when Margidunum was abandoned and burnt by the British.

The Romans returned to the camp and lived in it for another fifty years, when, not requiring it for military purposes, they appear to have razed it to the ground. The foundations of the walls they built, of stone-lined wells and cellars, and a great number of pots of various shapes and sizes, have been dug up. Many potter's marks have been deciphered by Dr Oswald, who is famous for having printed with his own hands, page by page, an authoritative book on this subject. The task he set himself was nothing less than the collecting of about 20,000 stamps of Roman potters, arranging them alphabetically, and recording the shapes of some of the vessels on which they occur; and when this vast index was ready, and was found too great an undertaking for a publisher, Dr Oswald set it up in type himself.

Face pots.

When Margidunum became a posting station the Fosse Way was reconstructed straight through the old camp, and by the time of the Emperor Constantine it had become a flourishing little place, judging from the things discovered there—urns with moulded human faces, the Samian bowls, and other pottery of the period found here. In the year 367 the Picts and Scots swept through Britain, and the concrete foundation and part of the stone rampart built at this time to defend Margidunum has been revealed. Close up to this wall (which was probably 18 feet high) the remains of a building set up on the site of a former bath-house have been found, the floors composed of pink concrete on which lay fragments of wall plaster decorated with bands of red, orange, and green. There were thick roofing slates, which are known from the positions of the nail-holes to have been arranged in diamond pattern, and on the floor of one room was a newly-minted coin of the Emperor Valens.

Among other objects found by Dr Oswald on this interesting site were bronze ornaments, an iron sword, a gridiron, a bucket handle, a spring lock, some keys, a bronze pin with a head like an outstretched hand, and an enamelled seal-box of native British workmanship. Altogether Margidunum, though covering about seven acres, has revealed much of the life and history of this county during the Roman occupation of Britain.