< Previous | Contents | Next >

A Fine Sweep of the Trent

Dunham-on-Trent church, c.1910.

DUNHAM. Its medieval tower calls us from afar and arrests us when we reach it. Keeping company with slender firs, it is a charming picture from the road beyond the gay flower garden of a cottage, or through the old stone archway opening to the churchyard, its great capitals carved with grotesque animals and foliage.

The tower is a noble tribute to the builders of the 15th century, and finds its glory in windows remarkable for their size and beauty. Four transomed windows light the upper storey, filling the walls to such an extent that from a distance the top of the tower seems almost detached from the rest. Another splendid window is over the west doorway, and between them is a small canopied niche. Its lofty archway, reaching to the roof of the nave, is as wide as the tower itself, and has foliage capitals. This ancient tower is all that is left of an old church twice rebuilt last century, and it was sad to find it calling for help with the pathetic appeal, "It is unsafe, so that we dare not ring the bells."

There is good carving of last century in the shallow sedilia, adorned with four-leaved flowers, and in the piscina with a band of ballflowers.

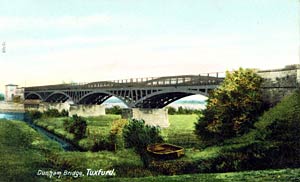

Dunham Bridge, c.1910.

The village is neat and trim, delightfully set on the bank of the Trent. An ugly toll bridge which carries the road across to Lincolnshire has the saving grace of being a fine place from which to see a lovely panorama of our green and pleasant land, with the river sweeping grandly to flow in fine reaches to Laneham. We see Laneham church on one hand, and on the other Fledborough with its church and its countless string of arches over river and bank; across the river is North Clifton's church in Notts and that of Newton in Lincolnshire. The wooden stakes of the ferry can still be seen near the bridge. It was at this spot that a duke and his retinue met William of Orange to escort him to Welbeck.

The Village Afraid of a Hero

EAKRING. With red-roofed houses lining the road, and fine views of the Forest countryside, it is the resting-place of a hero whose story lives undying in the annals of human courage. Yet Eakring was afraid of him and kept him from them, like a leper in a hut.

Eakring church in 2000.

At the foot of the village, by the rectory, stands the church, much restored and made new. The tower has a 15th century top storey on a 13th century base which has a carved stone over its doorway showing traces of a figure. The sides of the tower arch are perhaps Norman, and there are three 13th century lancets in the chancel. There is a fine little Jacobean pulpit with a canopy, a poor-box of 1718, a small old chest, and a 17th century font like a pillar. The arms of Charles the Second are in the church, and in the porch are those of Elizabeth, brought from a house in the village which was once an inn where the queen is said to have stayed. Two stone corbels on an outside wall show a woman's worn face and a demon with bared teeth.

William Mompesson.

A brass plate tells us of George Lawson who gave the church a silver chalice; he was rector here before the coming of a new rector who was told that he must not enter the village. He was William Mompesson, who from September of 1665 to October 1666 had laboured in plague-stricken Eyam, ministering to his pitiful flock as they awaited their dread fate and perished one by one, till less than 40 of Eyam's 350 folk were left alive.

Three years had passed since the plague when he came to Eakring, but the people were afraid of infection, and Mompesson had to live for a time in a hut in Rufford Park. It is one of the saddest examples we have come upon of the superstition of country folk. He remained at Eakring for 38 years and died in 1708. On the chancel wall is the brass plate which used to be in the floor over his grave, and a modern inscription tells of his ministry at Eyam. The poor glass in three lancets is his memorial.

The scenes through which this devoted man and his wife chose to live were almost too appalling for description. It was difficult to bury the victims, for no one dared to touch them and there was no possibility of making coffins for them all. One wife and mother buried her husband, and six children in eight days.

Perhaps the story of this brave rector comes nearest our hearts as we stand in the fields with only the sky above us, where a simple rustic stone cross marks the spot at which he used to preach during his pathetic exile from the village. Near the cross is a young ash tree which has replaced the old one under which he used to stand. It was known as Pulpit Ash, and was destroyed by lightning some time ago.

From this rough cross, which stands at the head of a field at the top of the village', we have a pretty view of Eakring among the trees, and a fine one of the countryside.