< Previous | Contents | Next >

Underneath Byron’s coffin (left) may be seen that of the “Wicked Lord” which is on the crushed leaden shell of the fourth Lord Byron. The coffin under that of Lady Lovelace (centre) is the coffin of Byron’s Mother.

The leaden shell (right) rests on eight inches of debris.

There were others present in the Church to whom reference is made in the foreword. Whilst they were inspecting the Vault, the Antiquary, the Surveyor, the Mason and I withdrew to the Church Hall, where we found opportunity to compare notes. For some time previous to the opening of the Vault we had discussed the possibility of its being an ancient crypt which the Byrons of the seventeenth century requisitioned as a burying place. Some old inhabitants of the town who had claimed to have seen it when Lady Lovelace was buried in 1852, declared that it had a vaulted roof, and that they remembered seeing three or four arches. This information encouraged us to hope that we might make an interesting archaeological discovery. Alas! our hopes had been dashed to the ground. We all realised that, as we sat talking over the evening’s experience. But what of the size of the Vault? We were disappointed, and not a little puzzled by its small dimensions. Had we only opened part of the Vault? Was there any possibility of its extending into the Chancel?

It is commonly reported locally that an old parish clerk named John Brown used to lower a candle into the Vault through a hole which he had made, and allow visitors for a small charge to look at the coffins below. It is not known exactly where this hole was, but it is said to have been in close proximity to the Byron tablet in the floor. This story gave support to our conjecture that another portion of the Vault might be beneath the Chancel northwards, and in consequence arrangements were made for a further work of excavation on June 22.

Plans had been made to close the Vault during the night, but the brickwork under the Chancel steps had collapsed, and it was found necessary owing to lack of material to delay operations until the morning. The party broke up at midnight, and I went back to the Church for a private inspection of the Vault. I was fortunate in having the assistance of the Photographer, the Caretaker of the Church Hall, and a member of the Church Council. They were keenly interested, and shared my spirit of reverence. When I reached the floor of the Vault I found myself standing on several inches of debris, varying in depth, but covering the whole of the floor. On examining the debris I discovered that it consisted of decayed wood, perished lead, and innumerable bones. I knew from a careful study of the registers that at least twenty-seven of the Byron family had been buried in the Vault. What conclusion could I come to but that at my feet lay the bones, and crumbled coffins of the early ancestors of the Poet?

Immediately beneath the bottom step of the staircase, and near to the North Wall of the Vault, I saw a small leaden coffin, lying parallel with the step. It was evidently not in its original position. I examined it very carefully, but I could find no plate upon it by which it might have been identified. It was the coffin of a baby, and may possibly have been that of Ernest, one of the children of the third lord, who died in infancy, and was buried in 1671.

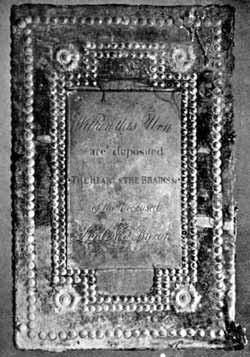

The inscription on the oak chest containing the Urn in which are the heart and brains, etc., of the Poet.

The inscription attached to the lead within which the Urn is encased.

The foot of this small coffin was crushed beneath the weight of a chest, almost a double cube in shape, and covered by the remains of velvet of a faded purple colour, adorned by brass-headed nails, and brass funerary ornaments. The chest stood upright upon its smaller end. There was no difficulty in identifying this with the Urn referred to in the description of the; funeral procession, for on the lid I found a brass plate with the following inscription:—

“Within this Urn

are deposited

the heart and the brain

of the deceased

Lord Noel Byron.”

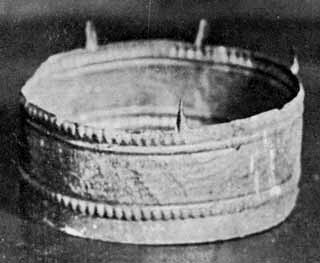

The chest was in a very good state of preservation.. Laying my hand on the lid, I discovered that it was quite loose. I raised it, and saw a closed leaden case, on the top of which, not attached to it in any way, was another brass plate. The inscription upon it was not quite identical with the one found on the wooden chest. It was as follows: —

“Within this Urn

are deposited

the Heart

and the Brains, etc.

of the deceased

Lord Noel Byron.”

I wondered why on both the inscriptions the chest was referred to as an urn, for in appearance it had not the slightest resemblance to one. The only conclusion I could come to was that “the heart and the brains of the deceased Lord Noel Byron” were contained in an urn, and that the urn had been encased in lead before being placed in the chest. Some corroborative evidence of this I have since found in a book published in 1874, called “The Home and Grave of Byron,” by Richard Allen.

I was now able to give my attention to the main part of the Vault. As I stood at the bottom of the staircase, I saw that the coffins which were intact, or partially intact, were arranged in three piles, lying east and west, and were stacked one on the top of another. My first task was to examine the coffins of the first pile, which; were about one foot from the north wall of the Vault.

The uppermost coffin was of striking appearance. It was made of oak, and in a very good state of preservation. Originally it must have been covered with purple-velvet, for fragments of this still remained under the brass-headed nails with which it had been secured. The sides of the coffin were beautifully decorated with numerous funerary ornaments. I was eager to identify this coffin, but alas! the plate on the lid was missing, although the marks where it had been affixed were quite distinct.

There was little doubt in my mind that this was the Poet’s coffin, but with the plate missing I had to seek other evidence.

|

|

| The Coronet on Byron’s Coffin. | The Coronet on the coffin of Augusta Ada, his daughter. |

On the top of the coffin and near the head, there was a coronet. I examined it carefully and was able to identify it as the ordinary coronet of a Baron. It had consisted of a rim with six pearls set directly upon it, and a cap of crimson velvet lined with ermine, and surmounted by a gold tassel. The rim, with four of the six short spikes to which the pearls were attached, was still intact, but the velvet cap, the tassel and the six pearls had disappeared. The velvet cap and tassel may have succumbed to the ravages of time, but souvenir-hunters must have been responsible for the disappearance of the pearls, when the Vault was opened for the burial of Lady Lovelace.

If this coronet were in its original position—and it had every appearance of being so—it confirmed my belief that the uppermost coffin on the north pile was that of the poet.

Upon a closer examination of the coffin I made the discovery that the lid was loose, and not in any part attached to the sides and ends, to which originally it had been nailed. Could the Antiquary have been right in his opinion that the coffin had been opened? I tried to put the thought away from me, but when on raising the lid slightly I saw that the leaden case within had been cut open, I could come to no other conclusion.

Someone had deliberately opened the coffin. A horrible fear came over me that souvenirs might have been taken from within the coffin. The idea was revolting, but I could not dismiss it. Had the body itself been removed? Terrible thought! From time to time visitors to the Church had asserted in my hearing that the body of the Poet was not in the Vault. I wondered now on what ground this assertion could have been made. Had they known of the opening of the coffin, and received some secret information that the body had been removed? The more I thought about it, the more fearful I became of the possibility of the coffin being empty. There was the coffin before me—the lid was loose and easily raised—the leaden case within torn open.

Within the case was another coffin of wood—the lid had never been fastened. What was beneath it? If I raised it, what should I discover? Dare I look within? Yes, the world should know the truth—that the body of the great poet was there—or that the coffin was empty. Reverently, very reverently, I raised the lid, and before my eyes there lay the embalmed body of Byron in as perfect a condition as when it was placed in the coffin one hundred and fourteen years ago. His features and hair easily recognisable from the portraits with which I was so familiar. The serene, almost happy expression on his face made a profound impression upon me. The feet and ankles were uncovered, and I was able to establish the fact that his lameness had been that of his right foot. But enough—I gently lowered the lid of the coffin—and as I did so, breathed a prayer for the peace of his soul.

|

|

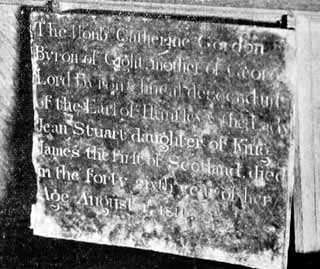

| The inscription on the oak coffin of the Poet’s Mother. | The inscription on the leaden shell within the oak coffin of the Poet’s Mother. |

Looking farther into the Vault I saw, on the top of the poet’s coffin, and leaning against the east wall of the Vault, at an angle of about sixty degrees, an oblong brass plate which was very badly tarnished. I took it in my hands, and read the following inscription: —

“The Honble. Catherine Gordon Byron

of Gight. Mother of George Lord Byron

and Lineal descendant of the

Earl of Huntley and the Lady Jean Stuart

daughter of King James the First

of Scotland, died in the 46th year of her age

August 1, 1811.”

J. Carr, Scr.

Nottingham.

This plate had evidently become detached from the coffin of the poet’s mother, fallen amongst the debris, and placed in the position in which I found it, by one of the workmen who built the east wall of the Vault in 1887.

I next turned my attention to the coffin immediately below that of the poet. The oak sides had perished, and only small pieces of wood remained attached to a leaden shell. I thought at first that this might possibly be the coffin of his mother, but after some little time, and with considerable difficulty, I found upon the top of the shell, in a normal position, a brass plate affixed, by which I was able to identify the coffin as that of the “Wicked Lord.” The inscription on the plate was as follows: —

“William, Lord Byron.

Died, May 21st, 1798.

Aged 75.”

|

|

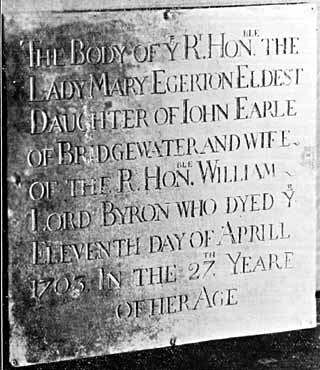

| The coffin plate of Mary Egerton, the first wife of the fourth Lord Byron. She died of smallpox eleven weeks after their marriage. |

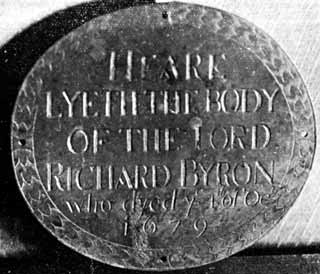

The coffin plate of Richard, the second Lord Byron. |

Moving my hand over the top of the leaden shell, I discovered, towards the foot of it, another brass plate, loose and evidently not in situ. It was the brass plate which had at one time been attached to the coffin of Richard, the 2nd Lord. This, too, had been rescued from the debris and placed where I found it. The inscription on the plate was extraordinarily clear and read as follows: —

Heare

Lyeth the Body

of the Lord

Richard Byron

Who dyed ye 4th of Oct.

1679.

There was yet another plate, of lead and rectangular in shape, "which at some time had been rescued from the debris, and placed on this coffin towards the head. It had originally been affixed to the leaden shell in which was the body of Lady Mary Egerton, the wife of the fourth Lord Byron. It was inscribed as follows: —

The Body of ye Rt. Honble. the

Lady Mary Egerton Eldest

Daughter of John Earle

of Bridgewater and wife

of the Honble. William

Lord Byron who died ye

Eleventh day of Aprill

1703 In the 27th Yeare

of her age.

Underneath the coffin of the “Wicked Lord” and resting on the debris was another leaden shell. The wood which originally surrounded it had entirely perished. The dimensions of the shell were such as to allow of no doubt whatever that it contained the body of a man. It had collapsed under the weight of the coffins above it, and was in a very dilapidated condition. I examined it carefully, and came to the conclusion that it contained the body of William, the fourth Lord, who was buried in 1736.

The three coffins on the north side of the Vault, which were intact or partially intact, were therefore those of the fourth, fifth and sixth Lords. It appeared to me that this space had been reserved for the head of the family in each succeeding generation, and I concluded that the debris on the floor beneath this pile comprised the remains and crumbled coffins of Richard the second Lord, who died in 1679, and William the third Lord, who died in 1695.

I was now able to turn my attention to the coffins in the middle pile. There was no difficulty whatever in identifying the uppermost coffin as that of Augusta Ada, the poet’s daughter. It was on a level with his coffin, and there was a space of about one foot between the two. It was of oak, and in a wonderful state of preservation. At the time when it was placed in the Vault, it had a covering of purple velvet, and this was secured by brassheaded nails. There were fragments of the velvet still remaining, but most of it had perished. The funerary ornaments were in their original position, but I noticed that one or two of them had fallen to the ground. The inscription affixed to the lid of the coffin was very clear, and could be easily read at a distance. It was as follows:

The Right Honble.

Augusta Ada

Wife of

William, Earl of Lovelace

and only daughter of

George Gordon Noel

Lord Byron

Born 10th of Decr.

1815

Died 27th of Novr.

1852.

On the top of the coffin, at the head, a coronet rested. It was in a very much better state of preservation than that of Lady Lovelace’s father. It originally consisted of a rim, on the top of which were eight points of considerable height, each point bearing a pearl, alternating with the pearls was a like number of strawberry leaves on the rim below. Within the coronet there had been a cap of crimson velvet lined with ermine, and surrounded by a gold tassel. On examining the coronet, I found that the crimson velvet and the tassel had perished, but fragments of the ermine remained. The rest of the coronet appeared to be quite intact.

Beneath the coffin of the poet’s daughter, and resting on the debris, there was another, of approximately the same size, but portions of the wood were badly decayed, disclosing a leaden shell. I felt certain that this was the coffin of the poet’s mother, and that the loose brass plate bearing her name, to which I have already referred, had been attached to it.

In my endeavour to identify this coffin I examined some of the funerary ornaments which had fallen to the ground, but they were nothing more than the ordinary decorations of that time. I noticed, however, that the whole of the lid of this coffin had perished, laying bare the top of a leaden case. There was just the possibility of there being another name plate attached to this, and I accordingly looked for one in the normal position. With some difficulty I was able to pass my hand over the top of the shell, and felt what I thought was a leaden plate attached to it. If I were not mistaken, I knew that this would establish the identity of the coffin. I was not disappointed, and after some little time I was able to read the wording on the plate. It was identical with the wording on the plate found at the foot of the poet’s coffin and leaning against the east wall of the Vault, except that there was added to it the name of the engraver—J. Carr, Sct., Nottingham.