< Previous | Contents | Next >

CHAPTER 1.

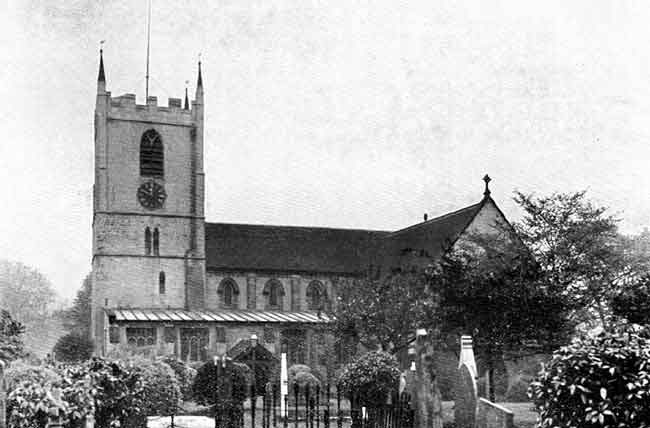

THE CHURCH OF ST. MARY MAGDALENE,

HUCKNALL TORKARD.

The Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Hucknall Torkard. 1938.

In very early times part of the great forest of Sherwood was cleared around the spot where the Parish Church now stands. There is little doubt that the clearing was made in Roman times. Roman coins and tiles have been found in the locality, and there is some slight evidence that there was once a Roman Villa in the vicinity of the present church.

In the early part of the fifth century the Roman legions were withdrawn from Britain to protect their own country against invasion. A few years passed, and Jutes, Angles, and Saxons landed on these shores, and drove the Britons into Cornwall, Wales, and Strathclyde.

The country was divided into seven kingdoms. Over the great Central Kingdom, Mercia, a powerful warlike chieftain named Penda ruled from 614-655 A.D. Towards the end of his reign, so we learn from the early historian, the Venerable Bede, the kingdom of Mercia became the centre of missionary enterprise. Five missionaries—Cedd, Adda, Betti, and Diuma—and later Chad, were sent from Lindisfarne by Bishop Finan, at the request of Peada, King Penda’s son, to evangelise the Mercians. These missionaries penetrated into every part of the kingdom, and in their journeyings visited the village of Hochenale—as its name was then spelt. The high ground on the north of the village green, where the church now stands, would be the spot where the people gathered to receive instruction in the Church’s Faith. Nearby was a running stream, now hidden from sight, but still flowing beneath the main path of the churchyard. Here the first converts would receive the Sacrament of Holy Baptism, a stone cross hallowing the place of their new birth. This spot the Christians would regard as holy ground, and thither they would resort for worship and prayer.

Where was the exact position of this cross ? When, was the first little church built to take its place? Is it possible to answer these questions ? Have we any solid ground upon which we may build up the early history of the church ?

For some years local archaeologists have inclined to the belief that the first little church of the village was built towards the end of the twelfth century. A closer examination, however, of the architectural features of the ancient parts of the building, and extensive excavation work have proved conclusively that there was a church in this village long before the twelfth century. An account of the work that has recently been carried out may be of interest to all those who hold this ancient church in veneration on account of its association with Lord Byron.

In describing this work in the first person the writer desires to associate with himself, Mr. J. Holland Walker the Antiquary, Mr. N. M. Lane the Surveyor, and the brothers Robert and James Bettridge who wielded pick and shovel—all of whose names are mentioned in the Foreword, and without whose help the results could never have been attained.

|

|

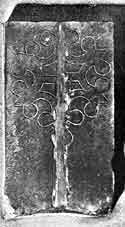

| The Coffin Slab of a Crusader in Hucknall Torkard Church circ. 1200 A.D. | A Coffin Slab with an incised Cross in Hucknall Torkard Church circ. 1140. |

At the time of the last restoration of the church in 1887-1888 two ancient coffin slabs were found under the floor—one, I believe, under the floor of the Chancel, and the other under the floor of the Lady Chapel. These slabs were removed, and are now affixed to the south wall of the south Transept. For some years my attention had been drawn to them, and I endeavoured to assign to them a date. The larger of the two slabs bearing upon it, in relief, a cross of surpassing beauty, and a sword hilt and pommel, I thought must have covered a crusader’s tomb. The smaller one, with an incised cross, appeared to be of earlier date, but was not perhaps of the same interest.

Eight months ago I sent photographs of these two slabs to some eminent authorities. My opinion was confirmed by them all, and one of them gave me additional information of a very interesting character. He asserted that the larger slab was that of a crusader who lived in the reign of Richard the First (1189-1199) and was of noble birth, and that the smaller one was of much earlier date.

This information led me to examine more carefully the architectural features of the lower part of the Tower, and as a result of my examination, I felt convinced that it was of an earlier date than that assigned to it by the local experts.

Upon the suggestion of my friends, Mr. Holland Walker and Mr. Lane, I arranged for some photographs of the Tower to be taken, and submitted to some of the highest antiquarian authorities in the country. They had no hesitation in stating that the Church was of Saxon origin, built under Norman direction. The whole of the masonry of the Tower, up to the belfry stage, they said, was eleventh century work of the “overlap” type, and the unbuttressed angles of the Tower and the quoin work were thoroughly characteristic of an early period.

I was encouraged by this opinion to seek for further evidence of a still earlier church. That there had been one I had no doubt whatever, but I hardly dared hope that I should be fortunate enough to discover its ancient foundations. I decided, however, that it was worth while undertaking a work of exploration.

The old Manor House had stood on the west side of the Tower, and it seemed to me likely that the first little church would be in close proximity to it, and might possibly have been the Manorial chapel. I therefore concluded that if the foundations of this building remained undisturbed, they would be found under the floor of the west end of the Nave.

It took me some considerable time to decide where to commence operations. Pews and floorboards had to be removed, and I naturally did not wish to disturb more of these than was absolutely necessary.

Eventually, my plans were laid for starting excavations on the line of the arcade between the Nave and the north Aisle. The pews and floor boards between the pillars at the west end of the Nave were removed without very much difficulty, and in little more than half an hour I had a working space of six feet by three feet. On the surface there was loose travelled earth, and into this I probed, but could touch nothing solid. My two assistants then proceeded to clear away the loose soil to the depth of about a foot. Probing operations commenced again, and this time I felt something solid six inches beneath the surface. I wondered if my hopes were to be realised. There was no necessity to give instruction to my assistants to work very carefully. They shared my interest, and were as desirous as I was of making a discovery. The soil was moved by handfuls, and very soon a wall was laid bare. I examined it carefully, and finding it to be built of packed rubble, I knew that I had discovered a very ancient foundation—definitely of Saxon construction.

I was naturally desirous of finding out how far this foundation extended in an easterly direction. The pews and floor-boards between the next two pillars were removed, and loose soil to a depth of three feet removed, but I made no further discovery. Either the foundations had been disturbed here, or the eastern wall must have been nearer the Tower. I was determined to continue my investigations.

Returning to the place where I had started operations, I made some calculations, and decided to try and strike the eastern wall in the middle of the Nave on a line north to south about a yard on the west side of the second pillar. This involved the removal of four pews and a long length of floor-board, but my labour was amply rewarded. At the depth of a foot and a half I found the foundations for which I was looking.

I now felt confident that I should find the south wall of this ancient church. Knowing that Saxon buildings never had a roof-span of more than fifteen-and-a-half to sixteen feet, I measured fifteen-and-a-half feet from the north wall along the line of the eastern foundations. Again fortune favoured me, for I struck the south east corner of the ancient building.

It was a wonderful experience. In the course of a few hours I had been able, with my assistants, to carry back the history of the church nearly three-hundred years. The Surveyor inspected the work the following day, confirmed my opinion, and took measurements for the plan, which is reproduced in this book.

There was more work to be done.

If the Tower had been built about 1090 A.D. I concluded that a nave and chancel must have been built at the same time, and that if the foundations of these could be found, their construction would provide additional evidence of an earlier date than that of the twelfth century which had previously been assigned to it. I decided to look for these foundations under the seats in the front part of the Nave.

After an interval of a week the services of my assistants were again in demand, and they prepared a working space on both sides of the Nave in a line with the two arcades.

I started operations in line with the north arcade, but there was no sign whatever of any foundations. It was disappointing. However, before abandoning hope, I decided to try a line about two feet to the south of where I had been working, and in little more than twenty minutes, I was in possession of the evidence that I sought —a foundation of small packed rubble, in coarse lime mortar. As this was out of the line of the arcade, I concluded that I had struck the old Chancel wall, and that the Chancel of this eleventh century church must have been less in width than the nave.

Excavations on the south side of the nave proved equally successful. I discovered foundations of the same construction as those which I had found a short time before, but on this side they were in line with the south arcade. Reference to the excellent plan prepared by the Surveyor will enable the reader to understand the work which I have just described.

There was still more evidence that I required, if it were possible to obtain it—evidence of the date of the north aisle, and the Lady Chapel.

I felt certain that the date assigned to these two parts of the Church—the fourteenth century—was much too late. Accordingly, I first of all examined the bases of the pillars, and formed the opinion that they were definitely early English. The mouldings were characteristic of this period. This opinion was supported by my two friends, Mr. Holland Walker and Mr. Lane. We were all agreed that the arcade was built, and the north aisle added, about 1200 to 1220 A.D.

For some time I had associated the Crusader, the slab of whose tomb I have already referred to, with the building of the Lady Chapel. Many of the Chapels of ancient date were given by crusaders as a thank-offering for a safe return from their perilous expedition, and dedicated to Our Lady. I felt sure, therefore, that we were indebted for the Chapel to the Crusader whose body lies within the Church. If I were right in my conjecture, then the Chapel must have been built about the same time as the north Aisle. Could I find any evidence of this ?

First of all, I examined the bases of the pillars in the arcade between the Chapel and Chancel. Some of the mouldings on the pillars had been badly mutilated, but they provided evidence that the Chapel was built not later than the early part of the thirteenth century. Was this all the evidence available ? Bearing in mind that the Lady Chapel had been moved stone by stone in an easterly direction to allow for the addition of Transepts, I thought that there was just the possibility of the builders providing new foundations and leaving the old ones in their original position. Accordingly, I prepared for a further work of excavation on the site where the north wall of the Chapel stood.

There was no doubt that if the foundations were still there, they would be on the line of the north wall of the aisle. I worked with my assistants very hopefully. Here we had a much larger space in which to operate than we had in the Nave; consequently, we were able to make rapid progress. Within a very short time we came upon the foundations of the original Chapel. They were built of random rubble in lime mortar, with squared bond stones. This was all the evidence I required in support of the Chapel being of earlier date than that previously assigned to it. I had proved to my satisfaction, and to the satisfaction of my friends that the Chapel had been built about 1200-1210 A.D. After making all these most interesting discoveries, I was in a position to reconstruct the history of the Church.

It was probably in the eighth century that the villagers of Hochenale decided to substitute an Altar for the Cross, to which for some fifty or sixty years they had resorted for prayer and worship, and build their first little church. They laid the foundations of packed, rubble, and proceeded to erect upon them walls made of wattles, gathered from the stream nearby, and mud. There was an abundance of timber in the forest, and beams of oak were hewn to span the walls and bear the roof.

When the work of building was completed, arrangements were made for its consecration by the Bishop. It must have been a great day for the people of Hochenale when the Bishop visited the village, and in a simple, but beautiful and dignified service, set apart for the worship of God their first little church, and dedicated it to the honour of “Saint Mary Magdalene and all Saints.”

Here the villagers of two or three generations gathered together frequently to offer at the Altar, which stood on the site of the Cross, their sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving.

It is wonderful that the packed rubble foundations of this first Saxon church still remain, and that they enable us to fix the exact spot, once marked by a cross, where the first missionaries stood to proclaim the good news of the Gospel, and where the first converts were baptised into the Christian Church.

Towards the end of the eighth century, news spread abroad throughout Anglo-Saxon England that the armies of the Danes had landed in the north; that they had sacked Lindisfarne—the great centre of missionary enterprise—and that they were marching inland, demolishing the churches as they went, and putting the Christians to death. It was not long before they invaded Mercia, and during this invasion, it is reasonable to suppose, the church at Hochenale was burnt to the ground.

|

|

|

| St. Mary Magdalene Church, Hucknall Torkard, 1824. | Hucknall Torkard Market Place, 1860. |