The above pages have mainly been devoted to the through passage or traffic of the town from east to west, where its gradual development can be fairly well traced. It is not a line that tells any stories of its ancient agriculture, its meadows, cornfields, woods, wastes, and forest lore—nor do we obtain sight of or touch with the County Gallows within its bounds. Those we must consider as part of a distinct through-passage south to north, in which that great feature, the cliff of the town, played a prominent part. This cliff, like the river Trent, formed a natural bar, hostile or otherwise, to progress from south to north. As before, we cannot give dates, and are barely able to suggest (even when we have proof that one feature is later in sequence than another), the approximate time when these roads came upon the scene; suffice it to say that the two road systems are traceable as separate and distinct factors. As already expressed, I am inclined to give the palm of age to that which offered the least resistance, i.e., that already noted, whose trend was from east to west; but there came a time when obstacles were so far surmounted that a greater south to north road system was established. This greatness is traceable to the physical contour of these islands, unduly long on the latter line. The same fact has influenced our modern railways.

What we must now consider, are two fixed points in the township, the Trent and its ford—improved at an early date into a bridge in the south, and the dominating Gallows-hill on the forest in the north.

The river being crossed, the road to town, half-way across the meadow—"The Rye Hills"—was always dry; the low-lying remainder—"Crofts"—was subject to floods, during which this part of the road was impassable. We have historical evidence of a bridge being thrown across the river Trent in 924. This may not have been the first erected there; and it is questionable whether it was other than of wood or timber, capable of carrying foot-passengers or single-file mounted horsemen. It was the most important bridge across the Trent, and the one —like later the "Bridge of London"—that stood nearest to the sea, all the lower reaches of the stream being un-bridged. Its placc, three centurics later, was occupied by a national one of stone, with pointed arches, part of which remained in use down to our time; and of which one arch Mill remains.

At the foot of the cliff, or town, was another bridge of equal importance, across the river Leen, Thoroton alludes to It an existing in the time of King John; but we have evidence of a stone one, in 1320, of twenty arches being in disrepair, and repairable by the hundreds of the county, Nottingham being considered as one. This was clearly a "County Bridge," and landed between the foot of Malin Hill and Hollow Stone (see the town map given in Dr. Deering's history). It is now but imperfectly known how the ancients surmounted the difficulty of the town-cliff, but it is certain that its presence broke the continuity of the line of road, and drove it westward. Malin Hill and Bellar Gate strike one as the oldest links in this chain; the former, now landing opposite St. Mary's Church, may have done so a little short of that point, and there joined a lost south extension of Stoney Street, now or lately occupied by St. Mary's Vicarage House. Hollow Stone, hewn out of the rock on both sides, presents itself as a later duplicate of this scaling of the rock at Malin Hill: Bellar Gate, stopping short in Barker Gate, the ancient street-line through the earthworks of the town, would give an alternative route to Stoney Street.

This lands us in the heart of the old borough, the highest part of the rock, where we see the natural cliff was its south boundary or defence. [See map-tracing II.]

To grasp this northern highway through the old town, we must consider the bearing of the defensive earthworks upon it. This Stoney Street line was, and still is, the only way through them. The inner line of streets is still fairly intact, and can be perambulated— starting westward from St. Mary's Church we have High Pavement—parallel with the cliff; Old Market Street and Fletcher Gate—parallel with Bridlesmith Gate—the latter in the new borough and outside the old one; Bottle Lane, Warser Gate, and Woolpack Lane—parallel with lost Chandler's Lane, Carlton Street, Goose Gate, and Hockley. On the eastern line, Count Street and Carter Gate—parallel with Sneinton Street and Water Lane. On the cliff top, we have "White Cow Yard" (now a footway), and Short Hill cum Hollow Stone; completing the round. Of Stoney Street, we have record in time of King John, as "The Stan Street of Nottingham." Its northern end was the outlet of the old "burgh," from which point commenced the partly agricultural road along the Beck Valley, later, "St. Anne's Well Road," to the town-woods and wastes and Mapperley Hills, leading towards Lambley, Woodborough, and Calverton. Proceeding northwards, past the top of Goose Gate, the Stan Street line became "Broad Lane," now Broad Street— extending to "York Road," later Glasshouse Street, where in the hollow of the old "Lark Dale" at Burton Leys, it threw off a second agricultural road, which became Charlotte Street (now absorbed in the joint railway station). Its further trend westward is now marked by Shakespeare Street, and away through the cemetery on to the forest waste; still further north, this great streetway, partly disturbed by the joint railway, wended direct to the top of the Gallows Hill. [See map-tracing III.]

Let us now go back to the site of the old Leen Bridge of twenty arches, and we shall see that this great Stan Street line was diverted, or carried westward, to the outside of the earthworks on the hill, and there repeated. This gave the line of Narrow Marsh, Drury Hill, Bridle-smith Gate (the two latter in the new borough), High Street, Clumber Street, and Mansfield Road, to the end of the pronent Woodborough Road, where it joined the older way to the Gallows. This latter way, climbing the somewhat lower cliff at Drury Hill, became the great highway and the industrial line of the medieval town. Such was its state or standard, that, when the two boroughs or towns were walled in as one, in the 13th century, the top of the rock at Drnry Hill became "a Stone Postern"; and one of the Great Gates in the walls—if not the greatest—spanned the north end of Cow Lane, later Clumber Street, as "Cow Lane Bar" or the "North Bar." This route, in the Narrow Marsh and Drury Hill portion, declined, in what we know as the Old Coach Days, when the "Hollow Stone" was taken seriously in hand to admit of the passage of stagecoaches; an undertaking only rendered possible by the rounding off of the corner of Middle Pavement and Bridlesmith Gate—our first street improvements. No one ever heard of coaches passing along the old "Stone Street," and it is doubtful whether its line was ever provided with a gate or postern in the north, or 13th century, town wall. With this western movement of part of the old town—now the covered-in Lace Market and the home of the Mother Church—we trace a minor detail, again of unknown age, though its line furnished the boundary between the old and the new boroughs, towns, or manors, and, in time, of the two parishes—St. Mary's and St. Peter's. It was a footway for those of the south who crossed the Trent Bridge and the "Rye Hills" of the London Road. Its south foot is now marked by the east end of Kirke White Street, and its north end by the foot of Drury Hill; crossing as it did, the low lying part of the great open meadow, it was not passable in time of flood, although it was so to some extent in the 18th century, when it took the form of a raised wooden or plank-causeway.1 It crossed the Leen-water at the south end of Turncalf Alley, now Sussex Street, and as an alley or lane, joined and passed the foot of Drury Hill, to die out in the old week-day marketplace as "Middle Hill" and "Garner's Hill" footways. Viewed from where it crossed the river Leen, with the Trent bridges and town wharf away in the south, its peculiar name, "Turncalf Alley," reads like a corruption, on the tongue of "Townwharf Alley." It is a strange order that this old footway should still be with us. After the construction of the canal, in the closing years of the 18th century, it was preserved by what became known as "The Wooden-bridge," recently replaced by one of iron, and improved into a highway; further south, it is an elevated foot-way over the Midland Station, where it has the appearance of part of that establishment. On crossing that "Wooden Bridge," a branch of it was a trodden path in the open grass to Wilford and its ford and ferry, the Sunday walk of all walks in and about the old town. Its representative, in large part to-day, is the modern Queen's Walk.

Writing these notes, the mental fruit of a long drawn study of the town—beloved of youthful days—is a labour of love; but we have not done, we have not got back to the origin of the town, and what lay hidden by time behind it, when made the Metropolis of a county. Compared with its like in Leicester, Derby, York, and Lincoln, we cannot trace a Roman base or substructure. We must therefore look for an earlier or later date as that of its foundation. We know, in the presence of Southwell, that it was not ecclesiastical; civil it must have been, and that of a defensive character, as proved by its physical features of pronounced hill, valley, water, frowning rock, and sheer precipice. In ownership, we first recognise it as a jewel in the king's crown, with the care and custody of the highroads and waterways of the county attached thereto.

For quickening inspiration about Nottingham in a far away day, let us go to the summit of Derby Road, divest the mind of all buildings, even the high roads, as scars denoting the presence of man, and take in the panorama of the town site, leaving out the county of the town as later accessories won from surrounding wastes. You are there on an elevated site, where, looking east, you have a roughly square area, naturally defended on four sides by great valley or water lines, the spot where you stand resembling a bridge or entrance into an area, one that a few yards rise of water would convert into a peninsula, where now it is only a promontory. Its northern ditch is the vale (with depth diminished and its brow cut down), whose lowest line is marked by Shakespeare Street. The eastern ditch, is the valley and stream of the Beck, which, down to living memory, was flanked, on the Sneinton side, by a sandcliff, in Manver's Street, a north wing of the Hermitage cliff. The south ditch, was the low meadow, backed by the river Trent, where the cliff of the town was a sure defence of itself. The west ditch, was the Park hollow, of its kind a pronounced example.

Those who have seen the well-nigh perfect prehistoric fort, a place of strength or security for men and their belongings when in a rude or tribal state, at "Mark-land Grips," miles west of Creswell-Crags, cannot fail to gauge the physical features of Nottingham, with that example, and noting this difference, that one-fourth the boundary at Markland is artificial, cannot fail to realize that the top of the Derby Road alone—valley to valley— needed a defence to convert the whole natural area into a city of refuge.

We have an historical hint of this in unearthing a large neolithic stone-axe, tool, or weapon of Early-man, whilst excavating the site of the joint railway station—Great Northern and Great Central—in 1883, now stored in the Natural History Museum of the city; and further, in Nottingham Castle, where is stored a find of bronze-socketed celts, great warlike instruments in their day, found immediately outside the above lines (where now we have Great Freeman Street), on October 5th, 1860. This find, Sir John Evans records, in "Ancient Bronze Implements of Great Britain," as "sixteen socketed celts; fragment of a sword; a quadrangular tube; a knife a long ferrule; a palstave, and spear heads,"— twenty-four objects in all.

The influence of the ford and ferry of Wilford, on the street plan of the old town, is but faintly marked, and is confined to the west end or the shadow of the Castle rock. Nothing in the form of a bridge or causeway over the lower parts of the meadow can be traced; the cartways or horse-paths, in my time, were defined by sundry white posts, which served as guides when the floods were out. But Wilford Ferry gave us Lister Gate, the street of the dyers, the lower half of which became "Greyfriars Gate" after those particular friars obtained a footing in the town; and the upper half extended north to the oldest thoroughfare, Pepper Street, there by way of Wheeler Gate obtaining access to the Great or Saturday Market. Wilford Ferry also gave us Finkhill Street and Walnut-tree Lane, which became a deeply cut or worn narrow way, that appears to have extended on under where now is the General Hospital, and then on by the Rope Walk, or town and park boundary, to the top of Derby Road. (See map-tracing IV.)

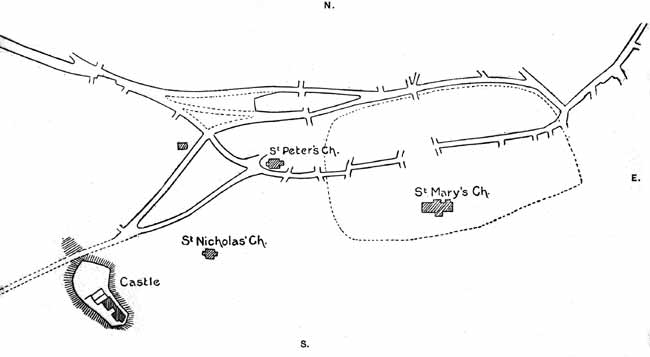

Map I.

Map-tracing of Roads through Nottingham, East to West.

Tracing No. I. shows the area of the old Burh in dotted lines, with what remains of the time-worn, but now deserted way E. to W. through it. It shows the position of the three churches, St. Mary's, a pre-Norman foundation in the King's great manor— St. Peter's, and St. Nicholas' Churches, mentioned in the foundation deed of Lenton Priory (1103-1108) as then established; and what is viewed as the earlier "Earl's chapel," that later became the "White Friary," now an uninhabited stone building in Friar Yard, Friar Lane. The development of the northern or "Long Row" line created a waste lying between it and the central "South Parade and Poultry" line, and forming the area described as "leg of mutton "shape of the present Great Marketplace. The position of the Castle is shown in the S.W. on a neighbouring hill. (Page 54 above.)

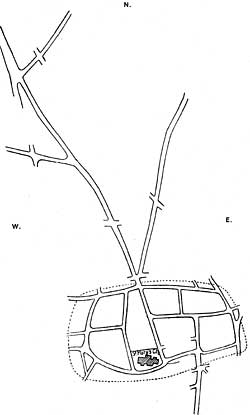

Map II.

Map-tracing of Nottingham Old Borough.

Tracing No. II. is interesting, as it shows the "old Burh" and its "lay-out" of streets, or ways—which still remain unchanged—and serve for what is now known as "The Lace Market" (the south dotted line is the precipice), its northern outlet, and the roads used or developed by the early occupants in cultivating their extensive town or cornlands; that trending N.N.E. from the outlet of the Burh, aimed for the valley of the Beck-stream, the Holy-well of St. Anne, the town woods, and stone quarries, the "High-Plains," and by highway on to Lambley, &c.; that trending N.W. is the great highway of the "Stan Street" of King John's time and before, alias the York road or street; its off-shoot to the west traversed the old Lark-Dale—the valley of "Shakespear Street" to-day— and so led to the western half of the open forest land of the town; all which were embraced under the specific term of "The Sand Field," as all on the E. side of the "great-way" was known as "The Clayfield." The further off-shoot trending N.E. led to and stopped short in the old "Snapedale," now traversed by "Great Alfred Street North"; its fountain in the "Trough close," gave it the later variant of "Plague-dale." This old north district of the town-lands had been one long marked out for isolating the plague-stricken of the townspeople, while those of the county were housed in many rock-holes about the foot of the Castle rock. The old road leading into "Snapedale" as "Fox lane," disappeared, with the enclosure of the open town-lands in the middle of the last century. It is now the lower part of Woodborough Road, which is carried forward as a tram-line over the old "Toad-hole hills" [Tod=a fox] to Mapperley Plains—the highest lands of the old township. (Page 60 above.)

(1) "South View of Nottingham, from the Rye Hills, 1741,"— reproduced by Job Bradshaw in 1841.