A crosslet, about 2in. in size, has been cut on the internal wall at the western side of the south doorway. It is inconspicuous and may have to be diligently searched for, but it is unmistakably there. Another crosslet, equally difficult to discern, is on the second jambstone at the west side of the easternmost window in the north wall of the chancel. I think there can be little doubt that the latter of these is one of the twelve consecration crosses, which, in accordance with mediaeval usage, were placed upon the internal as well as the external walls of new churches. The instructions were to place them in circles, ten palms, i.e. 7ft. 5in., above the floor; but this rule appears to have been more honoured in the breach than the observance.

A plain font "of competent size" stands in the south aisle near to the doorway. It is cut out of three large blocks of limestone. The bowl is lined with lead.

In an improvised vestry, near by the font, there is a discarded Jacobean Holy-table, 6oin. by 29m., uninscribed and undated.

The suggestion that the western wall of the church was built as a temporary expedient, is strengthened by the absence of a tower arch, and while this fact, by itself, is not conclusive, the "straight joint" in the reveals of the small pointed doorway which was cut through the wall to form the only means of access to the tower, clearly proves that the steeple was built up against this temporary wall. (An external doorway has been rudely cut through the western wall of the tower in modern times, see plan.)

The Royal Arms, modelled in plaster, and gilded, are placed on an oak board above the tower doorway, in accordance with a custom which commenced at the Reformation, and became compulsory at the Restoration. These arms do not antedate the union with Ireland in 1801, and may appertain to George III. or William IV.

Higher up in the western wall, almost close to the roof, is a small opening 6½in. wide, 2ft. 4½in. high. To ascertain the purpose for this, we must ascend a circular staircase which starts in the north-east angle of the tower and extends to the battlements. At the top of the first flight of steps there is a door which leads into a tower chamber 10½ft. square. There can be little doubt that this chamber was made for the use of a sacristan, whose duty it was to ring the bells at the celebration of the parish mass, to attend to the lights of the altars, and to fasten the doors of the church. This suggestion is supported by the fact that the steps are worn hollow by daily use; the church doors, as we have already noticed, were secured from within; the little window in the west wall of the nave, before mentioned, gives a clear view of both altars; and further we may learn from the Inventory that a sanctus bell once hung in the steeple.

If these surmises are correct, then it follows that the low-silled window in the south wall of the chancel was not provided for ceremonial purposes, but simply to give light at a particular point, probably the reader's desk. Stretton says that it was made to light the manor pew, but the squire's pew would not find a place in the chancel until after the Reformation, at any rate, in which case the pew would be fixed against an existing window, which does not explain the original purpose.

The "Instructions" as to bell-ringing as part of the service of the mass, were issued a hundred years before this church was built, and it would be a reflection on the skill of the builders to suggest that, given a free hand, as in this case, unhampered by existing conditions, they could only meet the requirement by a sort of afterthought arrangement, such as is found in more ancient buildings which were already in use when the Instructions were issued.

Before leaving the chamber, to complete the ascent, the wooden frame and iron works of a derelict clock should be noticed. Inscribed on the oak framing, which is 6½ft. high by 3½ft. wide, are the initials I.N., and date, 1735.

During the 18th century, many Nottinghamshire villages could boast an expert clock-maker, and it is no unusual thing to find the remnants of a home-made clock in the village churches of this district. There was an identical piece of work at Cropwell Bishop; another at Shelford, marked R.R., 1680; and still another at East Leake. A celebrated clock-maker, named Rowe of Epperstone, made a clock for the Church of St. Nicholas at Nottingham, in 1699,1 and one for St. Mary's in 1707, while still another of his clocks was formerly in the tower at Linby. Not many of these old clocks are now in use. I suggest that in the hands of an expert the story of these rural clock-makers would prove to be an interesting one, and therefore this digression is pardonable.

The belfry contains a frame for three bells, and it is evident that three bells have been in use, but one was cracked and removed some time ago and only two bells are now hung. The inscriptions are:—

1. IHS be ovre sped. Lombardic capitals, and an ornament 4¼in. square, which is sometimes found on bells cast by Henry Oldfield.

2. William Harrison & William Wordsworth, 1617. Roman capitals, and the better known mark and initials of Henry Oldfield.

Returning to the nave, and looking towards the east, the narrow chancel arch attracts notice by reason of its unusual proportions—9ft. 4m. wide by 17ft. 6in. to springing line. When we come to ascertain who it was that built this church the peculiarity of the chancel arch will be a point to consider. In the meantime, we may be quite sure that this treatment was intentional and not the result of caprice, for if the tower chamber was used for the purpose suggested, a lofty arch would be necessary to give an uninterrupted view of the high altar.

The fragment of screenwork set in between the reveals, now only serves to emphasize the narrowness, but when rood-screen and loft stretched across the full width of the nave, the abnormal height of the jambs was cloaked thereby, for then only the outline of the arch would be visible above the loft, with the rood in silhouette.

The screen was destroyed in 1810. What a loss the destruction of this screen entailed upon the church can best be realized by a visit to Strelley, where a similar rood-screen remains almost intact. If we may judge by the remnant at Barton, and the fragments of screenwork now made up into a reading desk, at Wilford, the three churches under notice were each fitted with a rood-screen, after the 15th century Midland type, and made by local craftsmen. There was close connection between Wollaton and Strelley since the marriage of Saunchia Willoughby and John Strelley, (born c. 1449), and the great similarity of the windows and the family tombs, &c., makes it seem not at all unlikely that the screens were similar also.

The upper doorway, which gave access to the loft, at Barton, may still be discerned, now blocked up with masonry, in the eastern respond of the pier arcade.

The wooden pulpit is contemporary with the discarded Jacobean Holy-table now in the vestry, but the carving on the larger panels is modern.

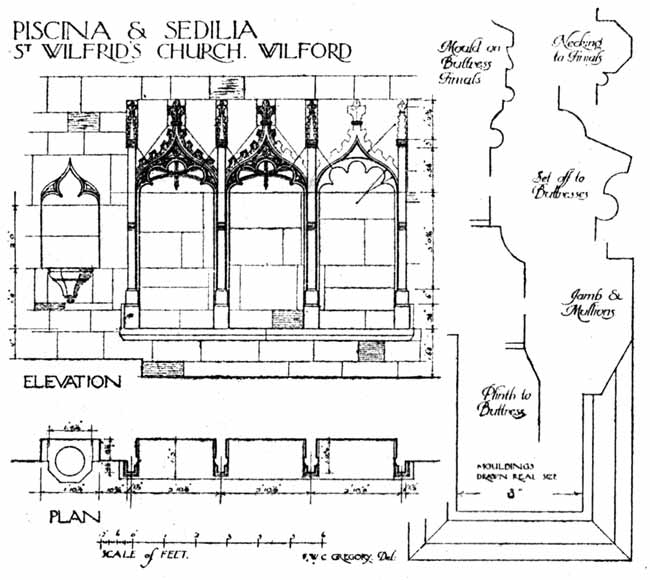

It is clear to my mind that the outer walls of the chancel were built while the old nave was standing. The wall between chancel and nave was then built, in such a way, as to allow the chancel to be used for service while the nave was being taken down and rebuilt, and this may be one reason for the narrowness of the chancel arch. This arch consists of two orders of chamfers, and it should be noticed that the inner order springs from moulded semi-octagon pendant corbels of characteristic design. A similar treatment is adopted for the terminals to all hood-mouldings throughout this church, and even for the springers of the diminutive quasi-vaulting ribs in the head of the sedilia (see line drawing). This appears to have been a favourite detail, and a distinguishing feature in the work of this particular band of craftsmen. Carving and sculpture is not anywhere employed, except very sparingly on the sedilia and image bracket.

The sedilia in the south wall of the chancel comprises three ungraded seats, with canopied ogival heads, cinquefoil cusped, and with carved crockets and finials. The piscina niche has a plain cusped ogival head with two small recesses sunk in the head-stone to contain the crewets. It was a pre-Reformation custom, when the cup was denied to the laity, for the priest to "make the chalice" in the sight of the people. For this purpose two small vessels of silver or pewter, about 6in. high, were used. The one containing water was marked A (qua); the other containing wine was marked V (inum). The Inventory taken in the 6th year of Edward VI. would undoubtedly contain reference to the crewets, but unfortunately it is not in existence. All that we can now learn is that "one challis of sylver with a patente gylte, for the admynstracone of the holye comunyon" were the only altar vessels allowed to remain. There is a piscina niche of like design in the south aisle, where an altar once stood. Opposite to it, and in correspondence with it, is an almerie. These piscinal niches with recesses for the crewets were once fairly common, but I believe Barton is now unique, in the county, in this respect.

(1) "16—Rich' Roe fecit de Eperstone—99." Old clocks have also been noticed at Hickling, Owthorpe, and Whatton.