By referring to one of my earlier sketches, I find that originally these windows were of three-light tracery of simple design, similar to the windows in the north aisle at Gedling, hereinafter illustrated.

The walling of the south aisle at Plumtree is composed of blue lias rubble, mixed with large boulders gathered from the fields, with dressings of local "water-stone" or skerry. This appears to have been the earlier traditional manner of building in the district; for it corresponds with the older work in the lower part of the western tower of the same church, which is presumably early Norman, and embodies fragments of Saxon work; also with the older parts of the neighbouring churchcs of Stanton-on-the-Wolds, East Leake, Wysall, &c.

Two-light windows with intersecting tracery are also found at Linby, West Leake, Willoughby-on-the-Wolds, Edwinstowe, Carburton, and in the steeples at Burton Joyce and Bingham. Good examples of three-light windows of the same class are to be found at Blyth (Vol. V.), Bunny, Sutton St. Ann's, and Skegby.

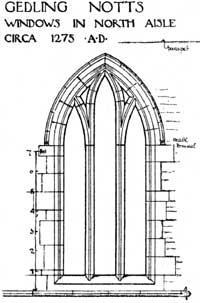

The illustration from Gedling, in grouping a number of lancets under one containing arch, shews another development. This window was constructed during the last quarter of the 13th century. There is a smaller example at East Leake, where the triple arches were all cut out of one plate of stone. This latter window is interesting, because the head of the original single lancet, which it displaced, is still in situ; thus showing that the grouped arrangement originated in a desire for more light within the chancel.

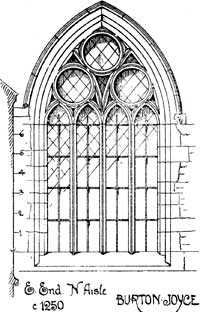

However economical intersecting tracery may have been, the architectural effect produced is thin and far from pleasing. It evidently failed to satisfy the mediaeval builder, for many attempts were made to improve upon it by the introduction of circles and other geometrical forms, (see Burton Joyce 1240-1315).

By the second half of the 13th century a new phase was brought about by the general adoption of "featherings" or "cusps." Even in Norman times, builders had experimented with a trefoiled arch, i.e., an arch wherein the whole mass followed the line of a trefoil, and this seems to have been the inception of what afterwards became an elaborate system of foliation; it was the introduction of cusps, which brought about the great change in window design and opened a way for unlimited development.

Seeing that cusping played such an important part in the succeeding styles, it may be well to define the terms necessary to the understanding of it.

A cusp is the projecting point forming the foliations or featherings; a foil is the space between the cusps.

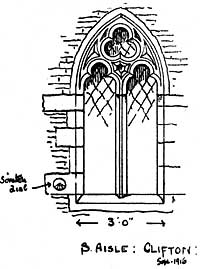

When an enclosed space is divided by cusps so as to resemble three leaves—see illustration of Clifton, and Sutton-in-Ashfield (Plate II.)—it is said to be "trefoil"; if four leaves, "quatrefoil"; five leaves, "cinquefoil," and so on.

The "fillet" is the narrow front face of the tracery; the "soffit" is the flat face at right-angles to it next to the glass-line; the "chamfer-plane" lies between the fillet and the soffit, and may be either a chamfer, a moulding, or a hollow-chamfer, according to the style and period of construction.

At first, what is known as soffit cusping was adopted; that is to say, the cusps sprang from the soffit only, and were consequently inconspicuous. Soffit cusping is therefore an indication of early date: see illustrations from Selston and Sutton-in-Ashfield (Plate II.), and the east window at Stapleford (c. 1300). (Plate I.). This latter would appear to have been a favourite design for an east window; for we find it used with scarcely any variation, in churches as wide apart as Stapleford, Averham and Hucknall. In the latter the jambs only are original work; the tracery has been restored on original lines. In each case, a five-light intersecting tracery window is embellished with shallow soffit cusping in the uppermost central light only. At Lowdham, the windows at the east end of the chancel and the south aisle, each of four-lights with intersecting tracery, have cusping in all the lights. These windows were wrought about the middle of the 14th century.

PLATE I. Stapleford church.

As time went on, cusps grew in prominence until they eventually embraced the whole of the chamfer-plane, and became the most conspicuous part of the design.

Before we go on to consider the 14th century or Decorated style of window, with its sub-divisions of Geometrical and Curvilinear tracery, let us pause for a moment to notice a window of peculiar design in the chancel of Elston church.

In general outline, it conforms with the intersecting tracery of the 13th century, while the mouldings and the shafted jambs and mullions, with their carved capitals and moulded bases, are suggestive of late 14th century work; and yet there are no cusps !

I have not met with a similar design anywhere in the county, and it is just one of those things that makes the study of local architecture so very interesting. The question naturally arises, why was cusping, by this time almost universal, not adopted here? One would need to be intimate with all the circumstances and conditions of village life in the epoch of this particular church, before venturing to frame an answer. It may be, that the craftsman lived in obscurity, and knew not all that was being accomplished in the field of art; it may be that he knew, but did not feel competent to perform; or it may be, that such local material as was available was deemed unsuitable for the delicacies of foliated work: albeit the capitals are nicely carved and all the arrises are still sharp. It is but one of the interesting examples of local genius, of which there are more to follow.