Thurgarton Priory tower.

Thurgarton Priory tower.Only three of the aisle arches remain on either side of the nave. The piers which support these arches are very massive, alternately square and diagonal in plan, different in detail and enriched with clusters of subordinate pillars, which give also some lightness to the general effect. Notice the south-west capitals, which are so constructed as to imply the former existence of a south nave, south-west archway, and south-west tower.

If, last of all, we go up the staircase in the tower, we shall come to a series of arches over the present roof which give the line of the old clerestory windows with arches below, indicating the old triforium. The heads of these clerestory windows are about 5ft. below the line of the 13th century gutter marked on the tower. The old aisle roof at the highest point was 5ft. above the present nave roof gutter, or 3ft. 6in. above the springing of the arches of the old triforium. These figures demonstrate the fact that the old line on the east side of the tower is the line of the 13th century aisle roof. There are three bells:—

The big one, which is the clock bell, dated 1618, bears the inscription—"Thomas Holland and Randull Pears, Wardens."

The middle one, dated 1607, bears Henry Oldfleld's bell-mark and the legend, "I, sweetly toling, men do call to taste on meats, that feeds the soule." The small bell is dated 1699, and also bears Henry Old-field's bell-mark aud the inscription—" R, Arnold, Warden," with the legend, "Jesus, bee our speede." Coming down to recent times, we ought perhaps to remark that the nave and aisle of this church were restored in 1854 by Mr. Richard Milward at a cost of more than £3,000. The Chancel was added at the same time. The stained glass East Windows were given by him in 1875. A sum of £500 for the erection of the Chancel was also contributed by the Master, Fellows, and Scholars of Trinity College, Cambridge, who have been rectors and landowners here since the dissolution of the priory. When Mr. Milward came to live here the church was in a wretched state and its aisle arcades were incorporated in the outer walls.

As early as 1790 John Throsby speaks of the church as then consisting of one dark aisle, the rest being totally destroyed. He also says: " Mr. Rastall feels much for the demolition of some part of this monastery, which was a kitchen vast and magnificent almost beyond parallel."

The present mansion was built in 1777 by Mr. John Gilbert Cooper, of Southwell, who swept away all the older work that was left in his time, with the exception of the undercroft or crypt, which still exists in good preservation below the present house. This crypt measures 701/2ft. by 251/2ft. It is bisected lengthwise by six pillars, is plainly vaulted, and has exterior walls, with narrow windows to the west. Portions of the undercroft are hidden by modern walling which now subdivides it, and some of the original vaulting has been replaced by a poor brick vault, probably in 1777. Bishop Trollope used to speak of it as the Domus Conversorum or workshop of the priory, of which a fine specimen remains at Fountains Abbey; but others, including the present vicar, regard this undercroft as too ill-lighted for this purpose, and are of opinion that it is more likely to have been the cellar of the 13th century priory, as it most certainly is of the 20th century episcopal residence.

The house which preceded the present one appears from Buck's print to be of Elizabethan date, with the exception of the fine monastic kitchen referred to above.

Monastic buildings of this kind were grouped round an open square and surrounded by a cloister. This was usually fitted into the warm and sheltered angle formed by the south side of the nave and the south transept. The usual arrangement of the monastic buildings round and adjoining the cloister varied in details; but the general principles of disposition were fixed early. They are embodied in a manuscript plan, dating as far back as the 9th century, and found at St. Gall, in Switzerland, and never seem to have been widely departed from. The monks' dormitory in that plan occupies the whole east side of the great cloister, there being no chapter-house. It is usually met with as nearly in this position as the transept and chapter-house will permit. The refectory, according to the St. Gall plans, is on the south side of the cloister, and has a connected kitchen. The west side of the cloister was occupied by a great cellar. The infirmary was placed to the east of the chancel of the church, and the granaries, mills, bakehouses, schools were placed more remotely still from the west.

If the St. Gall plans were adopted at Thurgarton, and, as I have said, they were rarely departed from, this western undercroft most have been the cellar of the 13th century priory, rather than its Domus Conversorum or workshop.

[When this paper was read at Thurgarton Priory, the following was omitted.]

Very little is known of the individual lives of those who generation after generation spent their days at Thurgarton Priory. We do possess, however, a mystical treatise called The Scale (or Ladder) of Perfection, written by one Walter Hylton, a canon of Thurgarton. The book has been reprinted from the edition of 1659, with an introduction by the Rev. J. B. Dalgairns. Hylton lived near the end of the 14th century, and though little is known about the author's life, his book was widely read, and was "chosen to be the guide of good "Christians in the courts of kings and in the world." The mother of Henry VII., Margaret Beaufort, is said to have valued it very highly.

There are two lives, he teaches, the active and the contemplative; but in the latter there are many stages. The highest kind of contemplation a man cannot enjoy always, "but only by times when he is visited;" "and as I gather "from the writings of holy men, the time of it is very short." Visions and revelations of whatever kind" are not true con-"templation, but merely secondary. The devil may counterfeit them;" and the only safeguard against these impostures is to consider whether the visions have helped or hindered us in devotion to God, humility, and other virtues." In the "third stage of contemplation," he says finely, "reason is "turned into light and will into love." The true light is love of God, the false light love of the world. But we must pass through darkness to go from one to the other. "The darker "the night is, the nearer the day." It is gratifying to find that our Canon of Thurgarton shakes off here, easily and unconsciously the older nihilism of the mystics; the "negative road" which leads to darkness and not to light. Hence our countryman's mysticism is sounder and saner even than Eckhart's or Tauler's.

Before leaving him it may be worth while to quote two or three isolated maxims of his as examples of his wise and pure teaching. "There are two ways of knowing God—one "chiefly by the imagination, the other by the understanding. "The understanding is the mistress, and the imagination is "the maid." . . . . " What is heaven to a reasonable "soul ? Nought else but Jesus God." . . . . "Ask of "God nothing but this gift of love which is the Holy Ghost. "For there is no gift of God, that is both the giver and the " gift, but this gift of love."

The following extracts from the statutes of the Black Canons will give us some idea of their rule and way of life:—

"Quod omnes Canonici omnibus horis canonicis interesse tenentur. Post completorium dictum a conventu, accepta aquae benedicta ab eo qui dare solet, immediate ad dormitorium simul regulariter transeant, ubi silentium teneant. In dormi-torio in cellulis distinctis singuli in singulis et separatis lectis cubent et jaceant; et quadibet cellula, dum in ea aliquis canonicorum fuerit, toto die quo inibi invaserit, tarn de die quam de nocte, ab anterior! parte sit aperta, ut introspicere volentes videre possint quod intus agatur. In refectorio consuetam lectionem habeant, cui attentas aures accommodent ac silentium teneant. Matutinas et alias horas canonicas in choro simul omnes canonici distincte et sonora voce alternatim omni devocione teneantur (habere), missam quoque cantent; uno celebrante ceteri omnes in choro intersint orationibus aut contemplacionibus intendentur. Omnes de eodem monasterio habitu unius colons et ejusdem forme utantur, et tonsuram gerant uniforme . . . . . utantur vestibus honestis albi, nigri, quasi nigri coloris." (Stat. Ord. 1519; Cotton MS., vesp. F. ix. f. 22, 31.)

In conclusion, an old distich tells us that the Franciscan loved the town, the Jesuit the city, the Cistercian the valley, and the Benedictine the mountain. The Benedictine was the citizen, the chronicler, the most learned of monks; the Cistercian was the educator of the poor, the friend of the labourer ; the Clugniac combined the fine arts, reading, and study with labour and agriculture; the Carthusian was the ascetic of religious life; the Dominican was the preacher eager for the development of thought, truth, and philosophy; the Franciscan Minor was the preacher of equality; the Austin Friars were proverbial for their logic, and the Austin Canons for their love of preaching. It does seem to have been a fatal error at the Reformation not to have devoted their stately houses, their beautiful churches, and their splendid foundations to charitable uses, study, and religion. But even now we may still gather up the fragments of the goodness and greatness they once held fast; we may still retain many of the great lessons they taught, and as we treasure them in our hearts, may go forward in our day and generation with firmer and surer feet.

The following remarks written by Mr. Christian on visiting the church about the year 1852, shortly before its restoration, will be read with interest. Of course the "east front" spoken of in his remarks is merely the wall which closed up the end of the fragment of the original nave, which fragment, together with the tower, then constituted the whole church. In this wall were the two 14th century windows now at the east end of the chancel which was added to the nave in 1854.

THURGARTON.

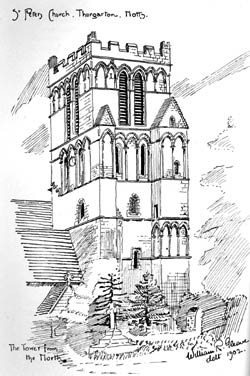

Remains of the Abbey-Church very singular and not comprehensible on a hasty glance. As it appears now it has an east front of great beauty, though partially ruined; and at the west end, an archway of exceeding richness and late E. E. has been filled with glass, to form an enclosure giving light into the church. At the north-west angle is the tower, of great height and beauty of detail, but not by any means in a perfect state. The entrance is through this tower by a small but beautiful doorway, in which there still remains the ancient door and hinges. The mouldings in the arch of this doorway and in the arch of the west wall are of the richest character in E. E., arranged in well-defined masses, and relieved by plentiful series of the 4-leaf ornament. The south wall, being next the Hall which now occupies the site of the Abbey part, is not visible, and the north wall, from its imperfect state, was evidently not originally intended for the exterior. The east wall is of very beautiful Early Decorated character, and has a peculiarly rich and delicately moulded double window, each part of two lights with a quatrefoil head. The window has a central and two side pillars, and each of the mullions and the corresponding members of the jambs are finished with attached shafts and exquisitely moulded caps and bases. Internally, the central mullion has not a perfect pillar, but a beautiful canopied niche with a richly foliated terminal and corbel. This niche appears to have been elaborately finished in colours. The interior, except in this particular, presents but few features of interest, but many barbarisms have been perpetrated within its walls. Several oak benches remain of very early character. The east wall would afford much food for speculation. I do not think it was originally finished with a gable, and the stones, having been much hacked and roughly finished under the tiles, would appear to favour this view; but how it was finished, my hasty observations would not enable me to determine. At any rate, the form now given to the wall has the advantage of a very pleasing outline, and combined with the rich details, the result is most satisfactory. Close to the tower on the north wall is a porch with a rich E. E. archway. This, as it evidently does not belong to the wall, must have been moved to the site it now occupies, and probably at no distant date. The situation of the church is very secluded, exceedingly beautiful, and whether to the artist or the architect, the spot presents attractions of no ordinary interest.