CHAPTER I

THE FIRST BENTINCK A HERO

What a delightful story is that of the Portland peerage, in which fidelity, heroism, chivalry and romance are blended and interwoven in the annals of the noble families of England. Who that has been to Welbeck Abbey, that magnificent palace in the heart of Sherwood Forest, with its legends of Robin Hood and his merrie men, with its stately oaks and undulating woodlands, stretching away to fertile pastures, dotted over with prosperous farmsteads, as far as the eye can reach, does not feel interested in the fortunes of the noble owner; and who that has seen the Duke and Duchess on some festive occasion at Welbeck, moving to and fro among their thousand guests, a perfectly happy couple, in which the course of true love runs smooth, and whose supreme delight appears to be to spread happiness around them, is so churlish as not to wish them long life, as types of the English nobility it is a delight to honour?

There is no affectation about this illustrious pair, the Duke never poses in relation to affairs of State, and the Duchess has a natural grace all her own, to which art can add no touch of dignity.

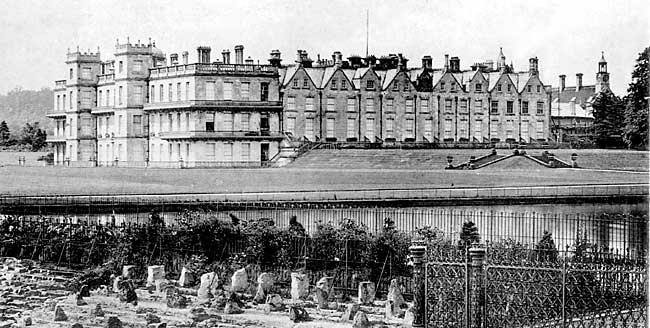

Welbeck Abbey, c.1890.

Welbeck is now the home of peace and joy; but there have been times when its history has been shrouded in tragic mystery, and even to-day there is the Druce claim to give piquancy to its story.

The family springs from the alliance of the Bentincks and the Cavendishes. Theirs is a telling motto: Dominus providebit (The Lord will provide) was on the crest of the Bentincks, and it befitted a family not too richly endowed with this world's goods according to the position of the Dutch nobility 250 years ago; but being of sterling qualities devoted to the cause they espoused, their descendants have met with their reward. Craignez honte (Fear disgrace) was another motto of the family, and the fear of dishonour has been a characteristic trait from the time when the first Bentinck set foot in England, till today.

Before unfolding the drama of tragedy, love, and comedy of these later years let us go back to the tale of heroism surrounding the character of the first Bentinck to make a name for himself in this country. Englishmen are apt to forget the debt of gratitude owing to men of the past; had it not been for Hans William Bentinck this favoured land might still have been under the Stuart tyranny, and the scions of the House of Brunswick might never have occupied the Throne of Great Britain.

James the Second had made an indifferent display of qualities as a ruler, and the nation was tired of a superstitious monarch who was fostering a condition of affairs which was turning England into a hot-bed of religious and political plots and counter-plots. James's daughter, Mary, had married William, Prince of Orange, who was invited to come and take his father-in-law's place as King of England. That invitation was extended in no uncertain way, and James having withdrawn to the continent left the vacancy for his son-in-law and daughter to fill.

Hans William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland (1649-1709).

When William of Orange came over at the request of many of the nobility and influential commoners in this country there was in his train, Hans William Bentinck, who had previously been to England on a political mission for the Prince.

Bentinck was of noble Batavian descent and served William as a page of honour. His family had its local habitation at Overyssel in the Netherlands and still is know there. At Welbeck a curious old chest, made of metal and carved, is one of his relics, for in it he brought over from Holland all his family plate and jewels.

The Prince was delicate of constitution and his ailments made him passionate and fretful, though to the multitude he preserved a phlegmatic exterior.

To Bentinck he confided his feelings of joy and grief, and the faithful courtier tended him with a devotion which deserves the conspicuous place given to it in English history.

The Prince was in the prime of manhood when he was seized with a severe attack of small-pox. It was a time of anxiety, not only on account of the possible fatal termination of the disease, but in an age of plots, of the advantage that might be taken to bring about his end by means of poison or other foul play.

It was Bentinck alone that fed the Prince and administered his medicine; it was Bentinck who helped him out of bed and laid him down again.

"Whether Bentinck slept or not while I was ill," said William to an English courtier, "I know not. But this I know, that through sixteen days and nights, I never once called for anything but that Bentinck was instantly at my side." Such fidelity was remarkable; he risked his life for the Prince, who was not convalescent before Bentinck himself was attacked and had to totter home to bed. His illness was severe, but happily he recovered and once more took his place by William's side.

"When an heir is born to Bentinck, he will live I hope," said the Prince, "to be as good a fellow as you are; and if I should have a son, our children will love each other, I hope, as we have done."

It was about the time of the Prince's perilous voyage to England to fight, if need be, for the Throne, that he poured out his feelings to his friend. "My sufferings, my disquiet, are dreadful," he said, "I hardly see my way. Never in my life did I so much feel the need of God's guidance."

At this time Bentinck's wife was seriously ill, and both Prince and subject were anxious about her. "God support you," wrote William, "and enable you to bear your part in a work on which, as far as human beings can see, the welfare of His Church depends."

In November, 1688, the Prince landed in England, and with him was Bentinck, accompanied by a band of soldiery, called after his name, as part of the Dutch army. The Prince and his wife were eventually declared King and Queen, and Bentinck experienced substantial proof of the royal favour by being given the office of Groom of the Stole, and First Gentleman of the Bedchamber, with a salary of 5000l. a year. Not long after, in 1689, he was created Earl of Portland, and his other titles in the peerage were Baron Cirencester and Viscount Woodstock; he was also a Knight of the Garter and Privy Councillor. In 1689 he accompanied the King to Ireland and commanded a regiment of Horse Guards, taking part as a Lieutenant-General, in the battle of the Boyne, where his Dutch cavalry did effective service.

He was again at the battle of Namur when William's forces were engaged in fighting the French for the liberties of Europe.

That was in 1695, and in the same year the King once more gave evidence of the affection he bore for his favourite. "He had set his heart," said Macaulay, "on placing the House of Bentinck on a level in wealth and dignity with the Houses of Howard and Seymour, of Russell and Cavendish. Some of the fairest hereditary domains of the Crown had been granted to Portland, not without murmuring on the part both of Whigs and Tories."

It was perfectly natural that William should wish to requite his henchman with rich estates, and in doing so he was acting as other monarchs had done before him, and not upon such good grounds as the services rendered to the State by Bentinck.

Jealousy was, however, aroused among the English nobility at the favouritism shown the Dutch newcomer, and it found strong expression when the King ordered the Lords of the Treasury to issue a warrant endowing Portland with an estate in Denbighshire worth 100,000l, the annual rent reserved to the Crown being only 6s. 8d. There were also royalties connected with this estate which Welshmen were opposed to alienating from the Crown and placing in the hands of a private subject. There was opposition to the grant in the House of Commons and an address was voted, asking the King to revoke it.

Portland behaved with great magnanimity in the matter, his one chief desire appeared to be to avoid a quarrel between his royal friend and Parliament. Not many men would have had such self-abnegation as to renounce an estate estimated to be worth 6,000l. per annum, besides the product of royalties, when they had a King and a victorious army to support them in its possession. The Earl had saved the King's life, he had rendered invaluable services as a diplomatist and General in raising forces to fight for the cause of Protestantism; but for him the probabilities were that James would have retained possession of the Throne and that red ruin would have spread itself over the land. Surely he had won as great a reward as those of the nobility whose only recommendation was that they were the natural sons of royalty.

To have refused this immense estate simply because he was the victim for the time being of racial jealousy is a rare and conspicuous instance in English history of self-sacrifice to honourable motives. His uprightness of character was again tried by the East India Company, who offered him a 50,000l bribe to exert his interest on behalf of that Corporation; but he was not to be tempted by the offer. It will be seen later how the great families, such as Cavendish, became allied with that of Bentinck when the pride of nationality had been reconciled.

Once more in February, 1696, was Portland the means of saving the King's life, through the information he had received of a plot for his assassination by the Papists. The details of the scheme were eventually laid bare and the conspirators brought to justice.

Few men have had a life so full of activity and importance to the State as this Hans William Bentinck. While the Ambassadors were tediously endeavouring at Eyswick to bring about peace between England and France and not making much progress, William took the unceremonious course of sending Portland to have an interview with Marshal Boufflers as representing Lewis. Both were soldiers and men of honour. The meeting took place at Hal, near Brussels, where their attendants were bidden to leave them alone in an orchard. "Here they walked up and down during two hours," says Macaulay, "and in that time did much more business than the plenipotentiaries at Eyswick were able to despatch in as many mouths."

"It is odd," said Harley, "that while the Ambassadors are making war the Generals should be making peace." In the end the terms these two men negotiated were elaborated in the Treaty of Ryswick, which was the great instrument consolidating William on the Throne, wresting England from the Stuart ascendancy and completing the work of the Revolution.

Such is an outline of the vicissitudes which this extraordinary man passed through in the course of his exciting career. He died in 1709 and was succeeded by his son.

Henry, the second Earl, was Governor of Jamaica, and created Marquis of Titchfield and Duke of Portland in 1716. His death took place in 1726, and he too was succeeded by his son.William, second Duke, was a Knight of the Garter, as most of the other holders of the title have been, and he died in 1762. It was through his marriage with the grand-daughter of the Duke of Newcastle that the Bentincks became possessed of Welbeck.

He was succeeded by his son, William Henry Cavendish-Bentinck, third Duke, K.G., who had been M.P. for Weobley. This Duke became Prime Minister of England in 1783, when a Coalition Government was in office. Again in 1807 he was Premier, and was at the head of the Ministry up to shortly before his death in 1809. Other positions held by him were Viceroy of Ireland, Secretary of State for the Home Department, 1794; Lord President of the Council, 1801; Chancellor of Oxford University; High Steward of Bristol and Lord Lieutenant of Notts.; he assumed the additional name of Cavendish by royal licence in 1801. He received his early education at Eton, but in after life declared that he got nothing out of Eton except a sound flogging. It was not claimed for the Duke that he was a man of brilliant attainments, but he was the soul of honour, and for this reputation and for his conciliatory disposition, was chosen to head the Government, which relied for its precarious existence on the reconciliation of the contending parties among the Whigs and Tories. He married the only daughter of the Duke of Devonshire and the male direct line continued in the succession of his eldest son.

The fourth Duke was William Henry Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, who married Henrietta, eldest daughter of Major-General John Scott, a descendant of Balliol and Bruce, the heroes of Scottish history. There were four sons and six daughters of the marriage, the succession being continued by the second son. The fourth was known as the "Farmer Duke," and with his love of country presuits he lived to the ripe age of eighty-five, dying in 1854.

The most eccentric character in this ducal line was the fifth holder of the title, William John Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, born in 1800. He was M.P. for Lynn 1824-1826, and died in December, 1879. Of his extraordinary predilections more will be related in succeeding chapters.

The sixth and present Duke is William John Arthur Charles James Cavendish-Bentinck, who was born on December 28th, 1857, and succeeded to the title in 1879. His elevation to the Dukedom is an example of the fortune of birth; the old and eccentric Duke died unmarried, or so it was assumed, and therefore his honours in the peerage passed to his second cousin.

To trace the lineage of the present Duke we must go back to the third Duke, who had a third son (Lord William Charles Augustus). This third son, who was uncle of the eccentric Duke, had issue, Lieut.-General Arthur Charles Cavendish-Bentinck, the father of the present Duke, his mother being Elizabeth Sophia, daughter of Sir St. Vincent Hawkins Whitshed, Bart. The name of Scott was not part of his cognomen; he sprang from another branch in which there was no trace of the Scott element, and the name having been borne by two Dukes for a lady's fortune, there was no further obligation to continue it in connection with the Cavendish-Bentincks.

The marriage of his Grace took place in 1889 to Winifred, only daughter of Thomas Dallas-Yorke, Esq., of Walmsgate, Louth, and their children are: William Arthur Henry, Marquis of Titchfield, Born March 16th, 1893, Lady Victoria Alexandrina Violet, born 1890, and Lord Francis Norwen Dallas, born 1900.

The Duke was formerly a Lieutenant in the Coldstream Guards, then after succeeding to the title, he became Lieut-Colonel of the Honourable Artillery Company of London; he is also Hon. Colonel of the 1st Lanarkshire Volunteer Artillery, and 4th Battalion Sherwood Foresters Derbyshire Regiment. He is Lord Lieutenant of Notts, and Caithness, and was Master of the Horse from 1886-1892 and 1895-1905. He is a family trustee of the British Museum, and is the patron of thirteen livings. The Portland estates comprise 180,000 acres, and his income is estimated at 150,000l. a year from them alone.

Besides Welbeck Abbey, he has country seats at Fullarton House, Troon, Ayrshire; Langwell, Berriedale, Caithness; Bothal Castle, Northumberland, and a London residence at 3, Grovesnor Square.

There are still descendants of the Hon. William Bentinck, eldest son, by the second marriage of the first Earl of Portland. The Hon. William was born in 1704 and created a Count of the Holy Roman Empire in 1732.

The vast fortune of the House of Portland has been built up in a remarkably short space of time, a little over 200 years, and no other great family has received so many honours and acquired such wealth in the same period. In the last century one of the Dukes held fourteen different public offices at the same time, while a younger son was Clerk of the Pipe, and a brother-in-law and nephew had 7,000l. per annum in official salaries; a daughter too was the recipient of a State pension for pin-money.

One of the characteristic traits of the Bentincks has been that in founding the fortunes of the family in the past their scions were successful in capturing great heiresses. These brief genealogical details will help to explain future developments in the history of this noble family.