THE CHURCH WARSOP DOVECOTE.

CHURCH WARSOP COTE.

CHURCH WARSOP COTE.INSTEAD of having the dovecotes in alphabetical order, I shall give a description of them in the order I saw them, and the first one I visited was at Church Warsop, which is about five miles from Mansfield, and it was on February the 3rd, 1927. It stands just outside the farm buildings to the North-west of the Church, and is a very substantial building. The material used is limestone, quarried in the neighbourhood, a stone that wears well and looks well. The roof now is tiled, but I should say when it was first built it had a thatched one, and the date would be in the Tudor days, probably when the Church was built. It is now the property of Sir Hugo FitzHerbert, Bart. It is twenty-four feet high to the square of the walls, which are two feet nine inches thick, and the door into it is five feet three inches high and two feet six inches wide. In size the cote is nearly a square, being twenty-four feet from west to east, and twenty-two feet from north to south. The stones in the walls vary a lot in size; some are quite small, others of large dimensions, they are roughly dressed on the outside and on the inside. In these walls are six hundred and fifty nesting places, each one having a separate slab of stone for the pigeon to alight on. They stand out from the wall about six inches, and are oval in shape. The entrance to each nesting place is eight inches high and six inches wide, and the passage is fourteen inches in length. On the left, near the end, is a circular space for the nest. These were made as the walls were built up, and must have taken a lot of time as they are smoothly dressed. On the outside of the walls are two string courses. These are to prevent rats and other vermin from getting up to the roof. One is just above the door, five feet up, and the other about twelve feet above the ground. In cotes of square shape, with well built walls, they are not so wide as in tower or round shaped ones. These latter have the tops smaller than at the ground level, so slant somewhat, and though very gradual they would be much easier for rats to get up than on a plumb wall. These vermin, however, are wonderful climbers and very persevering and suceed in getting up places that one would think it quite impossible for anything without wings to do so. Old as this building is, the walls are in very good condition, and look like lasting for many years yet. The cost of this cote must have been considerable, though money in those days went much further than in these times, and the mortar was very different and set as hard as cement does now. Very little sand was used, and more time given to the mixing than in these times of rush and contract. Of course, all cote walls that had nesting places in them had to be thick ones, but where the walls were only double brick the boxes were placed in wooden frames, and each compartment was of wood, or wattle, and in the latter the nests were made of clay or lime, and hair. This fine cote is now used for storing farm implements, a dull silent place, and very different from the days when it was inhabited by hundreds of pigeons. During spring and summer, and deep into the autumn, they would be coming and going, bringing food for their nestlings, and returning for more, and scores of others would be sunning themselves on its roof, and the place would resound with their cooings. These notes are soft and low when the birds are making love to each other, but short and gruff when angry. When they fight they do not use their beaks as much as some birds do, but side up to each other and slap with their wings. During the winter they go further afield for food, and feed on the grain that has been left from the harvest, and on the small seeds growing amongst the stubble, thus they do much good. Then when “evening shadows” are falling they rush homewards on swift pinions, for evening is the time they are fed, not in the morning, because their owners well know they will certainly return then, and if one fed and another did not many pigeons would be lost, especially when cotes are not very far apart, so it was a wise policy not to spare the corn in the evening. After feeding they pass into the cote, some into their nesting holes, others roost on the tops of the walls and on the beams. Here they enjoy a peaceful rest which they have well earned, for it is known that with the pies they provide and the money for those sold, a dovecote is a good investment, to say nothing the wonderful fertilizing power of the cleanings of the cotes, which should be done at least twice a year.

THE DOVECOTE AT EPPERSTONE.

MAJOR T. HUSKINSON’S.

EPPERSTONE COTE.

EPPERSTONE COTE.ON the 9th of February, I motored over to Epperstone to see Mr. Huskinson’s cote. It was a typical winter’s day, with a keen north-easterly wind which would have shaved the beard off an oyster. We passed through Oxton, a pretty village, and then along the road below Epperstone and Oxton Park Woods, where in days long past I have seen many a fox found. They are large and beautiful pieces of woodland, where I have shot. This cote stands in a grass paddock at the lower end of the village. It is a small one, but pretty in shape, and is built of bricks, and is the following size:—Thirteen feet nine inches on the front, and thirteen feet nine deep—a square. It is fifteen feet high, with a tiled roof. The ends of the two gables have elaborate sort of crow steps. The bricks stand out in every other step, about three inches, the result being a very pretty bit of brick work, and speaks clearly of the time when bricklayers laid many more bricks in a day’s work than they do now, and also took a greater pride in their work. The bottom part of the cote forms a shed for horses or cattle. This shed is ten feet high, so the walls of the cote are five feet up to the square, and with the gable ends provide room for a good few nesting places, but the brick walls are only-nine inches thick there, for the nesting boxes must have been fitted against them and probably were wooden squares on legs and lined with clay. These have now disappeared and the few pigeons that still are about must nest on the top of the walls. There is a string course just under the top, but it is not a very deep one, and another about the middle. The bricks have mellowed to a beautiful tint, and whole building is a very pleasing object. Major T. Huskinson says the date when it was built would be about the end of the seventeenth century. It forms a pretty object, and I must own to the soft impeachment that I envied the owner of it.

THE WOLLATON DOVECOTE.

WOLLATON COTE.

WOLLATON COTE.IT was on April 1st that I visited this dovecote. The wind blew cold, and from the east, and dull and grey was the sky. Buses took me all the way, changing in Nottingham. During the last few years this means of conveyance has increased to a wonderful extent, and now must be a serious drawback to railway dividends. But they are wonderfully convenient for getting about the country at a very moderate cost. After passing through Nottingham we soon came to the Park at Wollaton. It is over seven hundred acres in extent, with a lake of over twenty acres, well timbered, and with one of the grandest Tudor houses in England. Formerly there was a herd of white wild park cattle in it, and there still is a herd of deer. A great brick wall surrounds it, several miles in length, and as roads ran on two sides of it the late Lord Middleton had it seven feet high so that no one could when walking look over it. A short time after, when he was walking in it on the Wollaton road side, he saw some one looking over and could for some distance see his head above it. He was very much put out and gave orders that several more rows of bricks should at once be built on that part.

This was done, and shortly after he was told that the head and shoulders he had seen were those of a giant of over seven feet who was being shown at the Goose Fair at Nottingham, and who had that one morning been for a walk from Nottingham to Wollaton. This walk had caused his Lordship to spend a goodly number of pounds, which, if he had not been in the Park on that one morning, or sooner or later by a few minutes only, would have been saved—a pure bit of bad luck. The bus took me close to the cote which stands by itself in a fair sized grass paddock about the centre of the village and hard-by the interesting old Church, where I met Mr. Jordan, the late school master at Wollaton, who most kindly showed me the cote, and told me many interesting things pertaining to the village. There is no doubt about the time this pigeon cote was built, for on either side of the door are the initials F.W., and the bricks stand without doubt for Francis Willughby, who built the Hall in 1580. The bricks forming the initials are darker than the others in the wall, and still show clearly some distance away. The cote is nearly square, being fifteen feet from east to west, and seventeen feet six inches from north to south. The walls are twenty feet up to the square, and the roof is tiled. I was much struck with the door, which is only four feet high and two feet five inches wide. Most of the old cotes have small doors, so that if pigeons were stolen big hampers could not be used as the doors being small prevented large ones going through them. Over this door was a half circle of two rows of bricks standing proud of the wall, so making it a very ornamental entrance. In the days when it was built the name of the owner was spelt Willughby, without the “o,” and when that letter slipped in I know not, neither did the late Lady Middleton when I asked her. The walls are three feet three inches thick, and in the four are built five hundred and ninety nesting holes. These holes all have an entrance five inches high by five inches wide and go in thirteen inches and then have a roundish place on the left for the nest. Each row of nesting places has a course of bricks standing out below them for the pigeons to land on. Nesting places of this shape are called “L” shaped nests, but to me it looks as if that letter was the wrong way up. A short distance from the top of the wall are two string courses quite close together. This was perhaps to make sure of safety so that if the vermin succeeded in getting over one he would fail to survive the second, but I have doubts whether any sort of vermin could ever get up over the first one, for the walls are almost as smooth as the day when the bricks were laid, and the mortar is as hard as the bricks, but time has rotted the boards, so that I could not tell how many holes there were, but the one below it is still fairly sound, and there are ten entrance holes. There are no signs of an inside ladder, called a “potence,” which was used to get to the nesting places, but the wonderful oak beams are still sound and in good order and fit to carry another roof when it is wanted. The cote is still inhabited by a few pigeons, and of what I saw of their plumage they are descendants of the rock doves, which birds are known to be the ancestors of the dovecote race. There are many places on the rocky coasts of England, Ireland and Scotland where they live and breed in large quantities. These dovecote-bred birds in years past were the ones used for pigeon shooting matches, and were often called “blue rocks.” This trapshooting is not now lawful, and I cannot say I am sorry it has been stopped.

UPTON, NEAR SOUTHWELL,

COTE IN CHURCH TOWER.

UPTON CHURCH TOWER COTE.

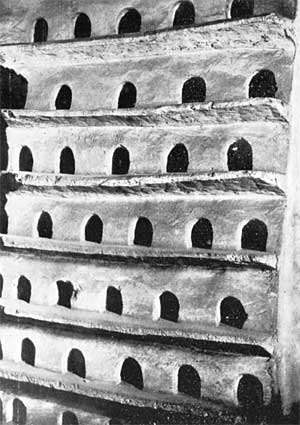

UPTON CHURCH TOWER COTE.APRIL 9th. Another wet morning, after a pouring night, but the old saying came true once more, “Rain before seven, fine before eleven,” and though it still poured hard at 10 a.m., by half-past it was lighter, and shortly after 11 a.m., though dull, grey, and cold, it ceased. So catching the eleven-thirty bus at Rainworth, I reached Upton at 12.25 a.m. I called at the Vicarage, and the Vicar, Rev. A. T. Randle, most kindly took me to the Church. It is of fair size, stands on the brow of the hill and overlooks the vale of Trent, a beautiful prospect. To the south-east I could see the tall spire of the fine Church at Newark-on-Trent, two hundred and sixty-eight feet high. There are, I think, only seven spires higher in England. I was much impressed with this grand sweep of country, a vale of rich pastures and rolling hills, through which the Trent winds like a silver ribbon. The tower is a most substantial one, and has withstood the storms of centuries, having been built in the reign of Henry III. It is beautifully topped with eight pinnacles, and a short spire rises in the centre of the square about twice as high as the outer ones. Passing through the Church, I came to the stairs, which are of stone, and on the south side of the tower and wind round a column. I counted thirty-six steps before I arrived and entered a squarish room about thirty feet above the Church floor. It measured nine feet from west to east, and twelve feet six inches from north to south. Its walls are three feet thick, and in it was the pigeon cote, or rather what had been the pigeon cote. On the walls were the nesting places that are now left, these numbering eighty-six. They are made of cement, and are fixed on the inside walls. Portions of those broken off show here and there, and I judged there must have been a good many more, they were well made, and varied little in size or shape. Under each row ran a ledge of three inches wide, these were for the pigeons to alight on. The entrance holes were about five inches and a half square and went in fifteen inches deep, but had no circular hole at end or side to nest in, still there was plenty of room, but none too much. The landing ledge ran under them from end to end of the wall, so there was not a separate landing step as in some cotes. Pigeon cotes in Church towers are rare, and Mr. Cooke, in his book on “Dovecotes,” only mentions a few, one in Gloucestershire and one in Herefordshire, and three or four others. I was pleased to think we had one in Nottinghamshire, and that I had seen it. I have to thank Mr. Summers, of Southwell, for the capital photograph of this cote. The nesting places being fixed on the walls, would lead us to suppose that they had been placed there after the tower was built, but there is nothing to prove this was so, but from the look of the mortar I should certainly say that they have been there for very many years, for there is a great difference between the mortar of Tudor days and that of these times; the mortar of that period is as hard, or harder, than the bricks of to-day. The Vicar, the Rev. A. T. Randle, has most kindly lent me a small account of the Church at Upton, written by the late Mr. Harry Gill, who was a great authority on archaeology, and who took much interest in the Churches of Notts. He gives in this notice an interesting account of the dovecote in the tower:

“A flight of thirty-six steps leads to a chamber occupying the full dimensions of the tower (ten feet square or so). This was evidently intended to be permanently occupied, for it contained a fireplace, and a hagioscope, so arranged that the recluse could see the altar while lying on his couch. It is worthy of note that the chamber at Upton has also been used as a “columbarium,” or dovecote. So far as I am aware, it is the only instance in the county of a Church tower being used for such a purpose. The fireplace and the hagioscope have been built up, and nesting holes composed chiefly of stucco were ranged round the walls in tiers twelve inches high. The vertical divisions fifteen inches from back to front are formed of thin, red bricks, or tiles, set on edge, and upon these divisions oak laths are laid to 'carry the stucco, of which each succeeding floor and ledge is made. The front of each compartment is pierced with an opening five inches wide and five inches high. Many of the nesting places were smashed when one of the bells fell some years back, and only eighty-seven complete ones remain. Several fine examples are to be found in Notts, but why a Church tower should come to be used for such a purpose is matter for conjecture.”