< Previous | Contents | Next >

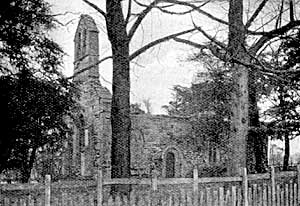

HAUGHTON CHAPEL. The ruins of the private chapel of the Earls of Clare.

Leaving Twyford Bridge we pass along the Bothamsall road for half a mile or more, cross The Duke's Drive, turn aside to the Old Hall Farm and, at a distance of 200 or 300 yards, reach the ruins of the private chapel of the Earls of Clare, interesting not because of any architectural beauty, but because it is the sleeping place of illustrious dead and a reminder of the vanished Hall. Haughton Hall stood upon the site of the farmhouse, but there is no remnant left save the moat, which denotes a baronial castle of considerable magnitude. Haughton Hall was built by Sir William Holles, a large merchant and lord mayor of London in the sixteenth century. His second son, the "good Sir William" was fond of display. At the coronation of Edward VI. he appeared at court with fifty followers in blue coats and badges, and he never went to the sessions at Retford without thirty "proper fellows" at his heels. The next in the Holies line was created Earl of Clare by James I. Beside partaking in the wars of his time, he fought a duel with Gervase Markham, in Sherwood Forest. He represented East Retford in parliament, and his second son, Denzil Holles, was one of the five M.P.'s whose arrest was attempted by Charles I. The fourth Earl of Clare was created Duke of Newcastle by William III. and Mary, as a reward for his devotion to their cause. When Clumber House was built (1792), Haughton Hall gradually fell into decay. The ruined chapel stands on the bank of a stream, overshadowed by fir trees and looking out upon a broad expanse of meadow-land.

The Mausoleum, Milton c.1910.

Leaving Haughton we proceed by the Duke's Drive to West Drayton, comparatively uninteresting, and then turn southward to Markham Clinton. Here there are two churches. The church of All Saints (for permission to view apply at the vicarage), occupies the summit of a hill between Milton and West Markham. It was built in 1833 by the Duke of Newcastle, partly as a mausoleum for the Newcastle family, to members of which there are several monuments. The old church at West Markham (key of Mr. Tindall) still exists, but is rapidly falling into decay, and is only used occasionally for burials. The floor is worn and broken, the walls discoloured, the altar, pulpit, seats and fittings are worm-eaten and mouldering. In the chancel is a recumbent stone statue of an ancient dame, and there are many ancient gravestones in the churchyard.

From West Markham we cross the Great North Road and, reserving Tuxford for a visit by rail, reach East Markham, a historic and picturesque village where large quantities of fruit are grown. The manor was for centuries in the possession of the Markham family. Sir John Markham, Judge of Common Pleas from 1396 to 1408, drew up the instrument for the deposition of Richard II. He died in 1409 in his native village and was buried in the chancel of the church. His son, Sir John, was Lord Chief Justice of England from 1462 to 1471. The church of St. John the Baptist (open daily), a fine Perpendicular building, and one of the finest in the district, has many features of interest. The tower, beautifully proportioned, is terminated by crocketed pinnacles.

From the top there is a fine view of Lincoln Cathedral and the surrounding country. The gargoyles are grotesque and elaborate. Within the church the following are notable features:— the rood staircase, a brass to the memory of Millicent Meryng (1419), the screen, apparently cut down and altered to meet the requirements of Laudian days; the pillars, clerestory windows, stained windows with armorial bearings in the south aisle, a window in memory of Mrs. Penrose (authoress of Mrs. Markham's History of England), an ancient poor-box, and the tomb of Judge Markham. In the year 1609, the plague broke out in Markham, which devastated the village and caused the removal of its market to Tuxford. There were 115 deaths.

The next village on our journey—some two miles from East Markham church—is Askham, pleasantly situated on a declivity. Hops were formerly grown here, but the cultivation has been abandoned. The fifteenth century church of St. Nicholas has recently been restored. In the restoration some curious niches in the walls were discovered. Two miles north-northeast we reach Headon-cum-Upton, passing through the hamlet of Upton before reaching Headon and the church, Headon Hall was a mansion situated in Headon park, west of the village. There were seven fine avenues converging on the Hall. Of these, one or two may still be traced, but the Hall has vanished and the grounds have been altered. The church of St. Peter (open all day), a fourteenth century building, contains a remarkable Jacobean pulpit with a canopy, and an Elizabethan oak chest. The register dates from 1566 and has been printed.

Headon is the last village we visit and our drive ends with the four miles into Retford. At about a mile from Headon the road crosses one of the remaining avenues of Headon Park.

(c) Places accessible by rail.

Barnby Moor is distant one mile from Sutton station and is a favourite place of residence. It is the point at which the Great North Road was deflected to pass through East Retford (see page 19). The old road by Sherwood Forest to Twyford Bridge can still be followed. A notable building is "Ye olde Bell," ivy-covered, many-gabled, adorned with flowers, with a cluster of tall old trees opposite, and extensive ornamental grounds. This was an old posting house, and in pre-railway days Queen Victoria—then Princess Victoria—stayed here one night when on her way with the Duchess of Kent to the musical festival at York. For some years the "Bell" was a private residence, but the revived road traffic of motor-cars has led to its re-opening as a roadside inn. It holds the official appointment of the Royal Automobile Club and the Road Club, and has an inspection pit. On the removal of the Fitzwilliam Hounds from Serlby (see page 11) they will be kennelled at Barnby Moor.

Blyth.

Blyth is the chief centre of population in a large parish with several hamlets. It is beautifully situated amid sylvan surroundings on the little river Ryton. At one time Blyth ranked amongst the great towns of Nottinghamshire. It held its own fairs and market, enjoyed many privileges, and was visited by members of reigning houses, archbishops and bishops, monks and priors, knights and nobles. Its market has long been abandoned, and the town has lost much of its former importance.

The town has many historical associations. It was the principal seat of Roger de Busli, who owned so many of the manors in this part of the country, and who founded and endowed the Benedictine Monastery. There was a tournament ground at Blyth—one of five only in all England—sanctioned and authorized by Richard I. in 1194, where the chivalry of mediaeval times was expressed in semi-military battles, encouraged by the smiles of love and beauty. Here tournaments were held in 1217 and 1252, and another was sanctioned by Henry III. in 1255, but abandoned on account of the perilous situation of Prince Edward in Gascony. The exact site of the tournament ground is not known. South of the town was a lepers' hospital, which upon the disappearance of leprosy, was used generally for the sick and poor. The site is now occupied by a farmhouse. Nearer to the town are the Spital Almshouses, in which the endowment partly remains.

Anciently the glory of Blyth was its Benedictine priory. The parish church of St. Mary and St. Martin (open daily) consisted in monastic times of south aisle only: this narrow Norman aisle was taken down and made nearly three times as wide to enable the brethren of the priory and the parishioners to worship separately under the same roof. At the present time the parish church consists, not merely of this widened south aisle, but also of the whole of what remains of the original priory church, and includes nave, with aisles, chancels, south porch, and a west tower of great beauty. The stately and lofty nave with its magnificent vaulting, and the narrow north aisle are part of the original Norman monastery, of which other fragments remain east of the present church. The church originally included transepts, a central tower, and an apsidal choir.

At the restoration in 1885, the wall at the east end of the nave was found to bear three ancient paintings-elaborate and beautiful—in fresco, descriptive of Time, Judgement and Eternity. The south aisle, as parish church, possessed its own chancel, and the fine screen still exists, bearing the painted figures of Saints Barbara, Stephen, Euphemia and Edmund the Martyr. There are many memorials, particularly to members of the Mellish family, who occupied for many years Blyth Hall. This is a fine mansion (with beautiful grounds) near to the church, built by Edward Mellish, who died in 1703. In the grounds the river Ryton forms a spacious island-studded lake. Altogether, Blyth is quite worthy of a visit, alike from the pleasantness of its situation, its historical associations, and on account of its noble church.

Hodsock (two miles south-west of Blyth) is in the parish of Blyth. The manor has passed through the hands of distinguished families, of whom the Cliftons are most notable. Sir Gervase Clifton (1587-1666), was seven times married. He was Lord High Steward of Retford, represented the borough in Parliament, and presented to the Corporation the smaller mace and several articles of plate (see page 26). From the Cliftons the estate passed to the Mellish family in 1765. Mr. William Mellish, who then lived at Blyth, was elected M.P. for Retford in 1741 and in 1747, and an incident recorded by Piercy, the historian of Retford, is worth repeating.

On the morning of the election, he brought two different, horses to Retford, one grey, and the other bay, by means of which he was to send information of the result; if chosen, the grey; if not, the bay. There being no opposition, he was elected, and immediately dispatched a messenger on the grey. His lady keeping a sharp look out, was so overcome that she fell into hysterics, and in the course of two or three days died.

Ranskill is another hamlet in the parish of Blyth, five and-a-half miles north of Retford on the Great North Road. It is notable as affording an instance of a successful village industry. There are works employing some forty hands and there are also maltkilns. There is a station at Ranskill, and this is the nearest approach to Blyth by rail.

Torworth is also a hamlet of Blyth parish, half a mile south of Ranskill. In 1820, two Roman urns were discovered here.