THE HISTORY OF LAXTON

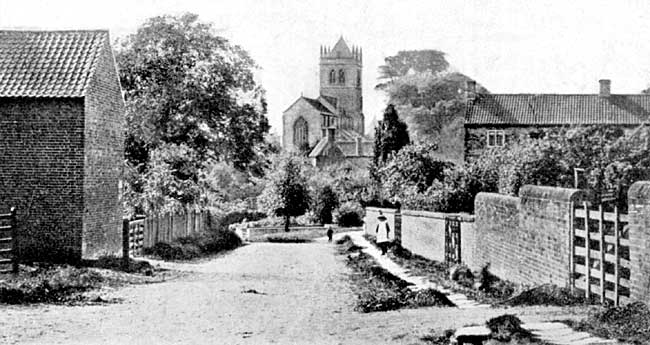

Laxton church from 'The Bar', c.1905.

LAXTON is unique among the villages of England to-day, because here and here only has the open field system of farming survived unchanged in its essentials since the days long before the Norman Conquest. But apart from this, the history of the village and of its lords is of exceptional interest, and the exhaustive researches of its late Vicar, the Rev. C. B. Collinson, have brought together a mass of information about it, which, with the very fine collection of manorial records in the possession of Earl Manvers, make it possible to give a coherent picture of the history and life of the place during the last 800 years.

I. THE DESCENT OF THE MANOR

Before the Norman Conquest, Laxton, also called Laxington, Lexington, and Lessington, was held by one Tochi, son of Outi, but it was granted by William the Conqueror to Geoffrey Alselin, a great Norman noble to whom were given, also, large estates in Nottinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Derbyshire, Yorkshire, and Lincolnshire. His only daughter married another Norman, Robert de Caux, who thus became Lord of the Manor of Laxton, and from them it descended without a break for more than 500 years, though four times in the female line, to the year 1618, when it passed by sale for the first time. The de Caux family held considerable estates, and in the twelfth century Laxton was the head of their barony. They built a castle in Laxton, on the fine site on the north side of the village, traces of which still remain, and the present church must have been begun in their time. They were Keepers of the Royal Forests in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, an office which was made hereditary in their family and which they held till 1287. In return for the administrative work of keeping order in the forests and seeing that the King's game was not poached 'the King pardoned him [Robert de Caux] the service of XII Knights' fees and granted him to take in the Forest hares, foxes, catts, greys, otters and squyr-reles, and the forfeture of the said beasts'. The family were good friends to the Church and made considerable gifts to the Priory of Haverholme, in Lincolnshire.

In 1186 the manor passed to an heiress, Matilda de Caux, who married, first, Ralph FitzStephen, Chamberlain to King Henry II, and, second, Adam de Birkin, one of a Yorkshire family holding estates in the West Riding. Adam's father, Peter de Birkin, had married Emma de Lasceles, also from the West Riding, and it is tempting to speculate that there are descendants of Adam de Birkin, good countryfolk, still living in Laxton to-day, who may have a common ancestor with the grandson of our Gracious King George V, somewhere in the twelfth century. Very little is known about Adam de Birkin, except that he made various grants of land in Yorkshire to the monks of Rievaulx, Pontefract, and Selby, and to the brethren of the hospital of St. Peter at York. To the monks of Pontefract he gave also 'a buck or doe yearly from his park of Birkin in commemoration of his soul on the day of St. John the Evangelist, and 2 old oak trees yearly for burning against Christmas time'.

Adam de Birkin, or his son John, had the doubtful privilege of entertaining King John at Laxton in 1213, when he was on one of his hunting expeditions in the Midlands. In the Pipe Roll there is an account for the expenses of the journey of the King and Queen'... and for two tuns of wine, 72/-, and for the expense of one veltrarius [a man who leads hounds] and six boarhounds at Lessington and eight greyhounds'. On another occasion in King John's reign, however, the men of Lexington had to pay Mm 100 pounds 'to have the King's peace and to spare their town from being burnt to the ground', though the cause of their offence is not stated. Another royal guest was King Henry III, in 1225.

In 1230 the manor of Laxton again passed to an heiress, Isabella de Birkin, who married Robert de Everingham, another Yorkshireman, from Everingham, near Selby, and in this family the lordship remained until the end of the fourteenth century. We know very little about Robert, but he or his son was Keeper of Sherwood Forest at the time when Robin Hood is said to have been there.

Robert's son, Adam de Everingham, was lord till 1280. He was an adherent of Simon de Montfort and probably he fought at the Battle of Evesham in 1265, for it is recorded that he was found with horses and arms against the King and Prince Edward. But in 1266 he was given a safe conduct to come to the King and treat for peace. His lands had been confiscated, but he was pardoned in 1268, though he had to pay a ransom of £100 for five years. After this he seems to have been a loyal subject, for he was summoned to perform military service against Lewelin, Prince of Wales, in 1277. He paid 40 marks for a licence to marry Isabella, the widow of Roger de Murley, but he lost the letters patent and had to get them renewed. He had, also, a licence to hunt the fox in Holderness, and he endowed a chantry at Everingham.

Everingham tombs in Laxton church.

The career of Adam's son, another Robert de Everingham, was brief and inglorious. He succeeded in 1280, aged 24, and married Alice de la Hyde. He was summoned to perform military service against the Welsh, and to the Parliament, at Shrewsbury, in 1283. But in 1287 he was deprived of his hereditary office of Keeper of the Forests for maladministration, was arrested and possibly died in prison. The Inquisitio Post Mortem, held to inquire into his property after his death in 1287, gives very full details of his manors and other land in Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, and Yorkshire; some, such as Laxton, held of the King in chief by knights' service, others held of other lords or churchmen, such as Everingham, which he held of the Archbishop of York by service of performing the office of butler in the house of the Archbishop on the day of his enthronement.

Robert's son, Adam, was only 7 years old when his father died, so he became a ward of the King, but his mother was allowed to keep him, though there were other guardians appointed. This Adam de Everingham, who lived till 1341, is in some ways the most interesting of all the lords of Laxton and more is known about him than any of the others.

In November 1290 King Edward I and Queen Eleanor stayed at Laxton for four or five days, when the Queen was very ill. She died at Harby, in Lincolnshire, the week after, and her heartbroken husband brought her body back to London, putting up a cross at every place where her body rested for the night on the journey.

Adam de Everingham married, first, Clarice, by whom he had five sons. He was made a Knight of the Bath in 1306, and after that he began to take a prominent part in public affairs. The reign of Edward II was a troublous time, with wars against the Scots and conspiracy and rebellion at home. From 1309 onwards Adam was summoned twelve times as a baron to Parliament, and frequently to perform military service against the Scots. He almost certainly fought at Bannockburn, as he was in Scotland that year.

During the rebellion of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, an Adam de Everingham was taken prisoner in arms against the King after the Battle of Boroughbridge, in 1322, and was delivered to the Sheriff of Yorkshire 'with a bed, 2 robes, and 2 horses, viz. one bay and the other iron gray'. But there is some doubt whether this was Adam of Laxton or his cousin of the same name from Yorkshire; he was pardoned in consideration of a heavy fine. After this not much more is known of his public life, but he went on military service to Guienne, and he may have been out of the country during Mortimer's rebellion and the deposition of Edward II.

He married his second wife, Margery, some time before 1329, and lived at home managing his estates. When Edward III sent round his writ of Quo Warranto, to find out by what warrant his barons claimed their feudal rights, Adam was able to establish that his ancestors had had 'from time out of mind', in his manors of Laxton and Shelford, 'waif, gallows, infangenthef, tumbrel, thew, view of frankpledge, and free warren in the demesne lands'. These were rights of administering summary justice.Adam was succeeded by his son, the third Adam de Everingham, who was born in 1311 and married Joan d'Eyville. He was on military service in France when his father died and was taken prisoner by the French, with his brother, but was ransomed and fought at the Battle of Crecy. While he was on service in France he fell ill with a fistula and could find no cure, but coming home he was cured by one John Ardern, author of a book called The Treatise of the Fistula, in which he describes how he healed 'Sir Adam de Everingham of Laxton in the Clay', and Adam lived thirty years after it. Very little is known of his later life. His eldest son, William, died before him, and his second son, Reginald, succeeded him in 1387.

Reginald was a Commissioner of Array for the County of Nottinghamshire and also a Commissioner to inquire into the 'enhancing and straitening of mills, weirs, stanks, stakes and kiddles' in the county. He married Agnes de Longvillers, but their son, Edmund, died before him, and after his death, in 1398, his inheritance passed to his two nieces, Joan, wife of Robert Waterton, and Katherine, wife of Sir John Etton.

Laxton fell to the share of Katherine Etton, and during the fifteenth century very little is known of its history or of its lords. Sir John Etton died in 1433, and his son, Miles, in 1438. Then Laxton passed once more to an heiress, Miles's daughter Isabella, who married John Roos, a Nottinghamshire squire, and in this family the manor remained for nearly 200 years, with one curious break.