PICTORIAL RECORDS.

We have previously mentioned the name of Mr. S. Clements, a gentleman who has performed a real service to such as are interested in the present subject, by making drawings and otherwise recording particulars of excavations brought to light during certain modern town improvements. The labour was performed in face of great difficulties, and the excavations themselves, as usual, were subsequently annihilated. Mr. Clements, besides affording us valuable information, very kindly allowed us to have the drawings photographed, the latter work being voluntarily undertaken by Mr. Edward Sutton, to whose kindness we are much indebted. To these, as definite and representative examples of Nottingham cave work, we will now devote some attention.

About a dozen years ago the Nottingham Corporation demolished the huge block of insanitary property immediately north of the Market Place, known as the "condemned area," across the site of which was subsequently formed the modern King and Queen-streets. The excavations for the new streets and property led to the exposure of perhaps the most wonderful and interesting series of caverns ever met with in the town, famous as it is for such works. Some had become disused; others not so. The site of the most noteworthy section, roughly speaking, is now marked by the line of the causeway in front of the Government buildings, so that, in making his survey, Mr. Clements had to acquire a "Government Permit." Its interesting and diversified character led Mr. Clements to execute a, sectional facsimile, to scale, and in the form of an eastern elevation. That gentleman has mounted this, in a glass case, accompanied by a suitable inscription, and has painted above it a background of forest, adding human figures, &o., with the idea of representing the state of affairs before the surface was built over. Most of Mr. Clement's drawings—13 in number, are associated with this neighbourhood, as the following list will show. We are indebted to Mr. W. Stevenson, the veteran authority on Nottingham history, for assistance in approximating the dates:—

Instructive details. A.D. 1100-1300.

Excavation in Wheeler-gate, destroyed 1895. (5).

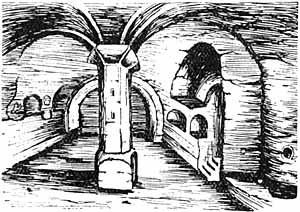

1. Great cave under Post Office, measuring 64ft. by 16ft., with three central pillars, south prospect, drawn 1893. Round Norman shaft in foreground, measuring 8ft. 6in. high, and 2in. less in circumference around centre. The arch in middle distance has moulding on the angle which, compared with arch-ribs in masonry, suggests the period as circa 1125.

2. This was drawn after the roof had been broken in, and is not quite clear in its details It appears to possess both semi-circular and pointed arches, and may, therefore, represent the transition period from Norman to early English, circa, 1175. Drawn, 1893. The great square pillar, which measured 6ft. 4in. in circumference, yet remains buried, as an isolated fragment, between the cellars.

3. Cave with three bricked-up semi-circular arches. The right-hand shaft or pillar has somewhat of the cushion-shape in the cap. Perhaps circa 1150. Drawn, 1893.

4. A remarkable example. Section of caves approached by perpendicular shafts; the latter, apparently, once fitted with staves, ladder fashion. The smaller shaft, besides having a narrow connection with the larger one, led to caves on a higher level that were entirely filled with debris. In the larger shaft, opposite to the entrance to caves, were rock recesses or niches, resembling doorways. This shaft was measured to a depth of 40 feet, below which it was filled with rubbish. No evidence of date. Sketched 1892. The site of this shaft, now entirely filled in, is under the causeway in front of the shop at the angle of King-street and Greyhound-street.

5. Cave showing acute pointed arches, moulded ribs, and a square pillar with mask on it, to give the idea of a terminal boss to the arch moulds. Circa 1250. Opened and destroyed during the widening of Wheeler-gate, 1895.

6. Cave, with recesses, &c., under the post-office, looking north, drawn 1894.

7. The same excavation, looking south. Drawn 1894.

8. Upper end of the same range, again looking south. Drawn 1894.

9. This cave was once drawn by Stretton, a local architect and antiquary, who flourished a century ago. It yet exists, under a shop on the Long-row, Mr. Clements' drawing being made in 1892. It has a central pillar (9ft. high), groined roof, &c., with much the appearance of a chapel, and measures 26ft. long and from 14ft. to 19ft. across. One might imagine an aumbrey, a piscina, and a credence. There is no indication of the pointed arch, but the roll-moulds, or sunken attached shafts, in the column and the well-defined arch-ribs are late enough for it. The cave is probably of the Transitional period, circa 1175.

10. A cave under the post-office, drawn 1894. This, though otherwise characterless, exhibits the rare feature of a "lip" or raised ridge of rock at the entrance, as though to keep out water. We have only noticed one other record of its occurrence.

11. Exterior of the Warser-gate rock-dwelling, in the ditch of the ancient town, as previously mentioned. Discovered 1890.

12. Interior of ditto, showing a round central column, with pronounced capital. Possibly referable to circa 1175.

13. This excavation, laid open and destroyed in Houndsgate in 1901, oblong in form, with central pillar, is the latest of the series, being worked in the Early English style, circa 1250, showing clustered column, and cable mouldings at the sides.

LOCAL APATHY

Members of archaeological societies visiting Nottingham invariably express disappointment at the excessively meagre character of our mediaeval architectural remains. Such paucity indeed is undeniable. What a strange reflection it is that, on the other hand, we are destroying almost daily examples of mediaeval handiwork and dwelling-places, of which single specimens, more favourably circumstanced, might be numbered among the sights of this or any town! As it is nobody gives them a second thought. We suffer from a plethora of riches.

As in past, so in modern times, strangers to the borough have displayed a far livelier appreciation of local rock-hewings than dwellers in our midst. The late Sir Stephen Glyn once travelled from Hawarden to spend a day with Mr. T. C. Hine, in inspecting the then accessible Nottingham rock habitations.

III.

THE PARK ROCK HOLES.

In justification of the avowed character of the present sketch, it is high time we devoted our attention more particularly to historical or documentary matters. We have said that the earliest Nottingham caverns were probably excavated in the face of the ancient cliffs limiting the Trent Valley, divisible into the three main sections of the Castle Rock, the Town Cliff, and Sneinton Hermitage. About a quarter of a mile westward of the Castle Rock, within the Park, occurs an isolated minor outcrop of the same cliff, not much above a hundred yards in length, and until recent years fronted by the river Leen. The Sneinton excavations practically never got beyond the initial or cliff stage, which sufficed for a village community. Our views of the process are further supported by the fact that the minor cliff under notice became, at an early date, honeycombed throughout its entire length, by a religious community. It included the various features of a great rock-hewn church, with aisles, such monastic features as kitchens, a dovecote, dormitories on a higher level, with rock-cut steps. &c., many of the apartments not being capable of identification. The fact of this prominent range of caverns being, in later centuries, open to the public, together with their remarkable character, secured for them a wide notoriety. This notoriety was largely due to the artistic and literary attention they received at the hands of Stukeley, Buck, Carter, and various other English topographical writers. In fact, they may safely be styled the most famous of all Nottingham excavations, although, as in other cases, much rubbish has been written in the endeavour to associate them with various periods, peoples, and uses. But it is not merely on account of notoriety that we here notice this range, of excavations. We first trace them as a possession of the adjacent priory of Lenton, founded between 1103 and 1108. Their antiquity is proved by the fact that Carter (vide Ancient Architecture) saw and sketched undeniable Norman details, now perished. Their principal importance to us, at the present time, however, is that they are definitely alluded to at an earlier date than any similar feature of old Nottingham. In the Pipe Roll of 29 Henry III. (1244-5), we find the King paying £6 1s. 8d. for the stipends of two Lenton monks, ministering in the Chapel of St. Mary, in the rock under the Castle. ("In stipendus duorum monachorum ministrantium in Capella St. Mariae de rupe subtus castrum de Notingham.") The same entry occurred on succeeding rolls for at least twenty years. In a valuation of the possessions of Lenton Priory, made in 1387, the "place called 'Le Roche'" was valued at 71s. 8d. yearly, beyond outgoings. In 1474 Edward IV. acquired the premises and appurtenant lands from the Prior of Lenton, to enlarge the Royal park, in exchange for the richly endowed Chapel of Tickhill, Yorkshire. It is then described as "The Chapel of St. Mary called 'The Roche,'" and the Prior agrees to provide a monk to say mass in the "Chapel of St. Mary of Roche," for the good estate of the King, &c. We do not know at what date divine service ceased to be performed, but probably before 1524-5, when it was reported that "the lodgings in the Parke called 'The Roche' is in dekay and ruyne, in timber, lede, tile, and glasse." In the time of the Civil War we learn that "the Roundheads destroyed a great part of the Rock Houses in the Park, under pretence of their abhorence of Popery." Hence our topographers and local historians were able only to depict a gradually decreasing ruin. After further vicissitudes, about 1874 what was left was enclosed in the grounds of a private residence. The existing remains, timeworn and characterless, have not only been taken care of, but have been, at great expense, artificially supported. They are yet accessible to the public, under certain conditions, and may still be considered among the most venerable and interesting of Nottingham rock excavations. Around them quite a literature has clustered.

BREWHOUSE YARD.

We have mentioned that Mr. Clement's drawings of local rock excavations, so far as they display architectural character, seem all referable to dates earlier than 1300. About the latter year our published and invaluable "Nottingham Borough Records" began to supply us with documentary references. A charter dated 1300-1 has to do with "a messuage that lies in the rock at the Milne Holes . . . . . . and it extends towards the mills of the Lord King's Castle towards the west at the end of the lane of the Milneholes." This clearly has reference to the rock dwelling at the foot of the Castle Rock (where the Castle Mills were situate), apparently in what is now called Brewhouse-yard. In 1313 we read of two cellars in the street called "Milneholes, which must also have been rock-cellars. It is remarkable how the workings in the cliffs hereabouts appear to have acquired the general name of holes, as exemplified by Milne Holes, Bugge Holes, Rock or Papists' Holes, and Mortimer's Hole. In 1336-7 there was a grant of "a messuage in the Milneholes, in the rock, near the tenement of Henry the Miller." On the same date there was another grant of "three messuages in the Milneholes. next the King's highway leading to the Mills of the King; and also of a messuage in the same street in the rock." There are also several 15th century allusions to these Milneholes.

In 1316 we read of "subterranean cellars" in the Saturday Market (on Long-row). In 1328, the grant of a plot of land in the Saturday Market expressly excepts "the rock-cellar underneath it." In 1334 we read of a cellar in the Daily Market, now known as Weekday Cross.

THE TAKING OF MORTIMER.

An Existing Excavation, Long-row. (9.)

On one occasion only has a "Nottingham rock excavation been associated with an important event in English history. We refer, of course, to the capture of Earl Mortimer (then living with the Queen in Nottingham Castle) by the young King Edward III., in 1330. from which circumstance arose the name of Mortimer's Hole. In a manuscript of about the reign of Henry VI., it is related that the assistance of William Eland, constable of the castle, was enlisted in connection with the scheme:— "Sir, quod the constabill, woll ye understonde that the yats of the castell both loken with lokys, and queen Isabell sent hidder by night for the kayes thereof, and they be layde under the chemsell of her beddis hede unto the morrow, and so I may not come into the castell by the yats no manner of wyse, but yet I know another weye by an aley that stretchith oute of the wards under the earthe into the castell, that goeth into the west, which aley queen Isabell, ne none of her meayne, ne the Mortimer, ne none of his companye, knowith it not. And so I shall lede you through the aley, and so ye shall come into the castell without aspyes of any man that beth your enemies," &c. But we need not dwell upon this well-known adventure, wherein two knights were slain, and which led to the life confinement of the queen mother, and to the termination of Mortimer's ambitious career on the gallows at Tyburn. It may, however, be mentioned that one who took part in it, Sir William Clinton, was an ancestor of the present owner of Nottingham Castle, viz., the Duke of Newcastle.

It may be appropriate here to touch upon the local tradition, current as early as the days of Leland and Camden, that David, King of Scots, after his capture at the battle of Nevill's Cross, was confined in a rock-hewn dungeon at Nottingham Castle, where he was reputed to have carved the story of Christ's Passion on the walls, &c. Deering, our town historian, while admitting that such carvings may have existed, throws discredit on their association with the Scottish monarch, while historical evidence is likewise against the story, which indeed is not believed nowadays. Some modern authorities incline to the view that the cell once pointed out—though no longer known—was really the cell or chapel of a religious recluse, with rudely engraved altar-piece, &c.

VAULTS, STORES, AND COMMON CAVES.

We seem to have only one early example of the word "vault" being applied to local rock excavations. As early as 1330 we have a reference to property in "Voutlane," the present Drury Hill, and a similar reference occurs in 1335. In the latter year, and in 1336, we have references to "Vouthalle" or "Vout Hall. This hall or house, which stood at the north-west angle of the lane in question, appears alway to have influenced its name. Deering informs us that Vout Hall, otherwise Vault Hall, "had its name from very large vaults which were under it, where in the time of the Staple of Calais great quantities of wool used to be lodged. In one of these vaults, in the reign of King Charles II., the Desenters privately met for the exercise of their religion."

Though we have little record of it, the fact is obvious that the local rock-hewings must have been widely used as store-places or warehouses. In all probability a rock-cavern is indicated in the will of Richard Colier, who in 1368 left "a storehouse for herrings, situate opposite Nottingham Bridge" (the Leen Bridge). The spot was appropriately, in or adjacent to the ancient Fisher-gate, where the town cliff runs.

In 1396 it was presented that "William Dynet has token and enclosed to himself from the common caves on the eastern side six feet in breadth, to wit, in that messuage in which Matthew Taylor dwells at the eastern end of the town of Nottingham, and to the great prejudice and damage of the aforesaid town." A charter of the year 1400 is concerned with "a piece of waste land, with a collar under the rock, lying in French Gate" (now called Castle Gate). In 1407 two men were complained against because they "throw cinders and dung outside the walls of the township in the common caves, to the blocking up of the said caves." Here again we cannot locate the "common caves." It would almost appear that they were entered from the town ditch. Were it not that we have no evidence of a south wall, the conditions seem to point to rubbish being thrown over the town cliff, and so obstructing traffic in some such caves as the Bugge Holes. In 1408 complaint was made that John Plumptre (founder of Plumptre Hospital), had "made a cave and placed a tree-trunk on the common ground."