< Previous | Contents | Next >

Kings and Archbishops constantly hunted in Sherwood Forest up to the 13th century. "Out of the bounds of the forest" (writes the Rev. R. H. Whitworth, F.R.H.S., in his History of Blidworth) "the Archbishop of York did hunt nine daies in the year: 3 against Christmas, 3 against Easter, and 3 against Whitsuntide, through the whole Wood of Blydworth, the Archbishop and his Canons and his men—and had their proper foresters and averies of hawks and pannage, and might do all things as if they were lawfully their own."

On October 24th, A.D. 1280, the King's pardon was granted to Nicholas del Ille, of Kirkby, for taking a stag in the wood of Bulwell," in the Forest of Shirewode" (W).

The forest was well stocked with deer in the reign of Henry VIII., for in 1532 that monarch had them counted, and at Papplewick the records show there were then 73 red deer, and 12 antlered deer; at Linby 30 red deer and 20 antlered. Complaints were made at that period that some of the gentry had been freely enclosing the King's forests, and among others reported for this offence was Sir Nicholas Strelley, who in A.D. 1515 had imparked at Linby 50 acres "within a certain paling and them so enclosed he keeps for rearing wild animals" (deer).

John Leland was sent through the country collecting information for Henry VIII., with orders to find out who might pay more tax to that free-spending monarch. Leland rode from Mansfield, and thus quaintly describes his journey:—"Soone after I entered, withyn the space of a mile or lesse, into the very thick of the woddy Forest of Sherwood, wher ys greate game of Deere, and so I rode a V. miles in the very woddy ground of the Forest, and so to a little poore streete, a thorougfare at the end of the wodde " (Papplewick). "A little or I came to the end of this wodde, I left about a quarter of a mile on the right hand, the ruins of Newstead, a priory of Chanons." (X)

That gifted and chatty writer, John Evelyn, travelled this way in A.D. 1654, and wrote: "We passed next through Sherewood Forest, accounted most extensive in England, then Paplewick, an uncomparable vista with a pretty lake nere it. Thence we saw Newstead Abbey, belonging to the Lord Biron, situated much like Fontainbleu in France, capable of being made a noble sete, accommodated as it is with brave woodes and streames. It has yet remaining the front of a glorious Abbey Church." Ten years later Evelyn was one of the Commissioners for the rebuilding of St. Paul's, and it may have been through his suggestion to Sir Christopher Wren that so many giant oaks were sent from Sherwood Forest to form beams in that magnificent church.

The remark of Thoroton in his Antiquities of Notts, (date 1677), that Bulwell Wood was "a waste in the Forest of Shirewood," in the reign of Henry III (A.D. 1216-1272), suggests that at one time Hucknall itself was within the forest boundary. He further remarked:—"The pleasant and glorious condition of Sherwood Forest is wonderfully declining, and soon there will not be enough wood to cover the bilberries which every summer were wont to be gathered by large numbers of people who gathered them and carried them about the country for sale."

There was a patch of land near the Hut at Newstead where the writer saw bilberries growing 30 years ago.

The Rev. Dr. Wylde, prebendary of Southwell, said his father, who died in 1787, aged 83, well remembered one continued wood from Mansfield to Nottingham, and the late Mrs. Rebecca Heath, of Hopping Hill Farm, Newstead, said in her father's time the Nottingham and Mansfield road was unfenced at Newstead, because their sheep used to stray in the forest towards Blidworth, and the tree branches interlaced over the highway.

The following cuttings from "The Postboy," a London newspaper, shows the perils travellers through the Forest had to undergo:—

Sherwood Forest Highwaymen.

"The Postboy,"

June 5th, 1700.

"There are two prisoners in Nottingham Gaol upon suspicion of being highwaymen, the one a young man between 20 and 30, and goes by the name of William Brewer, a middle-sized man, and wearing a perriwig; the other an ancient man about 50, and goes by the name of Robert Kibblewhite, a broad lusty man, and wearing a perriwig. The one rid on a sprightly grey mare about 14 hands high; the other upon a darkish bay mare, near 14 hands. There were two other persons in their company, but they made their escape. Any persons who have been robbed by such men, and have lost their mares, may have a sight of the persons at the Gaol in Nottingham, and of the mares at Warsop, in the same county."

Sherwood Forest Highwaymen.

"The Postboy,"

February 20th, 1706-7.

"They write from Ollerton, 12 miles from Nottingham, that a gentleman in his coach being robbed near that place by four highwaymen, sent his man after them in order to a discovery. The rogues perceiving he followed them, turned back and robbed him and beat him unmercifully. However, he raised the country, and by a 'hue and cry' found them at the Rufford Inn in Ollerton, where three were taken, and the fourth narrowly escaped out of a back window."

A writer in 1727 observed:—"The Forest of Shirewood supplies the town (Nottingham) with great store of wood for firing, though many burn pit-coal, which is offensive to the smell."

|

THE PARISH CHURCH.

What a crowd of memories cluster around the old village church! What a tide of human passion—joy, sorrow, comedy, tragedy, love, and hatred, have for centuries surged around its old grey, time-worn stones! There beneath the green turf, awaiting the crack of doom, lie remains of those actors in the drama of life, to whom Hucknall was their stage—Saxon, Norman, thane, feudal lord, priest, falconer, crusader, palmer, yeoman, shepherd, swineherd, husbandman, weaver, and collier—their full life-story known only to their Maker.

Domesday Book in 1086 makes no mention of a church here, but this is not conclusive evidence on the point, because the King's Commissioners had no orders to include churches in their survey, and the probability is that there was a wooden chapel attached to the Saxon Hall before the Conqueror came to England.

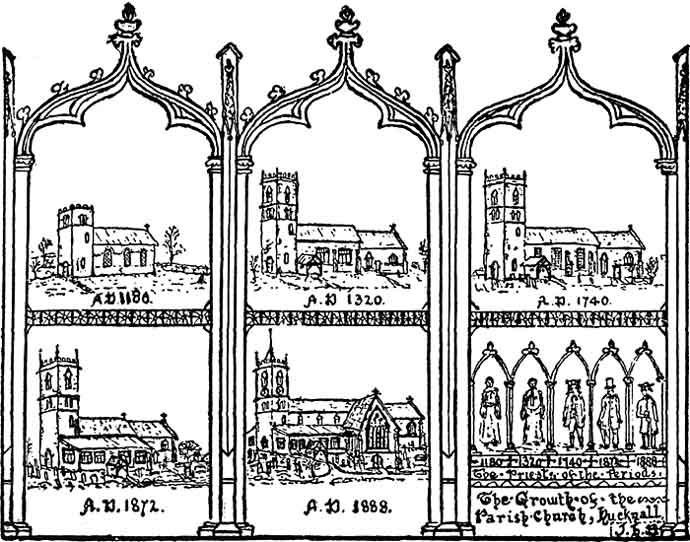

Fortunately the styles of architecture in vogue at different periods enable us to form an accurate idea of the growth of our venerable fabric. The late Mr. S. Dutton Walker, F.S.A., a well-known Nottingham architect, carefully examined the church in the year 1863, and gave the opinion (since corroborated by Mr. Harry Gill) that tower and nave were erected about the year 1180.

The Normans carried the tower up three stories with walls five feet thick, pierced with small windows. It was built of local stone, and faced with freestone, probably brought from the Gedling district. There is no evidence of the tower ever having been used for defensive purposes as many were. At the 1887-8 restoration it was found necessary to underpin and buttress this part of the fabric, because the 12th century builders had founded the northern wall on the loose stone ratchel, which in so many parts of the parish lies immediately under the surface soil. During the 1887 altera tions it was found that the 14th century builders had used mud instead of mortar in places when erecting the chancel. The Norman nave extended to the junction of the present transepts, and was constructed of thick walls pierced with small windows, through which light struggled in through shavings of horn, or lattices of wood and linen, or sheets of parchment (Y).

It is probable that the first roof was covered in with stone tiles, varying in size from 6 to 10 inches long, and from 4 to 6 inches wide. Quantities of these East Derbyshire blue lias tiles were found near the Churchyard wall, on the site of the Church Hall, in 1906, where they had probably been thrown when the nave roof was leaded in 1740. Messrs. St. John Hope, F.S.A., and T. M. Blagg, F.S.A., have examined these tiles, and after remarking on their resemblance to Roman tiles, agreed that they had been used by the early church builders, and had been fastened to the roof framework by the ties of deer antlers or wooden pegs.

Geoffrey Torkard was a large landowner in Hucknall at the time the church was founded, evidenced by the fact that in the year 1180 he executed a deed of gift to Lenton Abbey, and in 1189 he gave 120 acres of Hucknall land to Newstead Abbey; it is reasonable to assume, therefore, that he took a leading part in the founding of the Parish Church.

This view is strengthened by the fact that in A.D. 1199 a fine was levied between Geoffrey Torkard and Maud, his wife, and William Pitie, of two Knights' fees (about 400 acres) in Hucknall and Lambcote, whereof they all gave the Church of Hucknall and five bovats of land (75 acres) to Newstead Priory.

The fabric may have been dedicated in the first instance in honour of St. Mary Magdalene and All Saints (Z). For many years it was not known in the parish to whom the church was dedicated, so the Rev. George Otter, noting that the Village Feast was always observed in July near St. James' Day, concluded that St. James was the patron saint. Acting on this assumption James Street, on the old glebe, was so named 25 years ago, and when a daughter church was built at Butler's Hill in 1877, it was deemed appropriate to name it after St. John, brother of St. James. The late Rev. J. E. Phillips discovered the real name, "St. Mary Magdalene's Church," on an old map, and further enquiry proved this to be the true name.

If we could have looked inside the church soon after it was first built in the 12th century we should most likely have beheld scriptural scenes painted on the walls, but no pulpit or reading desk. The parson preached from the steps below the Communion Table. On the latter wax tapers were lit on great occasions, and a lamp lighted at night. It was the parson's duty to look to this lamp morning and night. The parsonage was built near the church (West and South-street corner), with ground attached, and near by were the dwellings of the poor people of the village.

The first important structural alteration in the fabric was made in the year 1320, when Thomas Torkard was vicar. The upper part of the tower was then built, the nave rebuilt, chancel, north aisle, and chapel at the east end thereof added, and a porch was erected on the south side. The north aisle appears to have been rebuilt about 1470, when John Leek (king's falconer), John Savage (a prominent county man), and John Kirketon (vicar), were important people in the parish. The present perpendicular windows replaced the 14th century lights in 1470. The north aisle wall was at one time pierced by two " low-sided windows," which afterwards were filled up with stonework. For a long time these low-sided windows, usually found at the junction of nave and chancel walls, were thought to have been made to enable lepers to gaze at the celebration of Mass, and to partake of the sacred food, but archaeologists have lately favoured the theory that their main use was for ventilating churches where all other windows were fast. The places occupied by these windows may be seen from the churchyard, immediately over the Jackson family tomb. The doorway in the north aisle wall, which was used for the egress of funeral processions, appears to have been built up at the same time as the low-sided windows.

A mutilated piscina of good type was found in the chapel wall in 1872, and may be seen there though the chapel is nowadays used as a clergy vestry and organ chamber.

Archaeological visitors to the church prior to the 1888 enlargement used to express surprise at the absence of a chancel arch, but this was demolished in 1840 because it was supposed to obstruct the sound of the singers in their gallery at the west end. The northeast pillar of the nave was concave in shape up to its adaptation for a pulpit in 1872, suggesting that the old rood screen was formerly approached by a spiral staircase supported by that pillar.

The porch has well withstood the vicissitudes of wear and weather; there it stands with its ancient barge-board intact as in the days of Thomas Torkard. Originally its roof was thatched, and in the 18th century a pair of gates kept strollers traversing the ever-open public pathway through the churchyard from loitering in the porch for purposes other than worship. The hole in the woodwork, into which the gate-bolt was shot, can still be seen in the centre of the boaxd. The porch was removed in 1872 to its present position, and re-erected stone by stone as it stood for over four centuries. Whilst dealing with the porch, it is opportune to notice the interesting old oaken door fashioned with axe and adze. There is no special ornament on it, but it is very massive and strong, and looks as if it will be useful for centuries. The lock is not so old as the door, for at first no lock was used, but a strong bar of wood used to be shot into a hole in the stonework on one side of an iron slot, and egress made from the church by the priests' doorway in the chancel. The porch doorstep up to 1872 was part of an ancient tomb slab.

< Previous | Contents | Next >

(W) Patent Rolls.

(X) The ancient road from Nottingham to Mansfield ran by the side of Bulwell

Forest and Bestwood Park, through. Papplewick and Newstead Park over the

footpath now known locally as "Up the ladder and down the wall." A

part of the old road may still be seen below Larch Farm. It was closed in

1760 by Act of Parliament, one argument for its closure being that many travellers

lost their way on it.

(Y) Gill's "Our Village Churches."

(Z) Extract from Will of John de Sutton, Vicar of Hucknall 1414-33, reads as

follows:—"I give my soul to God land Saint Mary and All Saints and

my body to be buried in the churchyard of Hokenell."