< Previous | Contents | Next >

Gateway to the Dukeries

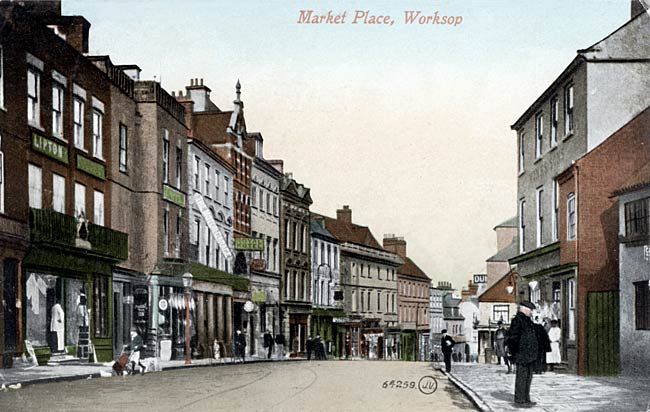

The Market Place, Worksop, c.1910.

WORKSOP. Its attractions are a noble church with grand Norman remains, the charming gatehouse of a lost priory, and its place on the fringe of the Forest as the northern gateway of the Dukeries. For the rest, it is a straggling old market town on the River Ryton, with the Chesterfield Canal passing through. Among its few old buildings is the Ship Inn by the marketplace, picturesque with gables and an overhanging room.

Within four miles of the town stand Welbeck and Clumber in their glorious parks; nearer still is Osberton Hall, a modern house in lovely grounds, with fine pictures and an almost unrivalled collection of British birds; and a mile away is its own great house, Worksop Manor, in a fine park.

The story of the Manor begins with the renowned John Talbot, first Earl of Shrewsbury, who built a house here in the 15th century.

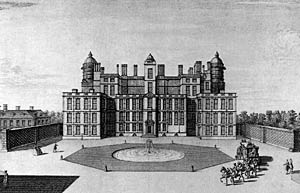

The north front of Worksop Manor in the 1750s.

The north front of Worksop Manor in the 1750s.His house was greatly enlarged by a later Talbot and his famous wife, Bess of Hardwick, and it was here with them that Mary Queen of Scots passed one of the most miserable spells of her imprisonment James the First was entertained here on his way to London for his crowning, and Horace Walpole came in 1756, five years before it was burned to the ground. The Duke of Norfolk, to whom the estate had passed, set 500 men to work on what he meant to be the finest house in England, but the death of his only son disturbed his plans when he had built 500 rooms, and in 1840 the Duke of Newcastle pulled most of it down, leaving enough of it to become the fine house we now see.

Worksop Priory gatehouse in 1998.

Workaday Worksop has crept up to the town's most precious possession, the lovely 14th century gatehouse of the Priory of Radford. Adorned with gables and buttresses and saints in canopied niches, it was guest-house as well as gatehouse, and has a big upper room with a fine window. The gateway itself has three fine arches, and its original black and white roof with moulded beams. It was probably built by Thomas, Lord Furnival; and towards the end of the century the monks added the charming porch to serve as a shrine for pilgrims, giving it a doorway on each side, a lovely window, a stairway to the upper room, and a very beautiful vaulted roof of delicate tracery, still in splendid condition.

As we stand under the gateway, one of the outer arches frames a charming view of a tall tapering cross on a flight of seven steps. It is restored with a new head, and was brought here from opposite the church gates, where in olden days Radford Fair was held round it; during the Commonwealth banns of marriage were published from the steps. The other end arch frames a delightful picture of the church, with its twin western towers about 90 feet high.

The Priory Church of Our Lady and St Cuthbert, Worksop in 2013.

© Copyright Tim Heaton and licensed for reuse under thisCreative Commons Licence.

The story of the priory church of St Mary and St Cuthbert goes back to early in the 12th century, when Sir William de Lovetot invited the Black Canons to found a monastery, granting them the small Norman church already here. The monks set to work to build a larger church, which consisted at first of a chancel, transepts, and one bay of the nave, round a central tower. By about 1160 the rest of the nave was completed and given for the use of the parish, but at the Dissolution Thomas Cromwell and his master Henry the Eighth destroyed the monastic part of what had become a noble church, leaving the nave, its aisles, and the two west towers.

So it has stood for centuries, a magnificent fragment of a great building which is being given back in our own day some of its lost glory. The grand Norman nave is 140 feet long and 60 wide, opening to aisles with stone vaulted roofs. Above the ten bays on each side is a handsome triforium and a clerestory of round-headed windows. The arches of the arcades and of the triforium are rich in ornament as clean-cut as if carved yesterday. The eastern bay of each arcade is different from the rest, for these two, with a fragment of the south transept, are the remains of the earliest work of the monks.

The big south porch (its beauty enhanced by the noble avenue of limes leading to it), has a stone-vaulted roof and a trefoiled niche in its east wall, and shelters a lovely doorway with a round arch on six shafts. It frames a beautiful door which is one of the precious things of the church, for, though patched here and there, it is the original door made of yew wood from Sherwood Forest late in the 12th or early in the 13th century. Its mass of exquisite ironwork, richly wrought in sweeping scrolls, is claimed to be the earliest example of its kind in England.

The deep west doorway, with shafts and zigzag ornament, has a lovely modern door with ironwork to match the old. A smaller doorway with a similar modern door opens to the north vestry, which had a beautiful vaulted roof, and was originally the parlour where the monks received their guests. Joining this north-west end of the church are slight remains of the priory cloisters. The northwest tower is about a hundred years older than its companion, and was raised when the other was built, both being finished in the 15th century. After the destructive work of Thomas Cromwell the ruins became a quarry of hewn and carved stone, from which houses, a farmhouse, and a water-mill were built. The mill and some of the buildings have been demolished, and a few years ago we found the stones of the old priory being used again in restoring the central crossing and the north transept. The south transept was rebuilt as a thanksgiving for the end of the Great War, and the beautiful lady chapel, with charming lancet windows, has been restored in memory of the men who did not come home. It is a memorial for a second time, for, in addition to the many names on the oak panelling of the fallen, there is an inscription cut in stone telling that the chapel was founded in the 13th century in memory of a Lord Furnival and of the Crusades in which he fell. His body was brought home by his brother and buried here. The architect of the restoration of the church and the gatehouse was Sir Harold Brakspear, his plans being carried on after his death by his son.

Lady Joan Furnival of 1395 lies in the nave, a battered alabaster figure wearing a lovely netted headdress, and a mantle over her long gown. Her husband, Sir Thomas Neville of 1406 (brother of the famous Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland), is one of the two battered knights lying on each side of the altar, both with legs missing below the knees. The other knight is a 14th century Furnival.

The south aisle has a 700-year-old piscina, the modern font has lovely foliage and medallions of the Four Evangelists, and the modern iron screenwork in the eastern bays of the arcades is delicately wrought with flowers. The chapel has an Elizabethan altar table, an oil painting of the Madonna and Child is by Domenichino, and the painting of the Holy Family is by Perugino. In a glass case is a skull, perhaps of one of the Sherwood Forest archers, still penetrated with the tip of an arrow which carried death in its flight. It was found near the porch last century, a grim and intimate touch with the life of the Forest in those far-off days. Big wooden figures of the Madonna and St Cuthbert are of interest for being the work of one of the congregation, who also carved the three figures of the Rood.

The custom of an old tenure is still observed at Worksop when a sovereign is crowned. The lord of the manor has to find a right-hand glove, and supports the king's right hand holding the sceptre.