< Previous | Contents | Next >

The King With His Jewelled Belt

St Patrick's church, Nuthall, in 2004.

NUTHALL. It has lost a great house like an Italian villa, but has kept a yew tree venerable enough to have seen most of the happenings in this place, growing fast along a busy highway. The tree may be nearly as old as the church, by which it spreads its shapely arms in a garden of flowers and firs and evergreens, the gateway shaded by magnificent beeches. The sturdy tower was made new in the 18th century, except for its base which is mainly 12th century and the oldest part of the church, its pointed arch of a little later time resting on the original sides.

Like most of the old stonework, the lovely doorway letting us in (adorned with medallions and heads of a king and a queen) comes from the end of the 14th century, the time of the nave arcade and the windows with flowing tracery. The 15th century east window has old glass showing the Crucifixion and heraldic shields; other windows have old shields and fragments. The medieval chancel screen (with modern gates), and the old part of the screen hiding the organ, enclosed the east end of the aisle till half a century ago.

On a floorstone of 1558 are the engraved portraits of Edward Boun, his wife, and five children. A rector's stone has a cross, a book, and a chalice, and fragments of other coffin stones are in the wall outside. In a founder's recess in the aisle lies the alabaster figure of Sir Robert Cokefield, a 14th century lord of the manor. He wears plate armour and a jewelled sword-belt; his head is on a crested helmet, a lion is at his feet, and his hands are at prayer. His family were lords of Nuthall for about 200 years; he may have known the old yew when it was young.

The Wonderful Beeches

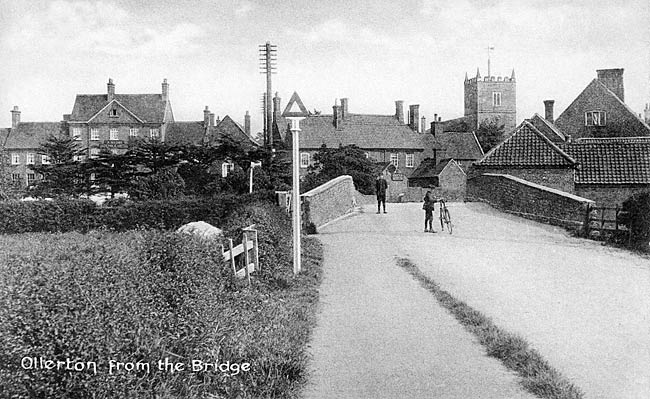

OLLERTON. New roads and a colliery are making their mark on this old village, but it still stands at the doorstep of the Dukeries and Robin Hood's Forest, and it has one of the finest natural monuments in England. The village is on the bank of the little River Maun, near its meeting with the Rainworth Water which has come a lovely journey through Rufford Park.

Where the road sets off to Bawtry, and the great stretch of Bilhagh begins, are the famous Ollerton Beeches, a superb bit of Sherwood Forest. It is like a nave and aisles not made with hands, the trees growing 50 feet apart, some with branches about 200 feet round. It was meant, we understand, to be the entrance to Thoresby, one of the three great houses of the Dukeries, but has come to have a glory of its own. We walked over a brown carpet of about 180,000 square feet, and we have seen few sights more impressive than these hundred giants so ancient and so still. From their dim twilight, their brown carpet, and their majestic trunks, we step into the loveliness and light of a thousand silver birches rising from a green carpet of ferns. On the brown carpet we look up to a roof like cathedral vaulting; on this green carpet it seemed to us, as once it seemed to Tom Hood, that birches with their slender tops were close against the sky.

Older than anything else in the village are the red bricks of the mill at the little bridge, by which is a garden of shrubs on an island made by the river as it turns the mill wheel; it is the Island of Remembrance, with a plain grey cross to 16 men who never came back.

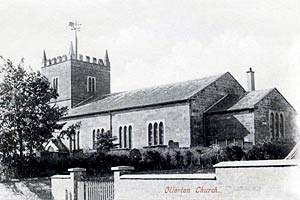

St Giles' church, Ollerton, c.1905.

It is sad that where Nature is so rich the church is so poor. It was made new in the 18th century, and has little except a stoutly bound oak chest with three tremendous old padlocks, and a modern screen made from the oaks of Sherwood Forest. There is a stone here to Thomas Markham who came home from battle in the Civil War to die in the Elizabethan house his father built where Ollerton Hall stands now. Thomas was the last of the men of this line of a famous Notts family.

One little story we heard which we shall not forget. In the ivy which was growing thickly round the dooway of the old inn when we called a rare spider lived for years. It lived and grew fat on thousands of flies, and it would allow itself to be seen without fear when it was the size of a small walnut. It was one of the minor sights of Ollerton until one day its friend the innkeeper, who had watched it for four years, showed it to a lady staying at the inn. It was the end of the Ollerton spider, for a little while afterwards the lady was seen to probe into the ivy, dash the spider to the ground, and crush it with her foot. Such things will some people do.