< Previous | Contents | Next >

A Poet's Thought of Earthly Things

Halloughton church in 2005.

Manor Farm, Halloughton, in 2005.

HALLOUGHTON. Just off the highway to Southwell, its few farms and dwellings straggle along a winding lane, all up and down and buried in orchards, going to the pretty Halloughton Dumble. The neat wayside church stands in a glorious company of elms and limes, silver birch and copper beech, an old yew, and a wide-spreading sycamore. It is said that Henry Kirke White loved to sit and dream in this charming seclusion. Here he may have sat and thought, as once he sat and wrote, that

Earthly things

Are but the transient pageants of an hour

And earthly pride is like the passing flower.

Though it was made new last century, the church keeps its original east end with two lancet windows. Its chief possession is the low 15th century screen, carved with tracery.

At one end of a farmhouse opposite the church is all that remains of a 14th century house associated with Southwell Minster, the home of a canon. Its stone walls are very thick, and some tracery is still left in one of its windows.

A Queen's Last Journey

HARBY. The memory of a queen clings to this small border village, for it was here that the gentle Eleanor of Castile died.

Here she came riding with Edward the First in September 1290 being detained by illness at the manor house of Richard de Weston while the king paid a round of visits. Here she died on the 27th of November with the king at her bedside, leaving him full of sorrow. "I loved her tenderly in her lifetime, and I do not cease to love her now she is dead," he wrote. From here they took her to Lincoln to be embalmed, and then by slow marches to Westminster Abbey, where she sleeps under a lovely tomb near the Coronation chair. The resting-place's on the solemn journey were marked by what have come to be known as Eleanor crosses, the last of which gave its name to Charing Cross, where a copy of this last one stands.

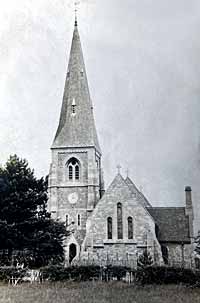

Harby church, c.1905.

In the field next to the churchyard is part of the moat which protected the manor house where she spent her last days, but nothing of the house is left. The old chapel in which the king founded a chantry to her memory has gone, save for two relics in the new stone church built near the old site. One is the plain Norman doorway opening to the vestry from outside; the other is the 14th century font. Here, too, are the only memorials Harby has to keep the queen's memory green, a small brass plate on the altar step telling us that she died here, and her little crowned figure in a niche above the tower doorway, with shields on each side of Castile and Leon, England and Ponthieu, as on her tomb at Westminster. Four tiles in the pavement near the brass inscription have similar shields.

The aisleless church is made into a cross by the vestry on one side, and the tower (crowned by a shingled spire rising 120 feet) on the other. A tiny old chest has a mass of carving on the front; the reredos of mosaic, set in the base of the east window, shows Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John and four angels; and the west window has figures of Hugh of Lincoln, Paulinus, and Augustine, and mothers bringing their children to Jesus.

Noble Trees and Old Masters

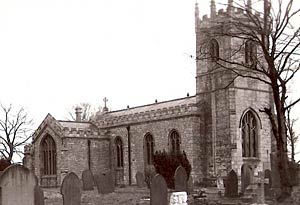

Harworth church in the 1920s.

HARWORTH. Its collieries are forgotten when we climb from the pleasant village to the church among trees and green fields, set on a little hill where the Roundheads are said to have mounted their guns to attack Tickhill Castle.

It came into Domesday Book, but, though fragments of Norman work remain, most of it was made new last century, when the Norman nave was pulled down, and transepts were added to give it the shape of a cross. The chancel was rebuilt in Norman fashion, but has still its lovely original arch, with unusual ornament and detached pillars, a very rare survival in two Norman sedilia, and the base of a Norman piscina given a new head. The fine south doorway, with its consecration cross, was built when the Norman style was passing into English.

All the walls are embattled, and eight pinnacles crown the tower, which has a modern west window in its 14th century base. Built into an outside wall is an ancient stone carved with a cross, and in a recess of another is a stone coffin.

Serlby Hall in the 1920s.

We have from the road by Serlby Park a splendid view of the red brick hall at the head of terraced lawns, its gaunt lines softened by a frame of dense woods. The road becomes here and there a glorious aisle of beeches, then runs with the sparkling River Ryton to a stone bridge, where the river flows on to the Idle and our way goes to the Great North Road.

Oaks and beeches are grouped about the park in stately grandeur, and beech avenues come close to the house and thread the lovely woods. An old heronry in the park has many nests. The hall has been the home of the Galways since the 18th century, and was built on the site of the older house about 1770. Among the pictures here are a portrait of Charles Stuart by Van Dyck, and another of Henry the Eighth. Almost covering the end of one room is a great painting by Daniel Mytens, showing Charles Stuart and Henrietta Maria with two horses and dogs, and the famous dwarf Jeffrey Hudson (who hopped out of a pie), trying to keep the dogs quiet. Attached to the hall is a chapel panelled in old oak, and in the gardens is a mound on which stood the church of a lost village.