< Previous | Contents | Next >

The Marvellous Scholar

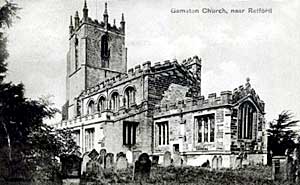

Gamston church, c.1905.

GAMSTON. Trim and pleasant with many trees, it lies between the Great North Road and the quiet River Idle, on the border of the old Sherwood Forest.

As we come from Elkesley, the all-embattled church with its line clerestory is a charming picture set in fields and woods, crowning a ridge which rises gently from the river. A round turret climbs at a corner of the nave. The massive tower, one of the finest in this countryside, has eight pinnacles 120 feet from the ground, and is a grand tribute to its early 15th century builder, who was perhaps Sir Nicholas Monboucher of 1385, owner of vast estates. The battered stone figure of a cross-legged knight lying in the aisle may be his.

Gamston church in 1982.

Though much of the church is 15th century, the nave arcade, some walling in the aisle, and the chancel arch (one of its corbels having a face with bared teeth) come from the end of the 13th century. In the chancel lies a priest in robes, his tonsured head resting on a cushion held by two angels; and built into the chancel wall is a coffin stone showing the head and shoulders of a priest recessed in a quatrefoil. A later rector was Charles Fynes Clinton, whose famous son, Henry Fynes Clinton, the classical scholar, was born here in 1781.

His scholarly passion was for Greek, and it is recorded that while at Oxford he went through 5223 pages of Greek literature. In later years he drew up a list of Greek and Latin authors and took great pains to obtain the quantity of their writings that have survived. He set himself the curious task of reducing their folio pages to a standard page of 1002 letters, and in eight years he read Greek literature filling over 33,000 of these standard pages.

He kept a literary journal in Latin or Greek until the day before he died. He considered that a scholar in Greek or Latin could be completely equipped for every purpose with a library of six or seven hundred volumes. Few men have ever had a more complete knowledge of Greek poets and prose writers. He himself declared that at Oxford in seven years and eight months he read through 69,322 verses of the Greek poets. He lived out the Psalmist's span of life and gave nearly every day of it to scholarship.

A Cricket Pitch Between Them

Gedling church, c.1905.

GEDLING. The fine view of the Trent Valley as we drop down the hill from Mapperley Plains is not to be forgotten, nor the charming picture of Gedling nestling below, with its church spire soaring above the trees.

The tower and its lofty spire is part of a beautiful old church built of stone from a local quarry, now a green hollow a mile away. It is one of the earliest examples of a tower and a spire of the same time, for both are about six centuries old. The spire is renowned for the pronounced bulging of its eight sides between its tiers of windows; in one of its image niches is a mailed knight, and below the battlements of the tower are 24 quaint heads. In a niche by the west window of the south aisle is a saint.

Though most of the church comes from between 1250 and 1340, there are traces of an earlier one in the lower walling of the chancel, and in a small window high up near the tower arch. A splendid stone-roofed porch leads us inside, where stately nave arcades of about 1300, below a 15th century clerestory, divide the nave and and aisles. The chancel, 50 feet long and half as wide, has beautiful lancets among its medieval windows, the east framing figures of Raphael and Michael as red-winged saints, and Mary and John by the Cross: it is the peace memorial. The sedilia and piscina, richly moulded, are 600 years old, as is the font. A coffin stone by the altar shows a deacon, perhaps of the 12th century, and another near the tower arch has the head and feet of a medieval priest. The fine pulpit was made from old carved bench-ends, and there is lovely modern craftsmanship in the chancel screen, the stalls, and the organ case with a figure of St Cecilia. The reredos and a silver hanging lamp are in memory of a rector's son who fell at Ypres.

On the hill from the Plains, not far from the church, is the delightful crescent of 12 Mary Elizabeth Almshouses with a steep roof and a Dutch gable at each end. There are lacy iron gates in the archways, and leaden window boxes embossed with vines; a rose garden is on the front terrace, and below is a sunken lawn. The charity was founded by the will of Mary Elizabeth Hardstaff, and the crescent has won for its architect, Mr T. C. Howitt (architect of the Nottingham Council House), the Architect's Bronze Medal.

In Gedling churchyard, which is like a rose-strewn garden, lie two great cricketers, their graves separated by about the length of a cricket pitch. They were Arthur Shrewsbury, whom Dr W. G. Grace described as the greatest batsman of his age, and his friend Alfred Shaw, who was known as Emperor of Bowlers.

Their friendship began in 1880, when they opened an athletic outfitter's shop in Nottingham. They went to Australia together four times, the great bowler and the great batsman sharing success and defeat. Shrewsbury's most brilliant year was 1887, when he scored 1653 runs, and before his last game in 1902 he had scored 60 centuries. A wonderful thing it was to see Shrewsbury, always cautious and patient, running up the scores, and Shaw knocking down the wickets with his untiring bowling.