< Previous | Contents | Next >

End of a War

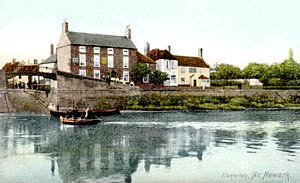

The River Trent at Fiskerton, c.1905.

FISKERTON. With its leafy road running along a bank of the Trent, its quay-like promenade above the river, and its pleasant houses with look-outs, it is a delightful little village, and fishermen love it well. The people go to the 18th century church at Morton.

It is all very peaceful now, but it looked out on a blood-stained sand over four centuries ago, and saw many men drowned in the river where the ferryman crosses. At East Stoke across the river was fought in 1487 the terrible battle which finally brought to an end the Wars of the Roses, when the army of Henry the Seventh routed the Yorkists with the pretender Lambert Simnel. The rebels were driven from the old Fosse Way towards the river meadows, down a steep track which has since been known as the Red Gutter because of the ghastly slaughter there. Looking on safely across the river, Fiskerton shared in the horror of the scene.

The Old Folk at Rest

Flawborough church in 2012.

© Copyright JThomas and licensed for reuse under thisCreative Commons Licence

FLAWBOROUGH. One of the smallest of Notts villages is this, where we see lovely views and hear that people never die. Into its panorama come Elston and Cotham, Shelton enshrined in trees, Sibthorpe and its fine dovecot, Thoroton's lovely tower, Belvoir Castle, and Bottesford's spire.

We can well believe the village is a good place for length of days, for, counting the ages on seven gravestones, we found the average to be 84. But someone found an answer as to why life even here must end, for another stone has the words:

It is no wonder we turn to clay

When rocks and stones and monuments decay.

The small church was made new a century ago, but a fine Norman doorway with zigzag in its arch lets us into the modern tower. The bowl of the font, enriched with interlaced arcading, is also Norman, and has a cover of about 1660. A plain chest is over 400 years old. The chancel has its old piscina and medieval tracery.

The Unknown Lady

FLEDBOROUGH. This home of a hundred folk who live in scattered dwellings has precious things to show to all who seek its lonely haunts.

Fledborough church in 2006.

At the end of a quiet lane leading to spacious Trent meadows we come suddenly upon a fine church full of interest, with a splendid chestnut and a lofty yew among the trees. By it is a deserted rectory with a score of chimney-pots, and near by is a pleasant manor farm. Clifton is over the river, spanned here by a railway bridge of about sixty arches.

So remote does it seem that we are not surprised to hear that it was a sort of Gretna Green in the 18th century, when a rector with the pleasant name of Sweetapple was willing to grant marriage licences to anyone. In the 19th century famous folk found their way here; Dr Arnold, the famous headmaster of Rugby, came to marry the rector's daughter in 1820, and nine years later came John Keble to bury the rector.

The church came into Domesday Book, but has nothing older than the low sturdy tower of about 1200. Except for the chancel and the 15th century porch, which are rebuilt, the rest of the church is 14th century. In the wall of the porch is an old sundial in pieces.

As the old panelled door opens, the light from beautiful windows shows up the lovely stone of walls and pillars, tinted with buff and green and rose. The arcades of the clerestoried nave have clustered pillars. There is an old stoup by the door, the font with a fine big bowl is 600 years old, the drain of a piscina, carved like a six-petalled flower, lies by the tower, and a pillar almsbox of 1684 says Remember the Poore.

Fragment of the Easter Sepulchre.

Built into the chancel wall are fragments of a 14th century Easter Sepulchre, their delicate carving showing three sleeping soldiers under canopies, and angels carrying Christ away. The biggest fragment has been a doorstep at the rectory.

A great possession of the church is the beautiful 14th century glass in some of the north aisle windows, with canopy tops and heraldic shields. (A few of the shields are new.) Its east window, which has a canopied niche in place of a middle light, is a charming frame for glass in delicate colours of pale gold and silver-green, showing St John, St Andrew, the Madonna, and a knight in armour; it is both old and new, the old setting the pattern for the new, and making together a window typical of those which once filled the church. Two fine panels of similar glass in another window have the Madonna and Child, and the figure of a woman with a book.

In the old lancet in the tower modern glass with St Gregory glows red, blue, green, and gold in the setting sun; and there is many-coloured glass in formal design in an aisle window given by the villagers as a thankoffering for their escape from cholera in 1849.

A very lovely thing is a 700-year-old coffin stone under the tower, carved with a cross which has a stem branching into a luxuriance of flowers, and a head adorned with bunches of leaves. Here lies the battered figure of a knight, his hands broken but still at prayer, his legsgone. He may be one of the Bassets, who were lords of the manor for 300 years, their property being confiscated by Parliament.

14th century effigy of a lady.

There are medieval gravestones to a rector, Hugh de Normanton, and to Dame de Lyseus, and in an outside recess stands the fine figure of a 14th century lady carved in stone. She is quite six feet and has a natural and charming expression. She wears a wimple, a long gown, and a mantle with graceful drapery caught up under her arms. She holds a heart in her hands, and from the cushions under her head, held by small angels, we know that she was originally lying down. She is the Unknown Lady of Fledborough, and has been here while 20 generations have come and gone. Near her is a 12th century stone coffin.