< Previous | Contents | Next >

A Home of the Cromwells

CROMWELL. With the old brick dwellings making a red patch on the Great North Road is the grey stone church in a churchyard surrounded by fine elms, a splendid beech, and a chestnut. Its name is its distinction. In the old house by the churchyard, once the rectory, are foundations which are said to be part of the old home of the Cromwells, of whom the last and most famous was Ralph, Lord Cromwell. Treasurer to Henry, the Sixth, Constable of Nottingham Castle and Keeper of Sherwood Forest, he was a man of wealth and a great builder. He built Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire, and the greater part of Wingfield Manor in Derbyshire.

Here sleep three members of a family who left their mark on the village and were rectors from the eve of the French Revolution to the eve of the Great War. The first was Charles Fynes Clinton, whose son Henry, a famous classical scholar, spent some of his boyhood here. The second was another Charles Fynes Clinton remembered for a book of sermons, and for editing the book on Roman chronology which his brother had begun. Henry Fynes Clinton followed them till 1911; he lies in the churchyard, the others in the chancel.

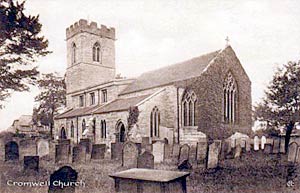

Cromwell church, c.1910.

A 15th century embattled tower crowns the pleasing little church, which was restored 60 years ago, when the 14th century arcade of two bays was opened out in the chancel, and the chapel built on old foundations. From the 13th century come the south doorway, the nave arcade, and some lancet windows. Among other medieval windows are two in the chancel with the graceful flowing tracery of the end of the 14th century, and in a tiny roundel of old glass is a rose. The low iron chancel screen with gates, wrought with delicate scrolls, was made in the village smithy in 1890.

We understand that all the men of Cromwell came home from the war, but that one died afterwards from wounds. It is one of the few villages without a memorial of the war.

The Carpenter's Whim

Cropwell Bishop church.

© Copyright David Hallam-Jones and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

CROPWELL BISHOP. It belongs to the byways, and in the days gone by the bells of its interesting old church were rung for an hour every Saturday night to guide the villagers home from Nottingham market.

The fine tower rising above the trees and red roofs is 15th century, the chancel is 14th (and restored), and the nave arcades with round pillars are 13th. The font (with a 17th century cover) and two piscinas are 600 years old, and from the same 14th century come most of the windows, except for the 500-year-old clerestory. The only colour in the windows are a few fragments of old glass, and the peace memorial window of St Nicholas with a ship, St George in armour, a soldier helping a comrade on the battlefield, and an angel with the crown of life.

In the nave are ten gnarled oak benches of about 1400, their poppyheads carved with flowers, faces, eagles, and little men with their legs doubled up. The chancel screen, a patchwork of old and new, has fragments of medieval tracery, faces of two men, and symbols of the Last Days in Jerusalem. Eight fearful stone grotesques support the lovely Tudor roof of the nave with its richly moulded beams and leafy bosses. It is odd that on a later beam than the rest the carpenter carved the date backwards, as if not quite sure how it would read from below: it runs 4671 instead of 1764. The oldest woodwork here is about 12 feet of wallplate from the middle of the 13th century.

In the great mill by the Grantham Canal plaster is worked from gypsum found near by. Cropwell Butler, a pleasant residential village a mile away, takes its name from the old family of Botiller.

The Greendale Oak

CUCKNEY. Here many ways meet on the edge of the Dukeries, with lovely views of their woodlands. Skirted by the River Poulter on its way to Welbeck and Clumber, it is pleasant with red-roofed houses in stone-walled gardens, set in haphazard array.

At a charming corner a shelving cedar stands facing an inn with cream walls and a swinging sign of the Greendale Oak. A mile and a half away, near Welbeck Abbey, is the famous tree to which the name belongs, so old that none can tell its age, its hollow trunk propped up but with life still flickering in it. It has a strange tale to tell. In 1724, as the result of a wager by the Earl of Oxford that he could drive a coach and four through one of his trees, an archway ten feet high was cut in the massive trunk, which was then about 35 feet round above the opening. One of the treasures of Welbeck is the Greendale Cabinet made of timber from this tree, inlaid with panels showing it in its prime, with the earl driving a coach and horses through the archway.

Cuckney church in 2002.

Into Cuckney's old story comes a Saxon knight who was allowed to keep land here after the Conquest in return for shoeing the king's palfrey when he came to Mansfield, being given a horse if he did his work well but forfeiting one of his own if he did not please. In the 12th century Thomas de Cuckney, founder of Welbeck Abbey, was lord of the manor, and a moated mound in the churchyard is said to be the site of his castle. The church was made new in his day, and treasures fine Norman remains.

Norman doorway.

It is a rare thing to find Norman work in a porch, but, though this porch was made new 700 years ago, it keeps an original string of Norman ornament which makes a dainty trimming for the top of the side walls, and also round the gable. A lovely Norman doorway, with zigzag and cable mouldings and a hood ending in grotesques, lets us into the church, where the long nave is divided from its aisle by an arcade of six round arches on pillars of varying shapes. Except for one round pillar which is earlier Norman, this arcade was built when the Norman style was changing to English, and the priest's doorway is of the same time.

From the 15th century come the top of the sturdy tower (on a 13th century base) and many of the windows. One frames a lovely Annunciation, and another, glowing red, blue, green and gold in memory of the men who did not come back, shows St George and St Alban with Our Lord.

There is an unusual piscina with worn ornament about 700 years old, and the broken remains of a fine stoup or font have been brought to church after being dug up in a garden. Three coffin stones form window-sills in an aisle, and part of another is in the nave floor. There is some old tracery in the tower screen.

A stone with a story lies in the middle of the chancel floor, so worn that its inscription is gone. It marks the resting-place of Robert Pierrepont, who became Earl of Kingston-upon-Hull in 1628 and was killed in the Civil War. One of his sons was for Parliament and one for the King, but the Earl tried to remain neutral and is reputed to have said, "When I take up arms with Parliament against the King, or with the King against Parliament, let a cannon ball divide me between them." Strangely enough it came to pass. After having at length declared himself on the side of the King, he was taken prisoner at Gainsborough, put in a boat to be taken to Hull, and was literally cut in two by a shot fired at the pinnace by Royalists on the bank.

A Knight and His Lady

DARLTON. Midway between Lincoln and Worksop, quiet little Darlton has wide views of the countryside, a small ancient church made partly new, and a house with something left of the days when it knew King John. The house is now a farm (called Kingshaugh), and part of its walls and some of the outbuildings are the ancient stone of King John's hunting lodge.

Darlton church in the 1920s.

Two lofty limes are guarding a 19th century lychgate, which frames a small 700-year-old lancet in the tower as we draw near. The tower is old and unbuttressed, and wears a new pyramid cap of red tiles. The great possession of the church is the lovely south doorway letting us in, built at the close of Norman days, and having a hood of fine moulding over a round arch resting on detached shafts. A tiny medieval arcade divides the nave from the aisle, and a big window a hundred years older lights the east wall. The old aumbry has flowers in the spandrels. A cup and its cover are Elizabethan.

Brass of knight and lady.

On the wall of the chancel are fine brass portraits of a knight and his lady, both with praying hands, and standing erect on grassy ground. The knight is in plate armour with a sword, his hair falling on to his shoulders; the lady has a long gown with an embroidered belt from which hangs a chain with an ornament, while from her pointed headdress two streamers fall to her elbows. They belong to about 1510, and are probably Sir William Mering and his wife.