The Thorough Dr Thoroton

CAR COLSTON. Not far from the Roman Fosse Way is this pretty village of many interests, its seclusion guarded by gates at the ends of the lanes that lead us to it. Cottages and little inn, fine houses and the old stocks, make a picture of old-world charm as they gather round the biggest green in the county. There is a handsome modern hall in Elizabethan style, and at the Screveton end of the village is part of the 17th century home of Dr Brunsell, who is said to have been a kinsman of Christopher Wren.

Here for many years lived Dr Robert Thoroton, whose famous Antiquities of Notts was published the year before he died in the village. He was born at Screveton in 1623, and after studying medicine in London he returned to his native county to practise. But his love was for antiquities, old churches, and old families, and he decided to interest himself more in the dead than in the living. The Civil War interrupted his work for a time, but after years of patient and careful study, during which he paid many assistants to gather information, he produced a magnificent work which was the first history of its kind and was long the chief authority of the county.

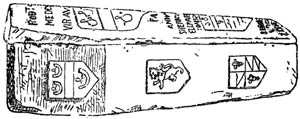

Sketch of Dr Thoroton's coffin, c.1900.

It is thought that in the farmhouse just beyond the church may be remains of the old Moryn Hall where Thoroton lived, and there are several reminders of him in the church. Here is the massive stone coffin he had made six years before he died, so that his body might rest undisturbed. He was buried in the coffin in the churchyard near the priest's doorway of the chancel, but when the churchyard was being lowered last century the coffin was taken up and placed in the church. Cut in the floor of the coffin is the inscription expressing his desire to lie undisturbed, and on the coped lid are his arms, his name, and the date of his death. The stone which marked his grave was found to be part of the old altar with two consecration crosses, and this also is in the church, where the Thoroton Society have set up a tablet to his memory.

On a buttress outside is a stone Dr Thoroton set up to mark his family's resting-place, telling that his grandfather Robert Thoroton was a loyal servant of King and Church, and that his great-grandfather Robert died of plague and was buried here.

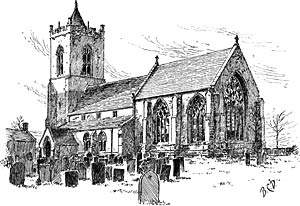

Car Colston church in the 1890s.

Round this fine little church runs an exceptional plinth moulding six feet high. The beautiful tower with slender belfry openings and a low pyramid roof belongs to the 13th and 15th centuries; other 13th century remains are the entrance to the south porch and the doorway within it which has an original door with later hinges. From the 14th century come the lofty nave arcades, the clerestory windows on the south, the north aisle windows, and its blocked doorway.

The glory of the church is its chancel, though its beauty is marred by the organ. Built in the 14th century, soon after the Black Death, it is typical of the fine work of this time in Notts, and has great gabled buttresses and lovely window tracery, the handsome sedilia and piscina being adorned with canopies, pinnacles, and finials. A grimacing man is peeping from one corner. The graceful altar rails are probably 17th century. There are a few old bench-ends, a poor-box 400 years old, parts of the old chancel screen in a dado, and carved Jacobean panels in the pulpit and a desk. The oldest relic is the round Norman font; one of our day is a wooden cross from a Flanders grave.

Ancient Treasure House

Carlton-in-Lindrick church in 2005.

CARLTON-IN-LINDRICK. It is two villages with one church. South Carlton lies in winding lanes, a delightful picture (as we come from Worksop) of red roofs and grey church tower peeping from a great bank of trees. North Carlton is on the busy highway, and on a little green between the two is an elegant peace memorial cross.

The church looks across the stone-walled road to stately beeches in the grounds of the hall, a great house in the classic style looking down on a lake fed by a stream which works a mill near by. There are old yews among the glorious trees in the churchyard, and from a mighty beech at its eastern end we have the prettiest view of the all-embattled and pinnacled church, framed by magnificent cedars and backed by limes and beeches.

There is still much Saxon work in the lovely tower of this church, which came into Domesday Book. The masonry of one stage is almost all fine herringbone. Its handsome west doorway is Norman, with zigzag among the mouldings, and three detached shafts on each side with foliage capitals; it was once the south doorway of the church, sheltered by the porch. The early Normans built the tower arch with enriched capitals, and the top storey and the fine buttresses reaching to the battlements are 15th century.

Interior of the nave of Carlton-in-Lindrick church in 2005.

As beautiful within as without, the church has a Norman arcade dividing the nave and north aisle. There is Norman work in the chancel arch, and on each side of a 13th century arch opening into the north chapel is a Norman light unglazed. One of the Norman treasures is the bowl of the font, with a band of scallop; another is a curious' tympanum over the vestry doorway, carved with two medallions under an arch crowned by a tiny cross.

The north clerestory windows and three other windows are 15th century. A charming 13th century lancet in the chapel is filled with a medley of medieval glass in fragments of yellow and gold, with red and blue in the border, and three medallions. The east window, shining with modern glass, has Our Lord in robes of white and gold, and angels looking down on eleven men of Galilee who have watched Him taken up out of their sight.

Much 15th or early 16th century work remains in the fine roofs of the nave and north aisle, and in their splendid gallery of nearly 40 carved bosses are the arms of the Fitzhughs and of Lord Dacre, the bull and the greyhound (badges of the Nevilles), the Five Wounds, a rose, a thunderbolt, a lion with human face and tongue hanging out, flowers, and a face looking like Henry the Eighth's.

In a case hangs a small medieval sculpture of the Trinity, with figures of Mary and John and six angels, two catching the blood from the Wounds, two with the Holy Grail. An old altar stone with three crosses lies in a recess, a 15th century gravestone has remains of a fine cross, and there is an old chest with three locks. A charming little treasure is the cover of the Litany, the leather patterned with flowers and crowns and animals, the metal bosses engraved with roses; it is believed to come from the time of Henry the Seventh.

Gentlemen, As You Pass By

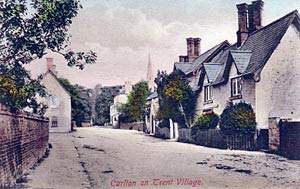

Main Street, Carlton-on-Trent, c.1905.

CARLTON-ON-TRENT. We found it all gabled and golden, shining among the trees, its church crowned by a prickly spire. A quiet oasis bypassed by the motor road, it has on one side the open Trent meadows where the ferryboat crosses the winding stream, and on the other it catches glimpses of the ceaseless traffic which now misses Carlton's stretch of the Great North Road, which enters the village as a lovely avenue of chestnuts.

The old inn, once astir with life, is now a golden farmhouse. The quaint wayside smithy is picturesque with a great brick horse-shoe round the entrance, painted black on golden walls and patterned to show the nails, its old rhyme beginning:

Gentlemen, as you pass by,

Upon this shoe pray cast an eye.

Carlton-on-Trent church, c.1910.

The stone church was built last century on the site of an old chapel of Norwell, of which the doorway is the only fragment left. It has a lofty tower and a graceful spire with two tiers of windows and a curious arrangement of rows of stone projecting like the spokes of a capstan. The altar table and two chests are 17th century, and a small old font, no longer used, looks like a huge egg cup with its bell-shaped bowl only 17 inches across. A window with a warrior at the foot of the Cross, and a brass engraved with arms, are in memory of George Brenton Laurie, who fought for his country in three wars and fell at last at Neuve Chapelle.