< Previous | Contents | Next >

The Story on the Pulpit

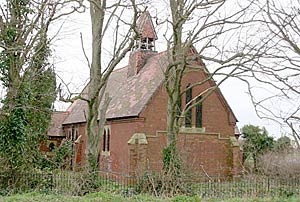

Bole church in the 1920s.

BOLE. It lies at the end of the road, with the Trent a mile away dividing the county from Lincolnshire. It has little but a simple church, yet its snow-white walls shelter two treasures worth finding. The tower, crowned by eight pinnacles, is 14th and 15th century, and a few old windows remain.

At each side of a brass on a window-sill, with an inscription to John Danby who died in 1400, is a tiny brass engraved with an angel and a bull. On the front of a pew near the pulpit is an old oak panel carved with the letter B and a tun, the rebus of the Bartons, who lived at Holme in the 15th century.

The royal arms are a curious amalgamation of those of Queen Anne and George the First, the king's white horse painted over the middle to save expense. The rose and thistle badge of Queen Anne remains, though she was the last sovereign to have a personal badge, and it should have been painted out.

One of the treasures here is a massive Norman font with double arcading round the eight sides of its bowl; the other is the pulpit, with four 17th century Flemish panels. Elaborately carved in relief, with eight figures and eight cherubs in the ornamental arcading, they tell the story of Esther and Haman in scenes in which 19 vivid figures take part. We see King Ahasuerus sitting under the canopy of his tent, and a man behind him with a halberd. Esther, who kneels before him, is attended by two maidens, and has come to use her influence on behalf of the Jews. We see Haman summoned to advise the king how to deal with a man he wishes tc honour, and Haman, thinking the honour is to fall on his own shoulders, suggesting that the royal crown and raiment be put on the man and that he should ride through the streets on the king's horse. The next scene shows Haman, with drooping countenance, leading the king's horse, on which rides his enemy Mordecai in the royal apparel. In the last picture the king and Esther are sitting at the banquet with Haman. Ahasuerus is handing a cup to Haman, who now looks mightily pleased at the honour shown him in being the only guest at the feast, little suspecting that soon he is to be hanged on the gallows he has prepared for Mordecai. The gallows is in the background, with Haman's tiny figure hanging from it.

The Saxon Track

BOTHAMSALL. It lies on the slope of a valley in which the Meden and the Maun flow side by side to become the River Idle, and, coming to it by the lane from the lovely road between Ollerton and Bawtry, there are two things to see.

One is Conjure Alders, a charming spot where the two rivers run as one, shaded by ash and alder trees, and spanned by a wooden bridge. The grassy track bringing us to it from the lane is one of the oldest ways in the county, and was carried over the river here by an ancient ford known by the Saxon name of Coningswath.

The other is a fine green mound by the wayside, known as Castle Hill. A dry moat runs all round it, splendid sycamores, beeches, oaks, and elms grow all over it, and a grand old oak rises from its hollowed crown. The site of an ancient camp or a fortified place, it looks out on a great panorama of fields, patches of woodland, and stretches of forest; and sees, close by, the little rivers in the valley, and the tower of Bothamsall peeping from a mantle of trees.

Bothamsall church in 2005.

© Copyright Richard Croft and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

It is a neat village. The 19th century church looks its best outside, with battlements and buttresses and a tower with a clock in memory of the men who did not come back. Among the few relics of the old church are two floorstones with crosses in the chancel, a fine 600-year-old font, and an old pewter flagon. In the vestry is the tomb of Henry Walters, who gave the church its silver paten of 1698. A floorstone marks the resting-place of Sir Charles Gregan-Craufurd who died in 1821 after a notable military career, and a brass plate with arms has an inscription to him and his wife.

The Solitary Tower

Bradmore church tower, c.1905.

BRADMORE. A neat little village on the road from Nottingham to Loughborough, it has a surprise for us as we climb from Bunny to what seems to be a church beckoning from the hilltop.

Here indeed we find an ancient tower and spire, but they are without a church, standing like a monument to the fire which destroyed the rest of it, as well as most of the village, over 200 years ago. For many years the solitary tower and spire, with remains of 14th century tracery in a window, stood useless and forsaken till it found a link with the world again in 1880, when a small mission room was built on to it.

The Ancient Sentinel

BRAMCOTE. It has much charm for those who find it, and magnificent views from its hilltop of villages and towns and streams, great houses and castles, in the wide Trent valley. We look from here into five counties.

The delightful Elizabethan manor house with its red brick walls and gables has made itself a fairyland, its old buildings transformed into charming dwellings round a rock garden with pools and flowers. The road by the old church leads to the modern Hall among the bluebell fields: it is now a school. Bramcote Hills, a fine house nestling in the trees beyond the Nottingham Road, is famous for its rhododendrons. Not far away we see at night the glowing fires from Stanton furnaces.

Tower of Bramcote old church.

A low 600-year-old tower in a closed churchyard is all that is left of the ancient church, though its 13th century font and some of its monuments are in the new church which took its place: it is 19th century, its pleasing spire a landmark. One memorial has a curious epitaph in which the first letters of the lines spell the name of Henry Hanley, who is said to have built the manor house about 1600. His memory is kept green by his almshouses in a street named after him in Nottingham.

To Bramcote belongs the famous Hemlock Stone, a natural phenomenon 30 feet high, rising from a green mound near Stapleford. It is a great mass of red sandstone rock which has resisted the action of rain and frost longer than man can tell, and its strange shape makes a curious feature of the landscape for miles round. For thousands of years nothing has disturbed this solitary sentinel, which is about 70 feet round and is said to weigh over 200 tons.

Links with Rome

BROUGH. Believed to have been the Roman station of Crocolana, it is now a hamlet on the Fosse Way, two miles from the Collinghams. Here have been found many Roman coins (called Brough pennies here) and remains of Roman dwellings with stone foundations and timber walls.

It is the tiny church of St Stephen, standing with a cluster of houses and a school, that brings us here today. Built of brick half a century ago, it is neat and trim and surprisingly pleasing, just a chancel and nave divided by an ironwork screen, and lit by 42 candles in candelabra wrought with leaves and scrolls. Among the saints shining in most of the windows are Catherine with her wheel, Agnes with a lamb, Margaret on a dragon. Stephen and Alban and Our Lord with a sphere are in the east window. It is curious to see in another General Gordon, wearing a red fez and holding his stick, standing astride a cannon. Very charming is the Christopher Whall glass in two lancets, showing the Madonna and Child in blue and white looking to St Hugh in mitre and rich green robes; a great swan at his side is trying to reach the golden chalice the saint holds. An angel at prayer crowns the cover of the font.

A bronze plaque by Sir George Frampton has figures of Fortitude in armour and Sympathy with a wreath, and an inscription to Thomas Smith Woolley telling us that he served this hamlet for 38 years and built the church and school.