< Previous | Contents | Next >

CHAPTER 9.

THE PILGRIM’S RETURN.

1811.

Byron returned to England on July 17, 1811, and was accorded a welcome by his two friends, Hobhouse and Dallas. The latter had been anticipating his return with great delight, and had been on the look out for his arrival for several days. Byron stayed at Reddish’s Hotel in St. James’ Street, and Dallas was a very early visitor. Dallas, who had already shown appreciation of Byron’s genius, was eager to learn what poetic fruits the pilgrimage had produced. He was told of a satire called Hints from Horace which awaited publication. Dallas was asked to see it through the press. He took it home with him, read it, and was bitterly disappointed. They breakfasted together next morning, and when Dallas asked if Hints from Horace was the only poem of the tour, Byron admitted somewhat reluctantly that he had written “a great many stanzas relative to the wanderings.” Dallas might see them if he wished—in fact, he might have them as a gift, and do what he liked with them. Dallas promised to do what he could with Hints from Horace, and went away with the manuscript of Childe Harold. He read it, and his enthusiasm knew no bounds. “You have written,” he said, in a letter to the author who was visiting Harrow, “one of the most delightful poems I have ever read. I have been so fascinated with Childe Harold that I have not been able to lay it down. I would almost pledge my life on its advancing the reputation of your poetical powers.”

When they met again, Byron was still unconvinced of its worth. “It is anything but poetry.” But he told Dallas he could do what he liked with it. Dallas therefore took steps to find a publisher. Miller, of Albermale Street, turned it down on account of the attack on Lord Elgin for his spoliation of the ruined buildings of Greece, whose publisher he happened to be. Eventually John Murray was chosen as publisher.

Byron had made up his mind to go to Newstead at the first opportunity. He wrote to his mother, who was there, signifying his intention of visiting her as soon as Hanson released him. Important legal business had to be transacted before he could leave London.

When he was making the final preparations for his journey to Newstead, he heard of his mother’s illness, and the next day news came that she was dead. A furious outburst of temper on receiving some bills which she thought excessive led to her having a stroke, and she died without regaining consciousness. Byron communicated the news of her death to his old Southwell friend, John Pigot. “My poor mother died yesterday! and I am on my way to attend her to the family vault . . . . I thank God her last moments were most tranquil . . . . Peace be with her!” Upon arriving at Newstead, the domestics gave him full details of his mother’s illness. In the evening he wrote to his friend Hobhouse: “There is to me something so incomprehensible in death, that I can neither speak nor think on the subject . . . . I have neither hopes nor fears beyond the grave.” This last statement seems quite inconsistent with his prayer for the peace of his mother’s soul.

He refused to attend his mother’s funeral. He stood at the door of the Abbey, and watched the procession move off towards the Ancient Church of Hucknall Torkard, where the family Vault had been opened for the interment, and then fell to a bout of sparring with his man-servant, Robert Rushton, who had accompanied him on his pilgrimage as far as Gibraltar, and with whom he used to box. It was a strange way of hiding his feelings. But he soon threw the gloves away, and withdrew alone for many hours.

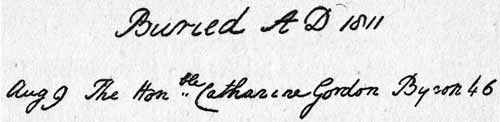

The following is the entry of his mother’s burial in the Church Register: —

Buried A.D. 1811.

Aug. 9, The Honble. Catharine Gordon Byron, 46.

He was to have sorrow on sorrow. Two days later he heard of the death of his friend, Charles Skinner Matthews, who was drowned while bathing in the Cam. “The blows followed each other so rapid,” he wrote to his friend Davies, “that I am yet stupid from the shock. Some curse hangs over me and mine. My mother lies a corpse in the house: one of my best friends is drowned in a ditch”—and not far away was the one who might have shared his burdens with him. How often must his thoughts have turned to Annesley! If only the dream of his earlier years had come true! Surely if he went to her, she would give him sympathy. Did he want it if she could not give him her love? A terrible sense of loneliness overwhelmed him again—“at twenty-three I am left alone. It is true I am young enough to begin again, but with whom can I retrace the laughing part of my life?” With whom? Could he detach himself from all the memories of the past, and begin life all over again? Could he find another Mary Chaworth? Was there another Mary Chaworth in the world for him to find?

His heart replied emphatically in the negative.

He certainly could not endure the agony of loneliness any longer—“I am growing nervous,” he wrote, “I can neither read, write, nor amuse myself—nor anyone else. My days are listless, and my nights restless. I have very seldom any society, and when I have, I run out of it.” What was he to do? He would leave Newstead and go to London.

|

|

| The Chancel of the Church of Hucknall Torkard. 1835. |

John Musters. |