< Previous | Contents | Next >

Introduction.

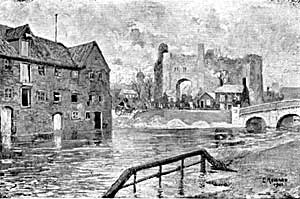

The Trent bridge.

NEWARK—the "New-Work," in distinction from some older work, probably Roman, either on the same site or m the immediate vicinity—owes its importance and the page it has filled in our country's history almost entirely to its geographical position on the route from the capital to the northern parts of the kingdom. In the Civil War Newark was known as "The Key of the North," and the persistence with which its possession was contested shows the value attached to it by Cavalier and Roundhead alike.

One of the best known of the old Roman highways— the Fosse Road— runs through the town, leading from the important cities of York and Lincoln to Leicester, Bath, and the midland and western parts of the country generally; while another ancient road, known as Sewstern Lane, leaving Ermine Street near Casterton, came direct to Newark, via Woolsthorpe-by-Belvoir and Long Bennington. This road, which for miles forms the boundary between Leicestershire and Lincolnshire, is now for the most part a wide grassy track, undisturbed by any wayfarer; its use in later times having been entirely supplanted by the loop road through Grantham, joining the old Sewstern Lane just outside Long Bennington village. This latter route became "The Great North Road" of the coaching days, and for the short period during which that mode of communication prevailed, Newark and its inns flourished apace, and were known to every traveller between London and Scotland. The construction of the main line of the Great Northern Railway still retained Newark in its old geographical position on the trunk road to the north; while the advent of the motor car has in some measure restored the importance of its roads and its hostelries, and again made them familiar to travellers from all quarters of the realm.

Another cause of the early importance of the town as a centre of traffic has been its situation on that great waterway, the river Trent. It has become usual for local quibblers to mystify visitors by telling them that Newark-upon-Trent is not on the Trent, but on the Devon (pronounced Deevon), and that the water which flows past its Castle walls is merely a canal. But this is only a quibble. The waters of the little river Devon, draining the Vale of Belvoir, do flow past the Castle, and the arm of the Trent into which they run, and on which Newark stands, has been canalised, the wider bed of the river dividing from this at Averham Weir and flowing round by Kelharn and Muskham bridges, 1½ miles away, to re-unite below the town at Crankley Point. But, nevertheless, the water by the Castle is the Trent, and always has been the Trent, and is so called in all mediaeval deeds and charters (which it would not have been, had there been no connection between it and the river above Averham Weir), and was indeed the main stream of the river until the 16th century, when Mr. Sutton, of Averham, cut away part of the bank to get more water for certain mills he had, to the shortage of those at Newark; which involved Mr. Sutton in a law suit with the bui'gesses, whereby he was compelled to construct a weir, to ensure the Newarkers water sufficient to work their mills and float their boats.

Flood time.

This river Trent then, was another great means of Newark's early prosperity. In days when the wide Roman roads had long been neglected, when wheeled traffic had almost ceased to exist in the land, and strings of pack-horses were the only means for conveying merchandise to many an inland town, the possession of a navigable river was to an English borough what a railway line is to the colonial townlet of to-day—it became an inland port and a distributing centre for all the commodities of the Middle Ages.

The member roll of the local Guild of the Holy Trinity, and many another old-time record, show the intercourse and connection which existed between Newark and Boston, the great seaport of the mediaeval Midlands. Down the Trent, up the Foss-dyke to Lincoln, and down the Witham, trailed slow barges (hauled by lads and women, horses were then too valuable), laden with the wool which was our chief English export. At Boston this was transferred to foreign merchantmen and conveyed to Calais, while the river craft returned to Newark, bearing wines and cloth and other manufactured products of France and Flanders, and spices of the East which merchants of Venice and Genoa had sent to northern Europe. Previous to 1390, a portion of this wool traffic went from Newark by way of Hull, as well as Boston, and was exported direct to Bruges and Antwerp; but after that date, in order the easier to collect the customs and to check the weights, Calais was made the sole receiving port, and all Newark wool had to go there by way of Boston only.

In more modern days, in the last quarter of the eighteenth and in the first half of the nineteenth century—the times immediately preceding the advent of railways—water again became the great means in England for moving bulky goods from place to place, and a net-work of canals was constructed throughout the country, which placed Newark in communication with all parts. Newark grain and malt and flour were exported by boat to Nottingham, Leicester, Derby, Manchester, and Hull, the boats returning with coal, salt, timber, and other goods. The traffic on the river to-day is still of considerable dimensions, and its competition insures to Newark the blessing of low freight rates by rail. Plaster-of-Paris from the local gypsum beds is one of the chief exports, and the boats return with barley for the maltings, maize, and agricultural feeding stuffs.

Thus, though neither a county capital nor a cathedral city, Newark, more than most towns that are neither, and some towns that are both, has much to interest those who care for the past. Here died King John in 1216. Four miles away, in 1487, the battle of Stoke Field finished the Wars of the Eoses, and formed the land-mark where, for England, the Middle Ages ended and the Renaissance began. Hither came King James in 1603 on his way to assume the Crown of England, and hither, forty-two years later, came his son, King Charles, to surrender that crown and his own person to the Scots army in leaguer before the Castle. Thrice besieged, yet never taken, Newark well earned its title of the "Loyal Borough," by which it is always alluded to in public grants and proclamations.

Garrisoned for the King at the very outbreak of the Great Rebellion, once relieved by Rupert's fiery cavalry, once by a force under Sir Marmaduke Langdale, the garrison had been finally left to its own resources, the King's Cause having waxed so desperate that he was powerless to send further succour.

Closely invested, by works which may still be traced, for six months the Cavaliers held their own in a siege replete with gallant incidents, though under ever-increasing privations, and only surrendered when commanded to do so by a written order from the King himself. Even then the burgesses, headed by their Mayor, on their knees besought Lord Bellasis, the Governor, "to trust God and sally," instead of quietly yielding up the town. Although Lord Bellasis had to obey orders and surrender, he marched out with all the honours of war; officers and men alike retaining their swords, horses, and baggage, with liberty to depart unmolested whither each pleased.

In the parish church, Jeremy Taylor, master of eloquent English, is said to have once preached a sermon. Dr. John Blow, the "Father of English Music," who was a native of the town, was baptised in the church in 1649, and doubtless first learnt music as a choir boy of the Magnus Song School Foundation. In later times Lord Byron came here frequently from his mother's house at Southwell, staying at the Clinton (then the Kingston) Arms, and superintending the printing of his first volumes of poems (1806-8) at Ridge's shop, the building at the north corner of Bridge Street and the Market Place. From the windows of that same Clinton Arms, Mr. Gladstone addressed the burgesses when standing for Parliament in 1832, Newark being his first constituency. Charles Lamb stayed here during the election of 1829, brought by a friend of the candidate, for whom he wrote some election squibs and ballads, some of the original handbills of which may be occasionally picked up in the town by enthusiastic collectors of "Eliana." At the Grammar School, the late Reynolds Hole, Dean of Rochester, friend of Leech and Thackeray, and lover of wit and roses, spent his school days. And many other well-known men and minds, too numerous to detail here, have at some time of their lives been associated with Newark, crowding its streets with memories of the past, charging its atmosphere with many reminiscences, ghosts of great figures in history or literature.