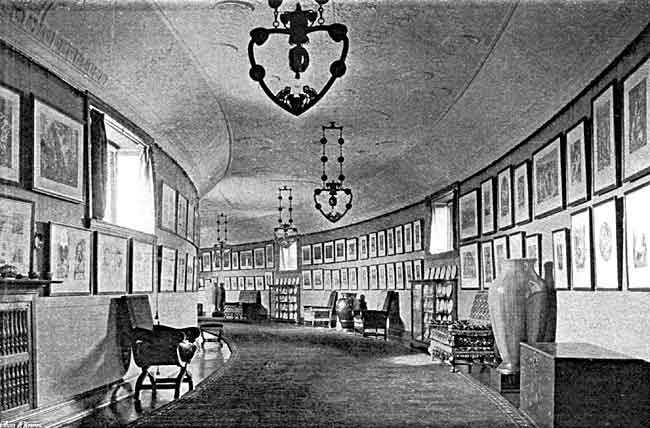

The Gallery of Prints.

The Keppels and the Bentincks mark for our peerage the age in which William of Orange came over to preserve the liberties of a nation which gave him but grudging gratitude. Two Dutch adventurers, as discontented English politicians would miscall them, were William's most trusted friends. Of Arnold Joost van Keppel, a lad born of a great house of the Guelderland nobility, and William Bentinck, a younger son of a gentle family at Overyssel, King William made two English earls and Knights of the Garter. The Keppels, although their ancestor went home to Holland after the King's death, have since been English of the English, and their house, founded by a soldier who was at Ramillies and Oudenarde, has bred us many famous fighting men, and still holds the earldom of Albemarle. But the Bentincks have climbed higher: their marriages have set them amongst the great governing families of the country.

Our first Bentinck might thank his handsome face for his first advancement. He became page to the Prince of Orange, and gentleman of his bedchamber, " the best servant I have known in princes' or private families," wrote Sir William Temple, to whom Bentinck's master told the tale of how when at death's door with small-pox "in sixteen days and nights he never called once that he was not answered by Monsieur Bentinck as if he had been awake." Bentinck had no quality of a great statesman, but he was loyal and steadfast. Our envious countrymen saw a Dutchman's boorishness in his carriage, but the courtiers of the Grand Monarque, no mean judges of a gallant gentleman, had nothing but admiration for the ambassador whose splendid equipage recalled the cloth of gold embassy of Buckingham. As a soldier he showed a Dutchman's stolid courage, riding beside his King at the Boyne Water with the Dutch horse guards, and at Landen, where one ball cut a curl off the King's peruke, another pierced his broad sleeve, and a third grazed his side.. His rewards were rich and many, a grant of the royal house and demesnes of Theobalds being made to him after the jealous Commons had protested against a vast endowment of Welsh lands. For his first wife he had Anne Villiers, a cousin of another ducal family founded by a handsome page, and, like her husband, one of the household of Orange, being a maid of honour to the Princess Mary. At the rise of Keppel as Court favourite the Earl of Portland, "cold and dry who seemed to have the art of creating many enemies to himself and not one friend," withdrew himself from the Court, but when William lay gasping in asthma upon his death-bed it was for his old servant Portland that he asked with his last spoken word, and he died with Portland at his bedside. In the next generation the earldom of Portland became a dukedom for Henry Bentinck, who died Captain-General and Governor of Jamaica, and the Welbeck estates came in by the marriage of the second Duke with the Lady Margaret Cavendish Harley. The third Duke was Prime Minister in 1783 and 1807, joining Pitt's Administration in the days of the French Revolution; and the sixth duke, now lord of Welbeck, is his great-grandson, having succeeded in 1879 on the death of his cousin, through whose surviving sister the great London estates of the Bentincks have passed to Lord Howard de Walden.

The house of Welbeck Abbey has been a-making in various styles since its Cavendish owner began his work upon it in the reign of James I., building in some part of the old structure of the abbots of Welbeck. It is a sombre pile, massive and ugly in many styles. The west front has battled parapets, and a great square tower from which the Duke may display his banner, while the east front, rising from a broad terrace over the lawns towards the lake, has a gabled roof. The south front has for its ideal the Italian villa with balustered parapets into which so many great English homes have changed themselves. Many additions were made by the late Duke, the most curious being the subterranean tunnels which run in all directions, and the large rooms constructed underground. Through one tunnel is reached a riding school, 385ft. long and 112ft. wide. The great ballroom, unfinished at the death of the fifth Duke, is seen in one of our pictures, with its wonderful floor of polished oak and its walls, now hung with several scores of old paintings.

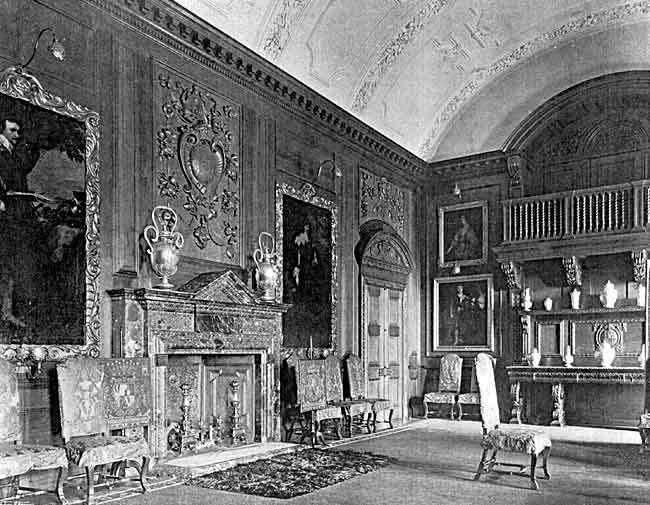

Part of the Dining-Room.

The stables are amongst the most remarkable in the kingdom, as befits the house of one who has been twice Master of the Horse, the descendant of that mirror of horse-masiers, the Duke of Newcastle, and here a hundred horses may have their stalls. The present Duke's winnings upon the Turf are not far away, in the shape of a row of almshouses.

But the contents of Welbeck are more remarkable than the house. The pictures', and above all the portraits by old English and foreign masters, areas notable for their number as their quality. Here is a famous Queen Elizabeth of Mark Gheeraedts, and here, in the dining-room, is that wonderful Van Dyck, the boy Charles, Prince of Wales, which was last seen in London amongst the royal portraits at the New Gallery. A brown and round-faced boy, with straight hair falling upon his forehead, Charles is painted in half armour, the tasses meeting riding boots of soft leather. On a mass of stone at his left hand rests his helmet with red and white plumes, and the beautilul hands of the boy play with the wheel-lock of a pistol. The boyhood of the elder Charles is recorded here also by the sad face over a ruff ot a child in long skirts of green velvet, a child carrying a little dag or gun, his greyhound running beside him. Here is the first of the Portlands, a somewhat hard-faced Kneller, a contrast with the triumphant male beauty of the portrait which Hyacinthe Rigaud painted of the popular peace envoy. Our picture shows the Reynolds portrait of the third Duke, a Georgian statesman, seated before his papers, in velvet coat, white stockings, and little wig, his lace-ruffled hand at his chin.

The many lines of heirs which have met in the house of Portland explain this gathering of Holbein, Janssen, and Mytens, Van Dyck, Lely and Kneller, Dahl ana Richardson, Reynolds and Gainsborough, West and Lawrence. Portraits of Noels and Wriothesleys came in by the first Duke's marriage. Harleys, Cavendishes, and Holleses are here through the second Duke's match. Beside these are Talbots and Veres, Pierreponts and Villierses, the last including a portrait of George Villiers, the favourite, painted when a beardless lad. In our picture of the dining-room Van Dyck's picture of Strafford in his armour, booted and spurred, lowering brows and keen face over a plain white collar, is flanked on the other side of the mantel-piece by another Van Dyck, the portrait of the Duke of Newcastle, all cavalier, from the love-lock on his left shoulder to his rosetted shoes. Beside the fireplace below are seen two old screens of needlework of the arms of John Holies, second Earl of Clare. The tall picture by Mytens of a lady in black, with dark hair brushed back from her forehead, a platter-shaped ruff, and long cambric cuffs, is that of the Duke of Newcastle's first wife, Elizabeth Basset of Blore.