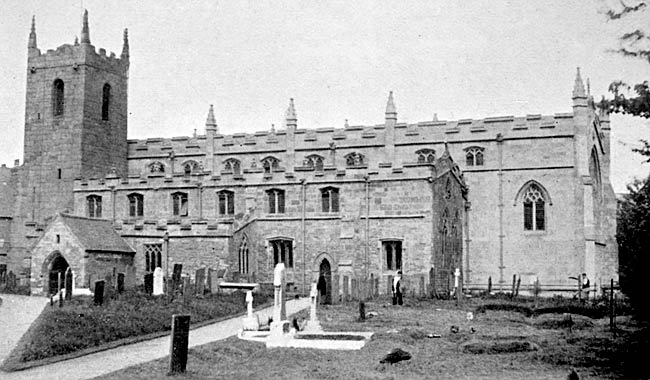

West Bridgford Church

By the Rev. C. H. B. WATSON, M.A.

West Bridgford church, c.1900.

IT is not easy for the visitor unacquainted with West Bridgford to find its parish church. As recently as sixty years ago it was the most prominent landmark of the district, and its tower could be seen, showing its pinnacles above the trees, even from the Nottingham side of the Trent, but now it is hidden by the closely packed dwelling houses with which it is almost surrounded.

The church is situated midway between Bridgford Brook, which may be seen where it emerges for a few yards from its culvert in Stratford Road, and the old Church Lane, now named Church Drive. So far as is known, the building occupies its original site.

There is no documentary proof of the dedication of the church, though throughout the centuries tradition has associated it with the name of St. Giles. Little is known about this saint, beyond the legend that he lived as a hermit somewhere in the neighbourhood of the Rhone. It is said that one day, a hind, pursued by hunters, took refuge in his cave, and that an arrow, intended for the animal, struck the hermit in the leg. Accordingly he has been chosen as the patron saint of cripples. The fact that he was also adopted by beggars and wayfarers is indicated by the large number of churches commemorating him at the gates of, or just outside, large towns.

Manor and Benefice

In the Domesday Survey of 1086 we find that though West Bridgford formed an outlying agricultural centre of the Peverel manor of Clifton,1 and had land enough for three plough teams, yet there is no mention of church or priest. In this respect West Bridgford falls short of its namesake, East Bridgford, of which we are told "There is a priest and a church and 12 acres of meadow."2 Clifton, Wilford, and even the adjacent hamlet of Adbolton, each had a church and priest, and it has been suggested that the spiritual needs of West Bridgford were ministered to by the clergy of either or both of the two latter places. Yet we know from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that a community existed in this immediate neighbourhood at any rate from the year 924, when Edward the Elder fortified the south end of the bridge over the Trent; and it is most likely that some place of worship would be provided, though it may have been extremely primitive in construction.

Under the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes this parish, belonging to the kingdom of Mercia, was probably attached successively to the dioceses of Lichfield, Lindsey, Leicester and York, though the history and extent of these ecclesiastical divisions at this period is obscure. From the middle of the tenth century, however, there is definite evidence that Nottinghamshire became an archdeaconry of York, and as such it remained until 1837, when it was transferred to Lincoln, only to become part of the new diocese of Southwell in 1884. But from the beginning of the twelfth century the Minster of St. Mary at Southwell became the pro-cathedral for the county of Nottingham. This status carried with it the interesting privilege of receiving the annual dues from the parishes, and the distribution of ‘chrism,’ which was used in the sacraments of baptism, confirmation, and extreme unction. This holy oil was consecrated at York by the archbishop, and the allowance for Nottinghamshire was sent to Southwell where it was issued on the day following Whitsunday. For the purpose of paying their “Pentecostals” or “Whitsun Farthings” and receiving their portion of “chrism,” the parishes sent representatives in procession or pilgrimage to Southwell. This practice continued down to the end of the eighteenth century, and it is noteworthy that the first account given in the churchwardens’ parish book for Bridgford, dated 1759, is for "Southwell Pentecostal Offerings,” the item being the sum of 2s. 6d.

The first rector of whom we have historical record was Luke de Crophill (or Cropwell) who was instituted 13th October, 1239.3 The patronage of the living was in the hands of the Luterells, who were lords of the manor at least from 1194 until 1418. They were probably closely connected with Nottingham, though they held the large manor of Irnham in Lincolnshire. One of the family, Galfredus Luterell, lord of Bridgford, was fined 34 shillings in 1195 for joining other gentlemen of Nottinghamshire in Earl John’s revolt against Richard I.4 In 1199 he paid 15 marks fine to regain land in the manor of Clifton of which he had been deprived as a penalty for his association with John.5 During the years 1267 to 1349 three members of the Luterell family were themselves rectors of Bridgford, one being an acolyte, a clerk in minor orders, who was instituted on the presentation of Johanna, the widow of Sir Robert Luterell, knight.

The earliest surviving documentary reference to the benefice is contained in the taxation roll of Pope Nicholas IV, which was the result of an “inquest” (1288-91) valuing all livings. All “first-fruits” (first year’s revenue) and “tenths” of benefices belonged of right to the pope, who granted the “tenths” to Edward I for six years to defray the cost of a crusade. In this survey the parish is referred to as ‘Bridgeford ad Pontem’ (Bridgford at the Bridge) and the benefice is valued at 171. 6s. 8d.

In 1341 a subsidy of “ninths” of the yield of corn, lambs and wool was granted to the king by the lords and commons of England to pay for Edward the Third’s wars in France, and the various assessments are given in the “Nonae” or “Ninths” roll. The value of the benefice of West Bridgford at this time was assessed, for taxation purposes, at 26 marks.

During the outbreaks of the Black Death which swept the midland counties in the years 1348-9, 1361-2, and 1369, and in which two-thirds of the clergy are said to have perished, it is probable that two rectors of West Bridgford were carried off by the plague. In the list of incumbents it will be seen that a new rector, John de Aslacton, was instituted in the stead of Henry Luterell 8th July, 1349; while he himself was succeeded by Thomas de Hawerthorpe, or Owthorpe, 23rd September, 1369.6

In the rolls of the mayor and sheriff’s court of the borough of Nottingham is an inventory of household goods, dated 3rd August, 1390, confiscated by order of the court from John de Halam, clerk, and Agnes his wife, for payment of debts. “Thomas, parson of the Church of Bridgeford” received nine shillings.

Considerable information relating to the patronage of the living of Bridgford is to be obtained from a post mortem inquisition dated 10th June, 1496. It was taken in Nottingham on the oath of twelve jurors, including a local man, Thomas Marshall of Brygeford, and it related to the property of Margery, widow of Godfrey Hilton, esquire. This lady was later married to a William Walron. In 1459 Godfrey and Margery had obtained by charter the manors of "Gamalston and Brygeford with the advowson of Briggeford Church” from Sir Richard Byngham, Richard Wyllughby, Robert Wyllughby, John Ingelby, Thomas Hundon, chaplain, and Thomas Byngham. By what right these men held the manor and the advowson we cannot tell, because according to the other manorial records there is an unbroken chain of succession from the Luterells to the Thymelbys through the Hiltons. It may be that they acquired the lordship from the Belesbys, into whose family an heiress of the Luterells married, and whose claim was prior to the Hiltons, to one of whom the same heiress, (Hawisia de Belesby, nee Luterell) later allied herself.7

There is a further inquest, dated 14th June, 1522, after the death of Richard Thymelby, who had married Elizabeth, the daughter of Margery Hilton, mentioned above. This Richard died lord of half the manors of Gamston and Bridgford, and the advowson of the church of Bridgford.8 The manor and advowson remained in the possession of the Thymelbys until it was sold to the Pierponts, about the end of the sixteenth century. But it would appear that Hawisia, a younger daughter of Margery Hilton and her husband Lawrence Brewerne, also held a half of the manor and advowson, since there appear in the court rolls entries of a lawsuit dated Trinity 1498 and Michaelmas 1499. A moiety was claimed from the Brewernes by Sir Henry Willughby, Thomas Hunston and Thomas Hartwell, and a recovery allowed to the same plaintiffs in 1503.9 The marked similarity in the names point to the fact that they were descendants of the owner from whom the Hiltons had obtained the lordship in 1459.

In the reign of Henry VIII a survey was made of all church revenues, known as the Valor Ecclesiasticus. This was a sequel to the dissolution of the smaller monasteries, in pursuance of an act of parliament; all "first fruits” and "tenths” were given to the king in perpetuity. In this same valuation of 1536, the annual value of the rectory of "Westburghford,” then held by Walter Basse, was given as £16 14s., while an annual pension of 2s. had to be paid to the rector of Holme (Holme Pierrepont). The place-name “Westburghford” as given in this return is interesting in connection with the “burgh” or fortress constructed on the south side of the Trent bridge by Edward the Elder or Ethelfleda, to repel the Danish attacks. It is possible that "Westburghford” had survived until the sixteenth century as a parallel to “West Bridgford” in popular speech.

Throsby’s edition of Thoroton’s history of the county (1790) gives the following information:—"Bridgford lordship is an old Inclosure; and owned principally by John Musters, Esq., of Colwick, who is Lord of the Manor . . . Thomas Fuller presented in 1692, Millicent Fuller, Widow, in 1723. Mundy Musters, Esq., in 1749. John Musters, Esq., in 1770.”10 The manor and the advowson remained in the Musters family until the land was sold for building in 1881. For over a century, from 1749 to 1862, the living was held in plurality with that of Colwick.

1 V.C.H., Notts. Vol., I, p. 269.

2. V.C.H., Notts. Vol., I, p. 2669.

3. Torre MSS.

4. Pipe Rolls, No. 40, r. 6—6 Rich. I.

5. Pipe Rolls, No. 45, r. 15, 1 John.

6. Torre MSS.

7. Inqu. Post Mortem, Notts. Vol. 1, p. 14.

8. Inqu. Post Mortem, Notts. Vol. I, p. 124.

9. Thoroton (1790 ed.), Vol. I, p. 120.

10. Thoroton I, p. 121.