St. Nicholas' church, Nottingham.

By J. HOLLAND WALKER, M.B.E., F.S.A., F.R.Hist.S.

ALTHOUGH the present church of St. Nicholas1, Nottingham, is not three hundred years old it may well represent traditions reaching back to before the Conquest, though whether it stands upon exactly the same site as its predecessor is a question yet to be debated. The first actual mention of a church of St. Nicholas in Nottingham occurs in the early days of the twelfth century, but it is possible to hazard an hypothesis which may take it back, at any rate, to the days of Edward the Confessor.

Before the Conquest, Nottingham was a small hill town defended by fortifications whose western boundaries are sufficiently marked by the present Bridlesmith Gate.2 The boundaries of Nottingham marched with those of certain manors held by private owners and no doubt these manors would conform in general with the customs usual in manors. One of these customs was that a chapel should be provided by the lord of the manor for the use of his tenants. Whatever was their subsequent development, these manorial chapels were not, in origin, parochial, and they did not necessarily enjoy the rights of font and sepulchre. They were the private property of the lord of the manor and the officiating priest was his servant who was paid by the lord in any manner which he deemed convenient. A very fine example of such a manorial chapel still exists at Deerhurst near Tewkesbury. It was founded in 1056 by Earl Odda and has come down almost intact to our day.

Two manors west of Nottingham were held during the reign of Edward the Confessor by Earl Tostig, the son of the Confessor's great minister Earl Godwin and the younger brother of Harold who was crowned king of England on Jan. 6th, 1066, after the Confessor's death.

It seems more than probable that on each of these manors was a chapel which developed into the churches of St. Peter and St. Nicholas though the details of this development are unknown. There is, indeed, no real evidence for this statement, but it seems a most reasonable hypothesis. True, there are various scattered references to "The Earl's Chapel" but the site of this mysterious building has not been satisfactorily identified. The only tangible evidence to support the existence of these manorial chapels is to be found in a stone with pre-Conquest tooling preserved in the north wall of St. Peter's church.

When William the Conqueror came to Nottingham about 1068 he found such a state of affairs that he decided that it was necessary to erect a castle here, one of whose functions was to overawe the men of Nottingham. This work he entrusted to William Peverel who chose as the site of his fortification the castle rock. Speedily there grew up around this fortress a new Nottingham which was militarised by the French followers of Peverel and their dependents, and which was called "The French Borough" to distinguish it from the older or "English Borough" on St. Mary's hill. The two boroughs were ruled by different officers under separate laws and this distinction remained until 1714. The French Borough rapidly grew in importance, and as it was the headquarters of the dominant race, it outstripped its older neighbours in culture and civilization and would need parochial arrangements. St. Nicholas' if, as seems probable, it was already in existence as a manorial chapel was obviously one of the churches to be raised to parochial rank to deal with this situation and St. Peter's the other.

But all this is mere supposition and not genuine history. The first mention of St. Nicholas' church, and it was then a parish church, occurs in the foundation deeds of Lenton Priory.3 There is a doubt as to the actual date of the foundation of Lenton Priory. Godfrey in his Parish and Priory of Lenton, argues for the foundation having occurred between 1103 and 1108, but recent investigations by Mr. H. Green would seem to throw it rather later, between 1109 and 1114.4 Whatever may have been the actual date Lenton Priory was founded by William Peverel and very handsomely endowed. Amongst other benefactions he gave to his Cluniac monks the fruits of the three Nottingham churches of St. Mary, St. Peter and St. Nicholas. St. Mary's endowments were a valuable acquisition bringing to Lenton Priory an annual income of about £27, a very substantial sum in those days, so the convent decided to take the whole of this income and to perform its parochial duties by a deputy or vicar who was paid a fixed stipend, the difference between this stipend and the total income of the living being absorbed into the income of the priory. This is why the incumbent of St. Mary's is to-day a vicar and not a rector. St. Peter's and St. Nicholas' were not so wealthy so their incumbents were both left in possession of their rectories and remain rectors until the present time. But the convent reserved an annual pension of 16/- from St. Peter's and 10/- from St. Nicholas', sums which in spite of the changes brought about by the Reformation were paid until a year or two ago to the legal descendents of the prior and convent of Lenton.

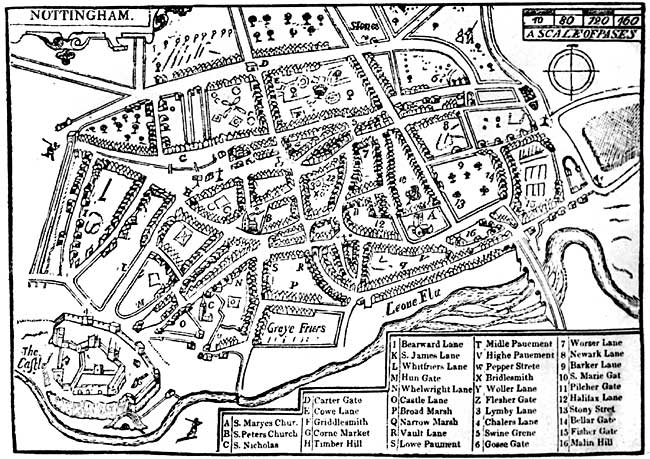

Very little can be said about this medieval church for it has completely disappeared and the details of its history are unknown. Florence of Worcester tells us that in 1177, during the fighting that took place between Reginald de Lacy, who was holding Nottingham Castle for Henry II, and Henry's rebellious sons, three ancient churches of Nottingham were destroyed. This, of course, means that whatever church was then dedicated to St. Nicholas, vanished. In Speed's plan of Nottingham, published in 1610 is a small representation of the church as it then was, which seems to be some attempt at a portrait and not a mere convention (Fig. 1). It shows the church as having possessed a western tower and spire and its general appearance must have been very like the present St. Peter's. It would be built of stone, for brick building was not general in Nottingham until Tudor times. Evidently it had aisles for on Oct. 6th, 1300, Hugh de Nottingham, the king's clerk, received license to dedicate an altar to St. Anne "in the south aisle."5 There is also a mention of a Gild of St. Mary and a Mary Mass, so there may have been a Lady Chapel.6

Fig. 1. Speed's plan of Nottingham, published 1610. C shows the only known representation of the medieval church of St. Nicholas.

Fig 2. St. Nicholas Church, Nottingham, from the south east, showing sundial destroyed by a storm in 1938 and the tracery in the belfry.

The late Mr. Harry Gill was of the opinion that the tracery in the belfry of the present tower is a relic of the ancient church (Fig. 2). It is badly weathered and difficult of access but it hardly seems so old as that. In design it closely resembles the pseudo-Gothic enrichment used after the Restoration and particularly in the fonts which replaced those destroyed by the puritans of which the font in Southwell Minster, dated 1661, is an excellent example. Preserved in the collection in Nottingham Castle is a broken stone effigy said to be a fragment of St. Nicholas' churchyard cross, but its provenance is doubtful.

For the rest, Blackner tells us that about 1800 some remains of the ancient church were discovered by the verger while digging "near the top of Rosemary Lane."7 Unfortunately, Blackner gives no particulars of what was found or the exact place where the discovery was made but his statement is important for it seems to indicate that the present church is not on the original site but a little to the south of it (Fig. 3). It will be noticed that the present church has no south door. Great importance was attached to the south door of a church in medieval times for a variety of reasons, one of which was associated with the cult of St. Christopher. St. Christopher was the guardian against accident and sudden death and a prayer to him acted as a safeguard during the day. His image was set up, where possible, on the north wall of the church opposite the south door which was usually left open so that it was in view of passers-by. On their way to work people passed by the south door of their church and almost without pausing paid their devoir to St. Christopher and so ensured their immunity from accident during the coming day. Thus it comes about that there is generally a public right of way to or past the south door of ancient churches. Rosemary Lane bounds the churchyard on the east and north, and after climbing a flight of steps terminates in a gateway in the east railing of the present churchyard. But if prolonged in imagination it will be seen to pass a few yards north of the present church and lead to a disused gateway in the western railing and so connect with St. Nicholas' Church Walk, thus cutting off a considerable area between this imaginary line and Castle Gate. It may be that Rosemary Lane represents some such ancient right of way which passed to the south of the ancient church. If this be so we may hazard the suggestion that the ancient church stood on what is now the northern part of the churchyard, between the present church and Castle Gate. The buildings, which encroach on the north east corner of this site appear to have been commenced in the seventeenth century at a time when the site was derelict. If this suggestion could be proved to be accurate it would solve several difficult problems.

Fig. 3. Plan of the neighbourhood of St. Nicholas' Church, Nottingham, showing Rosemary Lane, and the suggested site of the medieval building pulled down in 1643.

On Aug. 22nd, 1642, King Charles raised his standard upon Standard Hill and the civil war broke out. On Sept. 13th he moved off in the direction of Shrewsbury and for a short while there was an ominous pause in affairs in Nottingham. Then the half-ruinous remains of Nottingham Castle were occupied by the parliamentarians under Colonel Hutchinson and fortified as well as circumstances permitted. But although the parliamentarians were the predominating party in Nottingham, there was an influential minority of royalists who were ever on the look-out for opportunities to further the king's cause, and these royalists were ably backed by the garrison of Newark and the other cavalier strongholds in the neighbourhood. On Sept. 18th, 1643 a body of cavaliers, possibly with the connivance of Alderman Toplady, of Nottingham, obtained entrance to the town, seized St. Nicholas' Church, and used its tower as a battery from which to harass the garrison of the castle. When Colonel Hutchinson regained possession of the town he realized that he could not allow his castle guard to be exposed to this danger again and so the ancient church was pulled down and completely destroyed. What happened to the materials is unknown, they have completely disappeared, but as stone was scarce and the defences of the castle none too strong, they may have been used to reinforce these fortifications. Curiously enough the congregation of St. Nicholas' did not amalgamate with that of either St. Mary or St. Peter but remained a separate entity, and were accommodated in a gallery over the chancel of St. Peter's. But this arrangement did not last long for in the course of further fighting in January, 1644, the chancel of St. Peter's was destroyed by the parliamentarians whilst ejecting a further party of cavalier raiders.8 What happened to the unfortunate congregation of St. Nicholas' after that is unknown.

Blackner tells us that in 1714 an inscription was found in the roof of St. Nicholas' church, signed by B. Stephenson, sexton and J. Abson, rector, which read, "This church was burnt and pulled down 1647 and begun again 1671.9 1647 is manifestly incorrect for the destruction of the church was in 1643, but 1671 is probably correct for the date of the commencement of the present building, for on Sept. 8th of that year a minute occurs of the proceedings of the Town Council to the effect that ten timber trees "to be felled in the coppice" be granted for the restoration of the church. At any rate the building was complete by 1678.1

Fig. 4. Laurence Collin's house, 39, Castle Gate, built in 1664.

These dates, 1671 and 1678, are interesting for the contemplation of them throws a flood of human interest upon the church life of Nottingham at that period. 1671 is the year in which Milton published his " Paradise Lost " and 1678 is the year in which Titus Oates invented the Popish Plot. Moreover the present, or Cavendish buildings at Nottingham Castle were completed in 1679. Readers of Pepys's Diary, John Evelyn's Journal and other Restoration memoirs will realize that church life was at a low ebb during the reign of Charles II, and that apart from Wren's work rendered necessary by the fire of London very little ecclesiastical building was undertaken. And yet during this dismal period the faithful remnant of St. Nicholas' congregation set about the complete rebuilding of their church and brought their task to a successful conclusion. It may be wondered whether this remarkable achievement was due to the leadership of Laurence Collin, the founder of the family whose charity was to do so much for Nottingham. His house with its date stone 1664 (Fig. 4) still stands but a stone's-throw away from the church.12 At any rate, the building reflects contemporary conditions, for the materia] used is of the most economical description and there is a marked absence of ornament. Finances appear to have been difficult, for the living was vacant from 1672 to 1681 when John Simpson became rector. Typical seventeenth century bricks are noticeable in the tower where, although there is much random building, a good deal of English bond is observable.

1. St. Nicholas, the saint to whom the church is dedicated, was one of the most popular of patrons. His cult reached England in the tenth or early eleventh century, and by the Reformation no less than 376 churches were dedicated in his name. His career offers no satisfactory explanation of this popularity. He was a much-loved bishop of Myra in Asia Minor, who narrowly escaped martyrdom under Diocletian and died eventually from natural causes in 326 A.D. His relics were soon discovered to possess miraculous powers and almost fantastic legends developed out of his rather prosaic life-story. He became, in particular, the favourite patron of children, of sailors, and of bankers and merchants. For fuller details see the Encyclopedia Britannica, Chambers' Biographical Dictionary, and Jameson, Sacred and Legendary Art, (1857).

3. For the topography of ancient Nottingham see paper by W. H. Stevenson in the Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 1918.

4. Godfrey, Parish and Priory of Lenton, p. 64.

5. Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 1936, p. 83.

6. Stapleton, Religious Institutions of Nottingham, vol. IV, p. 57.

7. Ibid.

8. Blackner, History of Nottingham, p. 97.

9. Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 1938, p. 33.

10. Blackner, History of Nottingham, p. 97.

11. Ibid.

12 Number 41, Castle Gate.