Church St. Mary and St. Martin, Blyth

By J. HOLLAND WALKER, M.B.E., F.S.A., F.R.HIST.S.

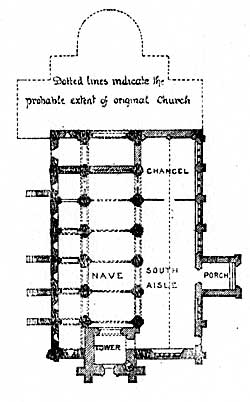

Plan of the Church of St Mary and St Martin, Blyth.

ROGER DE BUSLI was a faithful follower of the Conqueror, and after the overthrow of the English host near Hastings, William rewarded him with such grants of lands that his possessions, which were centred upon his castle at Tickhill, were so great that they formed one of the most important honours in the Midlands.

Amongst his estates was the town of Blyth, or Blyth-ford as it may then have been called, commemorating the ford over the River Blyth, which is nowadays called the Ryton, and here in 1088 Roger de Busli established a Benedictine Priory subject to the great Abbey of St. Katharine at Rouen, and therefore open to French rather than to English influences. In spite of its position upon the North Road, this Priory never obtained to great eminence, and at its dissolution in 1535 its income only amounted to £125. It is well to note, however, that the rectory of Blyth was impropriated to its use, so that the prior and convent became rectors and the parochial duties were carried out by their vicar.

The domestic buildings of the Priory have almost completely disappeared, and what little is left is not of much general interest, but a great part of the church remains and its architecture is of the greatest importance.

The dedication is to St. Mary and St. Martin, and the church originally consisted of a nave of seven bays with north and south aisles, a transept with a central tower and an apsed eastern wing. All except the nave and the north aisle have disappeared.

Church of St Mary and St Martin, Blyth. Panels on screen in present nave: St. Helena, St. Barbara, St. Ursula.

The Norman work of the nave and aisle is amongst the earliest in the country, and it dates from 1088. Of contemporary work, Ely was begun in 1083, Malvern in 1084 and Gloucester in 1090, but the plan of the piers in each of these cases is circular, while at Blyth we have a rectangular plan with attached half-columns. This variation from the normal probably represents French influence exercised by the mother-house at Rouen.

The masonry is crudely and widely jointed, and the stones bear frequent marks of the axe, for the chisel did not come into general use until about the year 1100. But in judging the original appearance of the church, it should be remembered that colour, of which there remain considerable traces here and there throughout the church, was freely used.

The piers stand upon bases with characteristic convex moulding, and the capitals are extremely interesting, for the knops at the corners represent the last remnant of the classical Corinthian capital. These knops are the final debasement of the corniculae, and if they were cut away, the typical Norman cushion-capital would reveal itself. The arches are recessed in two orders and rest, rather awkwardly, upon square abaci which have nothing whatever to do with the arch-orders.

On the south side, the triforium arches are untouched, but on the north debased tracery has been inserted at some time after the Reformation. The triforium passages with their lean-to roofs have disappeared. As the triforium arches are of the same diameter as those of the nave arcade, the effect produced is curiously reminiscent of Southwell Minster which was not commenced until about 1110, and the question as to whether Blyth set the problem of tracery for this type of triforium, which the Southwell masons found themselves unable to solve, arises.

The interest of the clerestory is that the plainness of the two lower arcades has been abandoned, and nook-shafts have been introduced showing a change of fashion during the progress of the work.

Church of St Mary and St Martin, Blyth. Panels on screen in present nave: St. Stephen, St. Euphemia, St. Edmund.

The north aisle remains in its original condition, and is ceiled by a series of groins. Groins are not true vaults and are exceedingly difficult to build. Rib-vaulting did not come into use until the Transitional period, and groins were the best contribution that early builders could make to a fireproof building. As the compartments of this aisle are oblong on plan and not square, the builders encountered great difficulties, which are reflected in the distortion of the cross-arches. In the western wall of this aisle are patches of brick building for which it is difficult to account. The usual explanation that this is re-used Roman material from Danum or elsewhere seems rather unsatisfactory.

Evidently the builders meant to put up some sort of stone vault over the nave, for they provided vaulting-shafts. But their courage seems to have failed them, and it may be that a high-pitched timber roof was provided, closed by a flat ceiling, possibly painted like the one at Peterborough.

Church of St Mary and St Martin, Blyth. Interior of North Aisle, showing Groining, 1088, and distortion of Cross Arches.

About 1180 the Norman south aisle was pulled down and a new aisle in the Early English style was erected. Of this nothing remains, but the two graceful arches by which it communicated with the south transept form, in their blocked-up condition, a beautiful reredos for the present high altar. To this period also belongs the south porch and the charming quadripartite vault with its display of bosses over the nave.

This work seems to mark the incorporation of the parish church of Blyth into the monastic church. There is a tradition that the original parish church stood on a mound at the south of the village, where the school now stands, and it would seem that after its destruction the present schoolhouse, with its delightful 13th-century door with dog-tooth ornament, was erected for some ecclesiastical purpose that is now obscure. The probable explanation of this tightening of the ties between the Priory and the parish was that Coeur de Lion was engaged in his wars with Philip Augustus, and the monks saw a possible danger in their close association with St. Katharine’s Abbey in Rouen, and desired to strengthen their English connections. At any rate, it is interesting to remember that this Early English work was erected during the lifetime of St. Francis of Assisi.