Norwell

Norwell Church.

By THOS. M. BLAGG, F.S.A

THE bulk of the land in the parish of Norwell has belonged to the church perhaps from the time of King Edgar the Saxon (959-75), who is said to have given it to the church of St. Mary at Southwell nearly one thousand years ago, and possibly from the days of St. Eadburgh nearly three hundred years before that.

There is recorded to have been a royal grant about 956 from King Edwy to Oskitel, the Danish Archbishop of York, of 20 “mansas” at Southwell, and this is possibly the origin of that part of the Liberty lying "within the manor" of Southwell; while Aldred, Archbishop of York 1061-1069 is said to have purchased lands at his own cost and with them formed Prebends at Southwell. It seems likely that Aldred’s endowments may be represented by the Norwell estate, but the destruction of muniments at Southwell (of which we have a description) at the time of the Great Rebellion, irrevocably lost us any early charters not recorded in the Liber Albus, and Saxon charters were possibly beyond the ability of the compilers to transcribe.

The church lands here were divided into three prebends named Overhall, Palacehall or Netherhall, and Norwell Tertia Pars. Of these Overhall was the richest.

Besides the ecclesiastical manors mentioned, there were manors in the hamlets of Norwell Woodhouse, Middlethorpe and Willoughby, also within the parish.

Carlton-on-Trent, or North Carlton, was also a chapelry of Norwell. All these manors had moated manor houses, and five or six of these moated sites of the homestead type may be traced to-day, of which you can see a good specimen almost adjoining the churchyard in the grass field on the south side. The moat is intact, though silted up at the bottom, and the enclosure is fenced round and used as a kitchen garden. This I take it was the site of Overhall, the principal prebendal manor.

With regard to Palacehall, so long the home of the Sturtevant family, a great portion of the house still stands and is inhabited, though divided up into tenements.

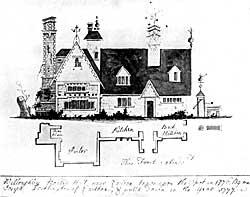

Old hall at Willoughby, near Norwell.

At Willoughby, which lies between Norwell and Carlton-on-Trent, there were two principal houses, and Throsby, writing about 1795 (Vol. III., p. 167) says of them, "The houses that formerly stood here are decayed and gone. The ancient manor house, which was large, with an adjoining chapel, was a ruin in 1785, when the very foundations were dug up, and the materials disposed of by Mr. Bristow. In the ruined chapel was found a font decayed, and under a floorstone the skeleton of a child." That house possibly occupied the site of the 14th century manor house of John de Lisours, and may now be indicated by some traces in a field which Mrs. Vere-Laurie informs me is still known as "Castle-field," but which I have not had an opportunity to examine. The other house stood near the present railway line, where its moated site, in a small plantation now occupied by a rookery, may still be seen.

It was pulled down in 1777 by the owner, Joseph Pocklington, who fortunately made a drawing before demolition which is in the possession of Mrs. VereLaurie, who has very kindly allowed me to use it as an illustration for this paper. This drawing was reproduced as a woodcut by Pocklington’s friend, William Dickinson, in his History of Newark, where it will usually be found at p. 69 of the 1819 edition. But it there appears "without rhyme or reason," being nowhere described or alluded to in the text. It is interesting to compare this woodcut with the original drawing, and to observe how the draughtsman has omitted and altered details in transferring it to his block.

At one of these Willoughby houses Agnes Hatfield, mother of Archbishop Cranmer, was probably born and lived; for her grandfather Lawrence Hatfield had bought it in 1456, and as he is later described as "of Willoughby," he presumably lived there. According to the Inquisition Post Mortem of his grandson, Henry Hatfield of Willoughby, in 1541 (printed in our Society’s Record Series, Vol. III., p. 266), this house was then known as “Bekerdes Hall” in Willoughby, and in Henry Hatfield’s marriage settlement in 1528 he had made Thomas “Cranmore,” Doctor of Theology, and presumably his nephew, one of his trustees. This house, “ Bekerdes Hall,” seems to have been the Lisour’s manor, for Thoroton appears to record from early Deeds and Fines the conveyance of the Hatfields’ property here from the Malets to the Lisours and, after some generations, to William Foljambe in 1443, from whom through trustees or mortgagees, it was conveyed to Lawrence Hatfield in 1456.

As an ecclesiastical estate Norwell enjoyed a benevolent and settled government throughout the medieval period, and was a populous and prosperous village community with a weekly market every Thursday and a fair of three days’ duration every year, on the Eve, Feast and Morrow of Holy Trinity. The prebendal manors were mostly leased for lives or succession of lives to various lay families, some of whom, like the Lees at Overhall and the Sturtevants at Palacehall, were of gentle rank and prominent in the parish for several generations in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The customs of the prebendal manors were not harsh, but betokened a happy relationship betwixt lord and tenants, for a document! of the early years of the 15th century when setting out the boon days and services of bond tenants, as well as free natives, and their sustenance, tells us for instance that after mowing the lord’s meadow the twenty-four mowers “shall eat in the prebendal house as follows :—first, they shall have bread and beer, potage, beef, pork and lamb for the first course; and for the second, broth, pigs, ducks, veal or lamb roasted; and, after dinner they are to sit and drink, and then go in and out of the hall three times, drinking each time they return, which being done, they shall have a bucket of beer, containing eight flagons and a half, which bucket ought to be carried on the shoulders of two men through the midst of the town from the prebendal house unto the aforesaid meadow, where they are to divert themselves with plays the remainder of the day, at which plays the lord shall give two pairs of white gloves,”—all this for mowing about half an acre apiece, for the size of the meadow was only thirteen acres. Feudal England was indeed Merrie England and “a land fit for heroes to live in,” in a sense that industrialised and urbanised England can never become.

.