< Previous | Contents | Next >

Standard Hill and Postern Street

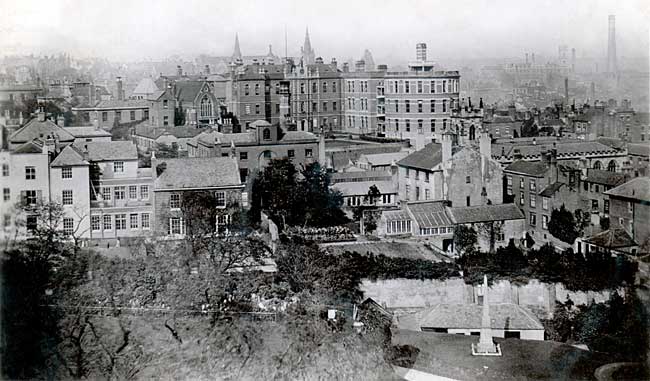

View of Standard Hill from Nottingham Castle, c.1910.

Standard Hill and Postern Street may be taken as being part of one and the same thoroughfare and represent an ancient trackway through the park and so out westward. This trackway was pushed northward to Park Steps when the castle enclosure was made as we have already seen. So long ago as 1446 this neighbourhood is mentioned under the name of the Castle Hills, but Standard Hill itself appears to have been called The Hollows as late as 1844. It was a more or less derelict neighbourhood and there were no houses between Park Street and St. James's Street until 1750. The district to the east where Rutland Street and its tributaries now stand was spoken of as Rutland Gardens and remained in the hands of the Rutland family as descendants of the John Manners who acquired property of the Carmelite Friars about 1573.

In 1808, 9,000 square yards of land, being part of the castle estate, was sold by the Duke of Newcastle for 15/- per yard. He imposed certain conditions amongst which was the fact that no houses were to be erected upon it of a less annual value than £25 and that no factory was to be erected in the neighbourhood. This land being part of the Castle estate was, like Brew House Yard, extra parochial, and so remained until about 1910. This is a point which is well worth remembering when we come to consider the events leading to the construction of St. James's Church.

Plaque commemorating the raising of King Charles's standard in 1642.

It was on this land at a point marked by a stone in the roadway at the corner of King Charles Street and Standard Hill just by the west door of St. James's Church that King Charles I. is traditionally said to have raised his standard on August 22nd, 1642, at the commencement of the terrible Civil War between the King and the Parliament. Of the events which led up to this occasion this is hardly the place to speak, but the standard appears to have been originally set up upon the summit of Richard III.'s Castle of Care whose foundations as we have seen still remain in Castle Grove, but as the standard attracted few recruits it was decided to move it outside the castle area for it was thought that recruits were deterred from coming forward by the fact that the standard stood within the castle area and so it was set up on this rocky knoll which in those days was called Hill Close which name was changed to Standard Close in memory of the occasion.

St James' church, Standard Hill, c.1815.

St. James's Church is not a particularly beautiful structure, but the history of the events leading to its erection is not without interest. About 1805 it was felt that the ministrations of the three parish churches of Nottingham, St. Mary's, St. Peter's and St. Nicholas's, did not meet the spiritual requirements of the day and so an effort was made to establish a fourth church, the religious views of whose incumbent should be more in keeping with those accepted by the promoters of this scheme. But great difficulties were encountered, for the three parish clergy were very much averse to the introduction of another clergyman of whose views they might disapprove and which might possibly affect them very materially by taking from them altar dues, and so they strongly opposed the erection of a church in any of their three parishes and the scheme had to be abandoned.

However, it was revived two years later, and in 1807 an Act of Parliament was obtained which sanctioned the erection of a new church, and land was acquired in the extra-parochial district of Standard Hill over which none of the clergy in question could have any jurisdiction. Although they were unable to prevent the establishment of this church the three clergymen succeeded in clogging its usefulness by imposing a good many conditions upon it. For example it had no parish whatever, a disadvantage under which it laboured until quite recent times and, further than this, marriages could not be celebrated in it during the first years of its existence. However, the scheme was proceeded with and in 1808 a corner stone was laid. The Rev. J. H. Maddock acted as Chaplain and a brass plate was laid in a cavity under the corner stone bearing the names of Thomas Hill, Edmund Wright, Richard Eaton and Benjamin Maddock, the principal movers in the scheme. The building proceeded and in 1809 the edifice was consecrated and dedicated to St. James by the Archbishop of York. The dedication was probably chosen to preserve the memory of the mysterious chapel of St. James which existed in pre-Conquest days somewhere in this neighbourhood, but one curious fact arose out of the extraordinary conditions of the founding of this church was that the ground floor pews were freehold and carried with them a vote in elections. This rendered them exceedingly valuable and led to all sorts of difficulties in modern times.

The exterior architecture of the church is contemptible although the design is from no less a person than Mr. Stretton. It speaks, I think, of the lowest depth to which the church architecture sunk. The bell which hangs in the tower was cast in 1791 by Hedderley for a cotton mill in Broad Marsh. But although the exterior is so deplorable the interior is substantial, comfortable and striking, and really if considered properly is rather impressive. It has huge galleries and the treatment of the front of these galleries in different woods produces a very striking effect. It is perhaps a little unfortunate that the homogenity of the style is marred by the Gothic screen and organ case and pulpit, for although each of these are good modern work they rather clash with the rest of the building. The position of the pulpit, by the way, has always been a great difficulty for the church authorities and it seems almost impossible so to place it that the preacher may be seen from the galleries and yet to prevent it blocking the view of the east end. There is nothing of particular interest in the furniture of the church except perhaps the Royal Coat of Arms, which is affixed to the front of the western gallery. The church has a particularly interesting musical history and it is well to remember that the first organ was not placed in the church until 1815, six years after the church had been consecrated.

The General Hospital is now home to Nottingham City

Primary Care Trust (A Nicholson, 2004).

The General Hospital is now home to Nottingham City

Primary Care Trust (A Nicholson, 2004).The General Hospital which is the most successfully managed voluntary hospital in the whole of England takes its origin from the last quarter of the 18th century. The foundation stone was laid on February 12th, 1781, by John Smelley who was then Mayor of Nottingham and it is rather amusing to remember that in his address to the crowd upon that occasion he found it necessary to implore them to mark their approval of the good work which was to be done in the hospital by preserving order and not rioting upon the occasion of the stone laying. Half the ground upon which the hospital was to be erected was provided by the Duke of Newcastle and the other half by the Corporation of Nottingham which is probably why the Mayor figured so highly on the occasion. An elaborate procession was formed at the Shire Hall consisting of all the noteworthies of the district, this proceeded to the Town Hall where it was joined by the Civic Authorities, and so wended its way to the site of the function. The architect of the original building was John Simpson and Blackner preserved an extremely interesting list of benefactors and donors to the original cost of the building. The hospital was opened to receive patients on September 28th, 1782, and the occasion was one of much rejoicing. The day was ushered in by the ringing of bells, and in the forenoon a service was held in St. Mary's Church and in the evening a great public dinner was given in Thurland Hall, after which a concert and ball was held at the Assembly Room.

The ninth patient to be treated in the hospital was Kitty Hudson and her case was surely one of the most extraordinary ones which has ever been treated in the institution. As a child she was wont to assist in the cleaning of St. Mary's Church and she contracted the strange habit of picking up pins and needles and chewing them. To such an extent had she carried this extraordinary practice that she wore her teeth away and swallowed innumerable pins and needles. For many years she felt no ill effects, but gradually she began to complain of numbness here and there in her body and pins and needles began to work out of various parts of her person. Her condition gradually became worse and worse and for a long time she was detained in the hospital undergoing countless operations and passing through great agonies in getting rid of these strange articles. Eventually she was cured and became the post woman carrying the mail between Nottingham and Arnold and lived to be the happy mother of a healthy family.

This is not the place to tell of the wonderful history of the Nottingham General Hospital or speak of the marvellous work of its doctors, but it is very pleasant to think that this modern hospital with all its marvellous character and skill and devotion to afflicted humanity should stand so close to the Bog Holes, the ancient hospitals of Nottingham, where plague stricken patients were left to die or get well as best they could under the tender mercies of the Town Pavior.