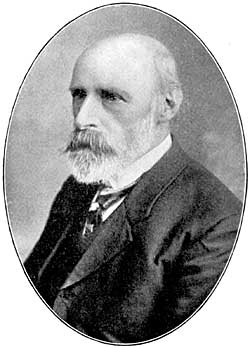

William Stevenson.

By Thos. M. Blagg, F.S.A.

WILLIAM STEVENSON.

ON the 27th of January, 1922, in his ninetieth year, William Stevenson passed away at Westgate House, Halstead, in Essex, and three days later was buried in Halstead Cemetery.

Early on the morning of the 27th July, 1897, the late Cornelius Brown and the writer were seated in the coffee-room of the "Chesterfield Arms" at Bingham, awaiting the assembling of members for the first Excursion of the Thoroton Society, when the sound of approaching talk caused Brown to exclaim "Stevenson's voice for a million!"—and a moment later I was being introduced to one whose name and work were already familiar to me and who was thenceforth to become a friend of the first degree of regard.

Just six feet in height, though thin and with a slight stoop, bald, with a domed skull rather narrow, but of exceptional length—the most typically dolichocephalic skull I ever saw on living shoulders—small, bright, scintillating blue eyes, deeply set; a grizzled beard, somewhat pointed; a sweeping grey moustache to which he occasionally gave a forward-turning twist, William Stevenson was a man of fine presence and striking appearance. His voice was deep, resonant and flexible, and when reading any of his papers before this and other Societies, he had a habit of dropping it a tone or two in the peroration, or the close of a descriptive sentence, which his rich imagination and poetic ear had framed of choice words of the exactest nicety with which to paint some imagery of mediaeval pageant, some glory of architectural beauty, or some achievement of a famous man of old.

William Stevenson was born at Grantham, 8th December, 1832, the son of Michael Stevenson and Charlotte (Jarvis) his wife, and the grandson of John Stevenson of Louth, who himself lived to the great age of ninety-one. Michael Stevenson altered the spelling of his name from Stephenson about the time that he went to Grantham. He was a master-carpenter and cabinet maker by trade, and while his children were still quite young, moved from Grantham to Nottingham. There his younger son William was apprenticed to him on reaching the customary age of fourteen years, after having left school when nine years old, and working as a boy in Reader's lace-machine engineering works. Michael the father died early in 1851, of cholera, and William Stevenson took charge of the business. During the short association of father and son, they had among other work undertaken the re-seating of Bingham Church, and sixty years later William Stevenson when visiting that church with the writer, sought to pick out one of the "poppy-head" bench-ends which he remembered having carved with his own hands as an apprentice.

Staircase-building was a speciality with the Stevensons at Nottingham, and the son always took pride in his ability to "set out" and work the difficult rising curves of hand-rail and balustrade, which the craftsman had to translate from the artist's flat drawing to the dimensions and idiosyncracies of the living wood. He made the wooden spiral staircase in Bromley House Library, Nottingham.

After conducting the family business for some time, Mr. Stevenson decided to become a wholesale timber merchant and importer; and to get an insight into the commercial practice of the trade (his practical knowledge was already pre-eminent) took an engagement with the late Mr. Wm Hammersley of Nottingham, one of the largest merchants in the Midlands. This engagement lasted one year and was the only period during his long life, as he found satisfaction in telling, when Stevenson was not his own master.

After a few years as a timber merchant in Nottingham, he settled in Hull in 1869, and save for a six years' residence in Scarborough, remained there till the end of 1906, first as senior partner of the firm of Stevenson, Hudston & Ford, established at North Side, Queen's Dock, and from 1896 as partner with Mr. Henry Toogood in the Hull Timber & Sawmills Co. Mr. Stevenson specialised in hardwoods and was one of the best judges of oak and mahogany logs in the kingdom. At various times he visited Norway, Sweden, Russia, Belgium and Germany to observe the forests and trade conditions; while his knowledge and judgement caused him to be in considerable request all over England as a surveyor and arbitrator in cases of timber fires, salvage disputes, etc.

On 14th August, 1855, Stevenson married Mary Ann, daughter of John and Rosina Lennon of Banbridge, Ireland. She died at Hull, 10th October, 1890, leaving two sons, William Henry and Charles Lennon, and one daughter, Mrs. Lawson. A younger daughter, Mrs. Merrill, died in Sheffield eight months before her mother. The brilliant career of the eldest son was always a source of pride and satisfaction to his father. He was elected to a Research Fellowship at Exeter College, Oxford, in 1895, and created M.A. by Decree. He edited the four stout volumes of the Borough Records of Nottingham, the Crawford Charters in the Bodleian and the Close Rolls of Edward I., II. and III. in the P.R.O., and is also known by his critical edition of Asser's Life of Alfred.

At Christmas 1906, William Stevenson left Hull, retiring from active business, and with his devoted younger son Charles, went to live with his daughter, Mrs. Lawson, at Alfreton, dedicating the remainder of his years to his archaeological studies and to literary work, both antiquarian and technical. In March, 1921, the household removed to Halstead in Essex, whence letters written at eighty-nine years of age and within a few weeks of his unexpected death (he was carried off by pneumonia) shew him just as industrious, just as shrewd and alert mentally, just as full of interest in his surroundings and in passing events, just as zestful of life, as in any other of the twenty-five years of our friendship.

In connection with his trade, Stevenson wrote two books—"Trees of Commerce," (Rider's Technical Series), which has gone through two editions, and "Wood; its use as a constructive Material" (B. T. Batsford, 1895). To Papers such as the "Timber Trades Journal," the "Illustrated Carpenter and Builder," the Estate Clerk of the Works "Journal" and the "Building News," he contributed an enormous number of articles and letters replete with original information. In the domain of Archaeology he has left one book, "Bygone Nottinghamshire," 1893, entirely written by himself, and hundreds of articles contributed to the press and to various journals, sometimes singly, sometimes in series, such as "The Religious Institutions of Old Nottingham" 1894-1899, written in collaboration with Mr. Alfred Stapleton and reprinted in three vols.; "The Domesday Survey of Nottingham" contributed to the "Nottingham Guardian " in 1914, and so on.

Of the Thoroton Society he was one of the original Members and was elected a vice-president in 1904. His numerous contributions to the Society's " Transactions" bear witness to his active interest in its work.

The striking characteristic of Stevenson's work was its constructive nature,—his powers of observation enabled him to lay hold of features hitherto un-noted, and his accumulation of knowledge enabled him to build from them theories which, if occasionally unsubstantiated, in the majority of instances were carried to convincing conclusion. To great technical knowledge of wood and stone and other materials and of tools and methods of workmanship, he brought powers of observation, both natural and trained, of almost uncanny acuteness, and an ability to focus a wide range of general knowledge on the object with which he was dealing. "Stories in Stone" were as vivid to him as stories in words: and when confronted with earthwork or ruin, house or church, or castle never seen before, the small keen blue eyes passed to the brain an assemblage of the facts they looked on, which his mind fitted together in due sequence and illuminated with parallel and simile, enabling him to pass to his audience a constructive and logical history. A map became to him a landscape and a landscape a history, to which his knowledge of geology, botany, agriculture, architecture and archaeology provided each its key.

To all this equipment was added an imagination which amounted to insight and a diligence which never tired. Every week of his long life was of interest to him yielding its due harvest. Daily he garnered the grain of knowledge and winnowed the wheat from the chaff. For nearly ninety years he "saw nought common on God's earth" and truly, in the words of Eliphaz the Temanite, he "came to his grave in a full age, like as a shock ol corn cometh in in his season."