The Church of St. Mary, Orston.

By Mr. Harry Gill.

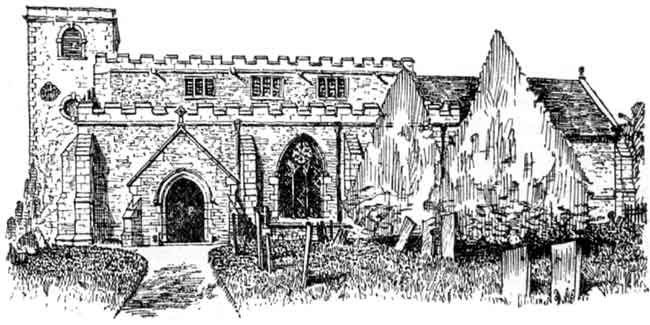

Orston church in 1907.

Orston church in 1907.AT first sight this church does not arrest the attention of the antiquary owing to the modernized exterior, but when well seen into it is found to be full of interest. The south porch is obviously and entirely new (1888) and the remainder of the south front has been renewed in parts again and again.

The necessity for these frequent reparations is attributable to the geological formation of the site. The whole of the Vale of Belvoir was at one time a lake, the clay bed whereof shrinks and swells with every change of temperature, and thus plays havoc with foundations; witness the billowy effect seen in the floor of this church—which is in one level throughout its entire length; and in the wavy lines of a horizontal scroll-moulding which runs beneath the window-sills in the north aisle.

The antiquity of the building is apparent on entering. The spreading arches of the pier-arcades, the beauty and variety of the window tracery, and the sense of size and spaciousness,1 all proclaim that when in its pristine condition this church was important and beautiful.

No written records of the earlier building epochs are extant, but history may be read from the stones. The pier-arcades are the most ancient part of the work now visible, albeit they have been altered from their original condition in order to conform with the later additions.

To all who are familiar with mediaeval architecture the alternating cylindrical and octagonal piers standing upon "water-holding" base mouldings and capped with right-angle head mouldings, the semi-circular arches in two recessed orders, having plain double chamfers to the south arcade and keeled bowtells to the north arcade, speak of the "Transition" period between the Norman and the Early English style of architecture—and are thus eloquent of the closing years of the I2th century (Henry II.).

The Society paid a visit to another church, almost identical with this so far as the pier-arcades are concerned, at Edwinstowe. Although some distance apart there is reason why the churches of St. Mary at Orston and St. Mary at Edwinstowe are so much akin.

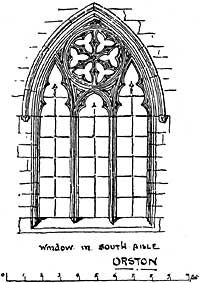

Window in south aisle, Orston.

In Domesday, the manor of Orston and the manor of Mansfield (whereof Edwinstowe

was a berewick) were both held of the King. In 1093, King William Rufus gave

both these churches with their emoluments to the Bishop of Lincoln. It is

therefore a fair assumption that not very long after the date of the gift

the famous masons from the Guild of St. Mary at Lincoln would be set to

work to replace the pre-conquest buildings with more imposing structures,

the remains whereof are before us to-day. The stonework of the interior

still retains its original character, although it has been dressed over

and in parts renewed again and again.

In spite of these reparations mason-marks and incised inscriptions in "black

letter" may be found on the piers but these doubtless date from the

14th century reconstruction, to be mentioned in detail later.

The chancel is a little later and wider than the nave. It dates from the

middle of the 13th century (Henry III.). The plan conforms with the idea

then prevailing, of a double square. The windows—three single lancets

on either side and a triple lancet at the east end—are elegant examples

of their kind, graceful in shape and pleasing in their proportions. Their

hood mouldings have, for the most part, characteristic "mask" terminals,

but here and there a fully developed carved head appears to have emerged

from the embryonic state. A beautiful two-light window, to the west of the

priest's door, was made for the accommodation of an acolyte, whose duty it

was to ring the sacring bell at a shuttered opening which took the place

of the lower panes of the window.

There is evidence that the original aisles were much narrower than we see them now, so that, if we wish to trace the development of the church in chronological sequence, the enlargement of the south aisle to its present width (18ft.) must first be considered. This extension was necessary in order to obtain a side chapel. A piscina in the south wall, with stone credence, still remains to indicate the position of the altar.

I think the inception of this chapel was due to a benefactress whose effigy we shall shortly have occasion to notice.

It is clear from the style of it that this chapel was built toward the end of the reign of Edward I., or early in the reign of Edward II. The tracery of the windows, especially the one eastward of the south porch, is exotic. Nothing like it had been seen in this neighbourhood before. I made a drawing of it in 1874, ere yet the hand of the "restorer" had been laid upon it, which shews that the design of it is still unaltered, and I know that some of the ancient stonework is retained in its composition.

The end windows of this aisle are 15th century, substitutions, but the obvious discrepancy between the jamb mouldings and the tracery heads suggest that when in their original condition these windows would resemble the others.

I venture a suggestion that the wonderful work in the newly founded college chapel at Merton (1274-1308) most probably inspired someone to emulation in this south aisle. We cannot determine who it was, but we may cherish supposition. Was Anselmus de Stokyng, the second vicar here of whom we have any record (1292-1321) an alumnus of Merton? Was he impressed, not so much by the theology at Merton as by the architecture of his college chapel, and thus led to direct a reproduction in miniature here? or did the master-mason of the Lincoln Guild of Craftsmen hail from Merton? Not at all unlikely, for, apart from the priesthood, there was no vocation in that day more attractive to a learned man of peace than architecture.

The north aisle was brought to equal width with the south aisle at a somewhat later date. By comparison, the windows are large in scale and clumsy in design. These facts point to a late 14th century date, say the closing years of the reign of Edward III. The plague-stricken year would thus intervene between the erection of the south aisle and the north aisle. This suggestion gains support from the processional doorway on the north side, (now blocked) a feature which came into general use at the time of the "Black Death" (1349).

A fine stone effigy now lies on the floor at the east end of the north aisle, whence it was removed from the sill of the north-west window, and before that it lay in the chancel.

My enquiries have led me to think that the effigy was not originally set up in this church at all, but that it was brought here from the monastic church of St. Mary at Newstead (Stamford) at the time of the suppression, just as other early effigies of the great families of de Roos and Manners were removed from the Priory Church of Belvoir and the Abbey Church of Croxton to Bottesford church.

|

The effigy carries no inscription, but the style of dress, the diminutive angels which smooth the pillow, and the details of the canopy proclaim it to be workmanship of the early 14th century. Traces of lineage however, are borne on two small shields: one, above the right shoulder, bears three water bougets for de Roos, Lords of Belvoir, and of the manor of Orston in the late 13th and 14th century.

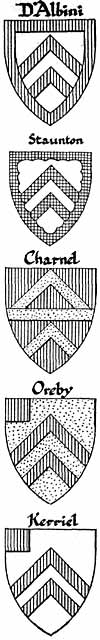

These arms were originally borne by the great family of Trusbut of Wartre in Holderness, hence "Trois boutz d'eau" was indicative of their name and estates. When the sole heiress of Trusbut was married to a de Roos, he took to himself their arms—gules three water bougets or. The shield above the left shoulder bears two chevrons within a bordure which I read to be D'Albini, the predecessors of de Roos, in the Lordship of Belvoir in the 12th and 13th centuries—argent two chevrons within a bordure gules.

The followers of D'Albini, who lived on adjacent manors, and who were called upon to attend their lord in times of need, were distinguished by coat armour only slightly differenced from their superior lord. For instance, the Stauntons of Staunton, who held their lands by "tenure of castle guard," bore the same ordinaries sable with the bordure engrailed. They lived within sight of the castle of Belvoir, and were under obligation to repair thither with their retainers whenever the standard flew from the summit of the Keep.

The Charnels of Muston bore gules a fesse or between two chevrons or.

The Orebys of Abb Kettleby—or two chevrons and a canton gules.

The Kerriels of Croxton argent two chevrons and a canton gules.

Authorities differ slightly in the rendering of these arms, but I have followed our own historian Dr. Thoroton.

(1) Nave and Aisles together measure 55ft. in width.