The Church of St. Mary, Clifton

A STUDY IN MEDIAEVAL MASON-CRAFT. No. 2.1

By MR. HARRY GILL.

The Church of St. Mary, Clifton (photo: A Nicholson, 2005).

BEAUTIFUL for situation, the ancient settlement on the cliff, known as Clifton (Cliff-ton) has given a name to one of the most famous families of the Middle Ages.

Its position, in a sheltered comb near the top of the wooded cliff overlooking the Trent about four miles above Nottingham, appealed to the Anglo Saxons, no doubt, on account of its immunity from a surprise attack by marauding Danes, who used the splendid waterway which flows right across the county from south to north for purposes of aggression. By means of the river they had reached as far as Nottingham in A.D. 865, and three years later they over-ran the county.

In after years this same river became a highway for commerce, and when in due course the little Saxon church came to be enlarged again and yet again, to meet the ever growing needs, its nearness to the river bank gave to successive generations of builders a wide choice of building material to draw from.

At the first glance it is apparent, that, not counting modern renovations, three main building epochs are indicated by the different geological characters of the materials used.

First we have the original walls and the very early enlargements carried out in thin-coursed rubble walling, smeared over the surface both within and without with mortar. This may still be seen at the west end, and part of the south side. The stone used for the rubble walling was obtained on the site; the worked stone in dressings and angle quoins, locally known as "skerry" or "water-stone," was obtained from a deeper level of the marl in close proximity to the site.

Next in point of time is the ashlar masonry of the clerestory and the tower, executed in coal-measures sandstone from quarries on the Derbyshire border, which came into use during the reign of Richard II. The stone is in large blocks, warm yellow in tint, stained with streaks and blotches of iron. The Erewash and the Trent would provide ample means of transport from the quarries to the site.

In the 15th century a very hard crystalline millstone grit was quarried in South Derbyshire and district. An extensive bed of this stone was found at Castle Donington, and again the river would form the means of transport all the way from the quarry to the site, where the stone is used in the chancel and the north transept.

When we begin to analyse the architecture, we find that the restoration of the church under Sir Juckes Clifton in 1852, and the repairs and additions of later years, have removed some of the marks of identification, and made it difficult to read with assurance from the stones alone. Nevertheless, with a little aid from the monumental inscriptions, and from contemporary MSS. the history may be pieced together with a fair degree of accuracy.

If we turn to the pages of Domesday Book we may learn that even at that distant date (1086) there was "a church and a priest at Clyfton." What the structure was like must be left entirely to the imagination, for nothing is visible to aid us, save perhaps it be a suggestion contained in the lay-out of the plan.

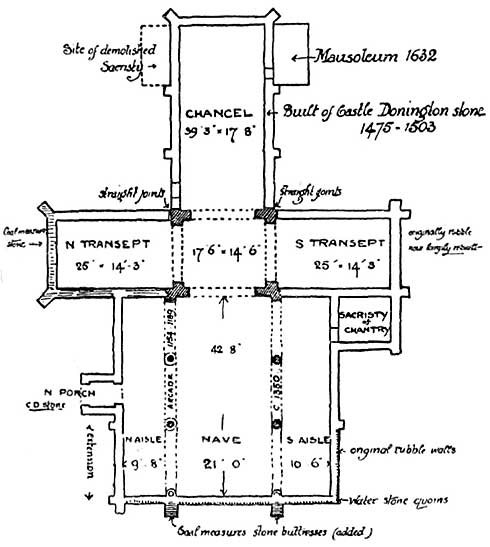

If we draw the plan of the church as it now stands we shall see that it is cruciform in outline, with a central tower rising from the crossing. The interesting point to notice is that the tower is not foursquare, but wider by 3ft. on the sides which face east and west. From this fact it may be inferred that the present tower stands on the lines of a pre-Norman building which consisted of an oblong nave, a square chancel, and a low tower set in the midst, after the well-known manner of pre-Norman churches, and this primitive plan formed the nucleus around which developments were added through consecutive centuries, until the simple parallelogram grew into a cross.

The first stage in development was the enlargement of the nave. This was accomplished by widening it, the side walls giving place to arcades opening into side aisles. The cylindrical shafts, and the square abaci to the capitals of the arcade on the north side, are characteristic of the work of the 12th century, while the pointed arches which they carry, with their bold roll mouldings and nail-head enrichments, indicate that the century must have been nearing its close when this work was carried out.

We know that a great wave of building activity swept across the county during the reign of Henry II., and it is interesting to compare the north arcade at Clifton with several other churches in a line with it— viz.:—Gotham, Attenborough, Ilkeston, which all appear to have been built or enlarged during this reign.

It is evident that at Clifton the widening did not satisfy the needs for any length of time and so a lengthening process was resorted to. The third and westernmost bay is found to be slightly different in treatment, and the "nail-head" enrichment is omitted.

I am inclined to think that the original western respond of a two-bay arcade was taken out, and re-set further westward to allow of a third arch being constructed ; its place was filled by a cylindrical shaft in correspondence with the earlier work, but having a cap, the abacus whereof follows a square line on three of its sides, but is octagonal on its western side. The outside walls at the west end and part of the south side, which were built as part of this extension, still remain. The rubble masonry of which they are composed, and the design of the windows, which, although recently restored, appear to contain much of the original material and follow the original lines, all point to the middle of the 13th century as the probable date when this extension was carried out.

Thus the church stood for another century, when the piety and munificence of a member of the Clifton family caused a chantry to be founded within the church. The exact date of the foundation is not known, but it was in existence in 1349.

The chantry altar would probably find a place at the east end of the south aisle for a time, but as needs increased, further accommodation would be obtained by throwing out transepts.

If we may judge by the style of the architecture, and the masonry employed, the south transept was built first; but subsequent restorations and alterations have interfered with the marks of identification. Nevertheless the remains of piscinas and almeries make it clear that an altar was here set up.

(1) No. 1.—Barton-in-Fabis. Vol. XXII Thoroton Transactions.