Cromwell not being content with this splendid pile, a new manor-house at South Wingfield was commenced sometime between the years 1440-1443. This new house, however, was never actually occupied by him, as the reversion was sold before completion to a compatriot, John Talbot, a famous captain, who, for his devotion and bravery in the French wars, was created Earl of Shrewsbury. Shakespeare, describing the diplomatic coronation at Paris in 1431, makes the king (Henry VI.) say:—

"A stouter champion never handled sword. Long since we were resolved of your truth, Your faithful service and your toil in war; Yet never have you tasted our reward, Or been reguerdon'd with so much as thanks Because till now we never saw your face. Therefore, stand up: and for these good deeds We here create you Earl of Shrewsbury."

He survived until the end of the Hundred Years War, but fell in the last battle, when France was completely lost, in 1453. As Cromwell outlived him by nearly three years, it would be the second Earl of Shrewsbury who became the actual possessor, and the first occupant of the new manor-house; and because it is known that he carried out some building work in altering the kitchens to suit his convenience, he is sometimes erroneously referred to as the builder of the house.

The Wingfield estate came to the Cromwells, as Tattershall had come, as the result of a lawsuit regarding the rightful heir. At an Inquisition post Mortem held at Derby in 1429, the Lord Treasurer claimed to be the descendant of the De Heriz family, through an alliance with the sister of Thomas Belers. After eleven years of litigation, the claim was successfully upheld against Sir Henry Pierpoint, a descendant of Sarah de Heriz and Robert Pierpoint. To give full details of all the lawsuits and alliances of the Cromwell family would be a long and tedious task. Suffice it to say that this case was decided in Cromwell's favour by 1440, and building operations were commenced shortly afterwards.

It is a far cry from Tattershall, in the fenland of Lincolnshire, to Wingfield, amid the rolling hills of Derbyshire; and although the two houses are contemporaneous, the difference in treatment is as marked as the difference in situation.

Wingfield manor-house stands upon a commanding eminence overlooking the Amber valley, dominated by higher hills, which separate it from the Derwent valley on its western side.

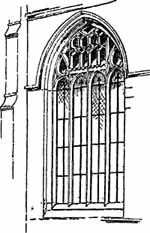

The name of the designer is not on record, but the similarity in the details to the work at Tattershall, as seen in the window tracery, etc., leaves little room for doubt that both designs emanated from the same source. There is no suggestion of French influence here, however, and beyond the fact that the house is semi-fortified, it has no special architectural distinction. It accords in every respect with the Perpendicular style of English architecture then current in the district, and well illustrates Ruskin's statement "that every dwelling-house in the middle ages was rich with the same ornaments, and quaint with the same grotesques which fretted the porches, or animated the gargoyles of the cathedral."1

The chief building material employed is crystalline millstone grit from Ashover Moor, four miles away. But for the effects of wanton destruction, the work still remains almost as sound as when it was built.

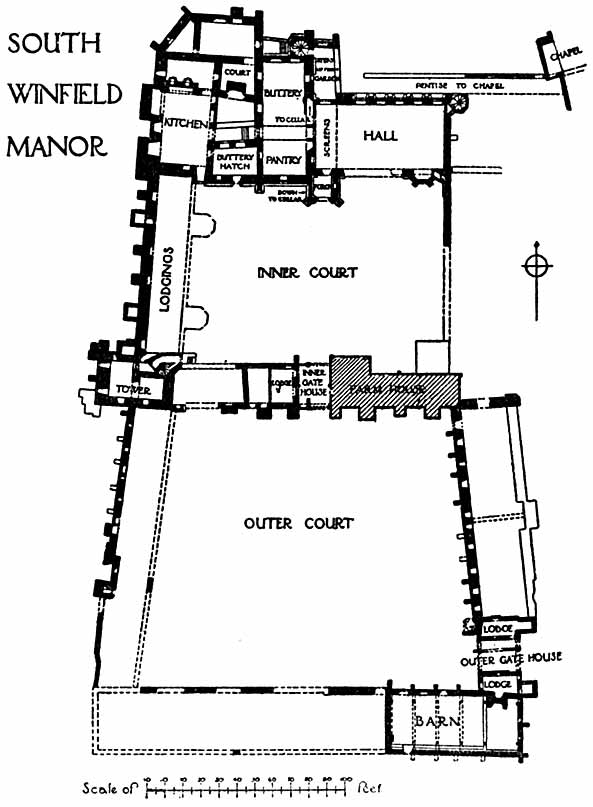

The buildings are ranged round two irregular quadrangles; the southern or outer court being devoted to guard-rooms, accommodation for retainers, and farm stock; the northern or inner court to the superior domestic apartments and necessary offices.

A wide gateway, having porter's lodge attached, gave entrance at the south-eastern corner of the outer court or "barmkin." As there was no moat, and consequently no drawbridge or portcullis, strong oak gates were fixed to both outer and inner archways. When these were closed and fastened for the night, entrance might still be obtained through the postern.

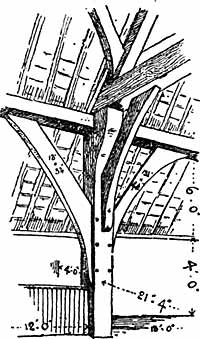

To the south of the gateway there is a large cow-byre and barn, having a fine oak roof of five bays. The eastern bay is a later addition, but all the rest is original work, and still in fine condition. The roof trusses centre at 14ft. They are 21ft. 4m. in clear span, supported independently of the walls, on oak posts, 13in. square, set 4ft. within the walls from either side. The stable buildings completed the south side, but these have all been swept away, while on the eastern and western sides nothing but ruined walls remains.

The inner gateway occupies a central position between the courts. It is similar in plan to the outer gateway. A panel over the archway on the south side contains "a treble range of stony shields," some large, some small, but all save two are blank. They were meant to be carved or emblazoned in situ, but as the house was sold before completion, the craftsman never got beyond the execution of two of the panels, which are carved in bold relief with the ever-recurring treasurer's purse.2 On the eastern wall, within the gateway, two small shields are carved on the base of a corbel, but these also are blank.

Eastward of the gateway, a portion of the ancient walls was adapted in 1774 to serve as a farmhouse, which is still in occupation. Some interesting furniture and pictures appertaining to the manor are on view within, together with mementoes of the siege during the Civil War.

To the west of the gateway, beyond the porter's lodge and guard-room, a tower, 72ft. high, forms a conspicuous feature in the composition. It is not machicolated, as at Tattershall. With the exception of loop-holes to command the gateways, the only defensive feature to notice is an "oeilet," for the discharge of arrows, from an ingeniously-placed position at the foot of the staircase commanding the entrance.

As at Tattershall, the circular staircase, giving access to the rooms at each floor level on the way, ascends in a continuous flight of 109 steps from the ground to the battlements. The strong tower would thus serve as a "look-out," and as a last resort in case of emergency or sudden alarm.

The whole of the western side of the inner court was taken up with domestic lodgings, of which the outer wall only remains above ground level. It would be difficult to find a ruin more interesting or more picturesque than this inner court. In the sunny days of early spring, the hazel catkins shine like sprays of gold, and the ground is sheeted white with snowdrops. In the early summer, the walls are clothed with sweet-scented wallflowers, and the woods around are blue with wild hyacinths. A romantic interest attaches to this portion of the ruin, for these are the apartments which were occupied by the unfortunate Mary, Queen of Scots. While a prisoner under the care of the sixth Earl of Shrewsbury, the queen stayed here for one night in February, 1569, again for about six months, commencing April of the same year, and again, after a lapse of fifteen years, in September, 1584.

During this visit, the accommodation at Wingfield must have been taxed to its utmost capacity. Including the queen's own household, the guard, and the retinue, at least 250 persons would be in residence. Amid such a crowd, spies gained easy entrance, and plots and intrigues were rife,3 so that in the following year (1585) the earl was fain to remove his fair captive to Tutbury. It was during the last stay at Wingfield that young Anthony Babbington, of Dethick, disguised as a gipsy, made the attempt to release the fair queen, which resulted in his attainder, and subsequent execution at Lincoln's Inn Fields, September 20th, 1586. Mary only survived him by a few months, her troubled career being ended at Fotheringay, in February, 1587.

The great hall occupies the north-eastern corner of the inner court. The open timber roof, and the central portion of the south wall have disappeared, but sufficient remains to indicate what a very fine apartment it once was. The great bay-window, which gave light to the high table, is equally graceful, whether viewed from without or within. The floor space is a double square, 36ft. by 72ft. The dais was at the east end, and the screens, with minstrels' gallery over, at the west end. The entrance from the inner court is through a porch, with a chamber above it. A staircase which gives access to the undercroft on the west side of the porch, has caused the angle buttress to work out very clumsily: the mistake is very noticeable in the uppermost weathering. The numerous sun-dials—there are two still left on the south front and one inside the gateway—were set up by Immanuel Halton, the distinguished astronomer, mathematician, and musician. He it was who cut out the tracery of the windows on the north side, and inserted plain stone mullions and transoms of Carolean type, in order to convert this fine banqueting hall into a two-storey dwelling, entered from the north, and here he took up residence in 1666.

The battlements of the hall are very elaborate. At Tattershall, and in all other parts of this building, the cap-moulding is on the horizontal lines only, but here it is continuous, and mitres round the outline of merlon and embrasure. The merlons, too, are each charged with a shield. In the centre of the porch, the arms of Cromwell and Tattershall quarterly are displayed. The cross of St. George is on the right, but on the left the merlon is now missing. The remaining shields are all blank. The parapet is further enriched with a continuous row of quatrefoils in squares, with a carved rosette in the centre of each quatrefoil.

Westward of the hall, and at a higher level, is the "parloir." The well-designed window in the gable is out of centre, but this may have been done intentionally, in order to obtain effect. Advantage has been taken of the slope of the ground to obtain a large undercroft beneath the hall. There is some doubt as to whether this was the retainers' hall, or simply a store-room: probability favours the latter. Whatever may be said to have occasioned the faulty setting out of the work above, there can be no excuse for the carelessness which is manifest here. The supporting shafts are not uniform in height, and the bold ribs of the vaulting fit badly on their abaci. There is a "vyse" in each of the four corners of the undercroft, so that the hall could be served in any direction.

Eastward of the hall, and on the lower level, fragments of masonry have been found which seem to indicate the position of the chapel, approached by a pentise from the vyse in the north-east corner of the hall. This view is strengthened by the fact that no trace of a chapel other than this has been found.

The approach to the gardens from the hall was through a charming porch and down a flight of external steps on the north side.

The buttery, buttery-hatch (with double arches for serving out meat and drink), and the kitchens are on this lower level, westward of the hall, approached through the screens. The present large kitchen was built by the second Earl of Shrewsbury, when he came into residence here in 1458-9, to replace the original kitchen, which was on the opposite side of the hall. In his agent's books of that date are accounts of workmen engaged in "plastering, roofing & mortaring the house &c."

The stone floor of the kitchen, the ovens, and three large fireplaces are still intact, save that in some instances the arches, which are in reality little more than cambered beams of stone, 13ft. span, have fallen away, leaving the "catenarian" arches, or arches of construction as they were called, to support the weight above—a practical testimony to the strength of that form of arch.

The manor was garrisoned for the Royalists, and besieged by the Parliamentarians during the Civil War. It capitulated July 20th, 1644, and was dismantled by an Act of Parliament dated June 23rd, 1646.

Thus it was at the command of a Cromwell, high in favour with his king, that these walls were raised, and after many vicissitudes, at the command of another Cromwell, having no connection but in name, at enmity with his king, that they were razed to the ground.

In addition to the works already described, the domestic buildings erected by Baron Cromwell include the hunting lodge, or "Tower-le-Moor," about four miles from Tattershall, and Colyweston manor-house in Northants.,4 of which only detached fragments remain.

The ecclesiastical work of the baron is more interesting from an architectural point of view than his domestic work. The church at South Wingfield was rebuilt while Cromwell held the manor, but the only portion of his work now remaining is the western tower.1 Here, again, the shields are left blank, but the work is analogous to the manor-house, and there can be no doubt about the authorship. The window in the western face of the tower is identical with windows in the south front of the manor-house; and, further, it is recorded that a quartered shield—Cromwell and Tattershall—was displayed in the windows at the east end of the aisles as late as 1770.

If we would see the "new style" of architecture at its inception, we must go to Tattershall again. The church stands about eighty yards eastward of the castle. The work of rebuilding was commenced before the castle was fully completed.

In 1439, Cromwell had made the church collegiate, and endowed it in support of seven priests, one of whom was to be warden, six secular clerks, and six choristers. Hence the need for extension. The style is characterized by the multiplicity of vertical lines, by the introduction of a battlemented transom in the tracery of the windows, by the employment of deep hollows or "casements" in the mouldings, and more than all by the absence of "featherings," or cusps. Excepting the stone pulpitum, which is a later addition, the work of a different school of masons, there is not a cusp to be seen throughout this extensive church.

According to Holles, who visited the church in 1642, there was then an epitaph on a stone under the central archway of the pulpitum, recording the fact that a benefactor of the college, Robert de Whalley, gave it in 1528. The stall work had been added by a nameless benefactor four years previously.

It has been the custom of those who follow Ruskin to speak slightingly of the loss of truth and vitality of this phase of English architecture. The Ven. Archdeacon Trollope, speaking of this very church, said "the inherent tameness of the ecclesiastical architecture of the middle of the 15th century is visible in this structure." We must always bear in mind that the church, as we now see it, is bereft of a warm glow of colour, which has left it looking cold and thin. In my opinion, the style was eminently suitable for its purpose. When we consider the demand for spaciousness and light, for paintings on windows and walls, it was the only logical outcome of the requirements of the time.

A panel in the gable of the north porch contains a shield of arms, which gives a clue to the identity of the designer:—

Fusilly ermine and sable (arms of the Patten family).

On a chief sable, three lilies slipped argent (Provost of Eton).

These are the armorial bearings of William of Wayneflete.5 It is known that he had a hand in building the castle, and it is more than probable that he designed the church.

He may have been assisted during the later part of his work by John Gyger, a warden of the college, of whom more hereafter. William Patten, better known to the world as William of Waynflete, the personal friend and executor of Baron Cromwell, was a man of great experience and repute in matters relating to building. No record of his birth has been found, but it is generally accepted that he was born at Wainfleet, Lincolnshire, circa 1400. He was a son of Richard Patten (Patin, Patern) or Barbors: for surnames were not fixed then as they are now, and consequently some confusion and uncertainty has arisen. When he was ordained deacon at Spalding in 1420, "he took the name of the towne he was borne in," in accordance with custom, and became known henceforth as William Waynflete. He received a liberal education. In 1443, he was appointed Provost of Eton, and it is not without interest that his term of office was coincident with the erection of the brick6 cloister of the college, 1441-8. In 1447 he was elevated to the Bishopric of Winchester, where he brought to completion the extensive work of his more famous predecessor, William of Wykeham, with whom he is sometimes confounded. During his episcopate, he built the bishop's palace at Esher (1470-80), a brick building, the counterpart of the work at Tattershall in every detail. In 1458 he founded Magdalen College, Oxford, the earlier portions of which were built by him, 1475-81. The contract between the founder and his master-mason, William Orchyerde, are still preserved in the college archives.

The famous Magdalen tower was not built until six yours after his death (1492-1505). It is said to have been designed by Wolsey, but the Wainfleet influence is manifest in the design. He also carried out additions to Merton College, Oxford. In 1484 he founded a grammar school at his birthplace. This will be referred to again later. He died and was buried at Winchester in 1486, where his tomb and chantry in the retro-choir of the cathedral are still lovingly preserved. His devotion to his tutelary saint, St. Mary Magdalen, is shown by the fact that his chapel at Winchester, his college at Oxford, and his school at Wainfleet were dedicated in her honour; while his position as Grand Master of the English Freemasons is a tribute to the estimation in which his work was held.

The rebuilding of Tattershall Church was carried out in Ancaster stone. The work is still in fair condition, clean, sharp, and beautifully weathered. The tower was built when the college was first instituted, and before the old church was pulled down. It is, therefore, a little older than the rest of the work. Between the head of the west door and the cill of the window above it is a range of blank shields. These oft-recurring shields are due to the fact that great importance was attached to heraldry at that time. Heralds' College of Arms was founded by King Richard III. a few years later (1484).

A bell-turret, on the south side, at the re-entering angle of nave and choir, is a feature of all the churches built under Cromwell's influence. It contains a staircase leading from the pulpitum to the roof; the means of ascent from the floor to the top of the screen being a "vyse" on the opposite side.

Lord Cromwell died January 4th, 1456, leaving direction in his will7 that he should be buried "in the middle of the Choir of Tattershall Collegiate church, until the said church is rebuilt, and then to be removed and buried in the middle of the new church, but so that no impediment be placed in the way of going in, or going out to those who minister the divine office in the aforesaid choir." The whole church was thus to become a chantry chapel, wherein the college was established for saying masses in perpetuity for the repose of the soul of the founder.

His wife had predeceased him by four months. Their effigies were engraved in brass, and fixed to a large stone (9ft. 7in. by 4ft. 3m.) placed over the tomb in the floor of the chancel before the altar.

This remarkably fine brass was terribly mutilated, circa 1672. The canopy was despoiled of some of the attendant saints, the head of the baron was removed, and the effigy of the lady was entirely destroyed. The remains of the monument have been refixed in the north transept. The great mantle is not a cloak of a Knight of the Garter, as some have supposed (Cromwell never was K.G.), but the civil costume of Lord Treasurer. The two "wodewoses," or hairy wild men, armed with clubs, which support his feet, are very curious. We do not know what they might signify here, but it is not surprising, in the light of recent events, that similar "savages" are found in the arms of the Emperor of Germany and the Kingdom of Prussia.

There are other brasses of first rank in the church, commemorating the treasurer's nieces, Joan and Matilda, and a nameless priest, who was a provost of the college, and died circa 1510. This is probably the John Gyger who was warden in 1443, and whom I have tried to identify as Wainfleet's building assistant.

The neighbouring village church of Ranby was also built by the Lord Treasurer, as the following inscription shews:—"Orate pro anima Dni Radulphi Crumwell . qui incepit hoc opus Ano Dni 1450:" but as the church has since been largely rebuilt, it does not serve as an illustration for present purposes.

The likeness between the Church of Holy Trinity at Tattershall, Lincs., and the Church of Holy Trinity at Lambley,8 Notts., is very striking. Without a doubt "the body" of the latter church, as it now stands, is the "new church and chancel" erected in accordance with the terms of the Lord Treasurer's will, and dedicated on the 29th April, 1480, as "the church within the church of Lambley, late wholly rebuilt."

The old tower, built during the reign of Henry III. (1216-1272), was left standing. The round arch, whereby it opened into the nave, was built up, and a doorway substituted. The western door of entrance was also built up with large squared stones, one of which bears the sacred abbreviation of the holy name.

An upper stage had been added to this old tower in 1377; also a vestry, with a chamber above it, on the north side of the chancel, and a rood-loft within the church. These were retained and incorporated with Cromwell's new work.

The vestry and chamber, of which only fragments now remain, were not identical with the chantry chapel founded by the sixth Lord Cromwell in 1340 (12th November, 14 Edward III.), as some have supposed, for this was said to be "in the body of the church." There is evidence of a chantry altar having been in position on the south side of the nave, or " body," before the rood-screen was set up, for the panelling and muntins are left unmoulded on this side from the base to the height of a reredos, and there is a deep mortise in the western face of the door jamb, such as would be made to receive the rail of a parclose. Further than this, two piscinae have recently been uncovered (1915) in the south wall, one at the east end of the chancel, near the high altar, and one at the east end of the nave, near the chantry altar.

(1) Stones of Venice, vol. iii., p. 97.

(2) It is said that the treasurer's badge was profusely carved on some of the woodwork of the interior, but this has long since been destroyed.

(3) Among the papers preserved at the Public Record Office there is a letter sent by Sir Ralph Sadler to Sir Francis Walsyngham, written at Sheffield Lodge, and dated August, 1584, wherein he says that he had entreated Lord Shrewsbury not to remove the Queen from thence to Winfield till Elizabeth had sent her orders, for he "had rather keep her at Sheffield with 60 men than at Winfield with 300."

(4) Leland said of Colyweston, "Bagges of Purse[s yet] remaine there yn the [Chapellje and other Places."

(5) His favourite verse from the Magnificat (St. Luke, i., 49) was added in Latin as motto:—"Qui potens est fecit pro me magna, et sanctum nomen ejus."

(6) There was a brickmaker at Eton in 1441 named William Veysey.

(7 Testamenta Eboracensia, vol. ii., p. 197.

(8) See Transactions, vol. xii., 1908, for illustrations.