Class A. Shuttered Openings.

Of all the examples I have noticed in the county, none can be said to be earlier than circa 1230. It is true there are indications of a "low side window" in the south wall of the chancel of the tiny Norman church at Littleborough, but here, as in so many other places, there is proof that the window was an insertion made in the old wall. It is to the "lancet" period, therefore, that we must look for the introduction of this feature in original work.

In some cases the string moulding beneath the window cills (which were always fixed high up, some six feet or more above the floor) was stepped, so as to allow the cill at the west end of the chancel, to be brought down to within three or four feet of the floor (Flintham and Keyworth), and the lower portion of this window opening was separated by a transom from the window above. In other cases the string moulding, or cill, is carried through level, and a small independent opening formed in the wall-space below the western window (Stanford-on-Soar). In either case the rectangular opening was fitted with a shutter, or door, hung to open inwards, with iron bands and hooks, like the door to an aumbry, and the iron stanchions and saddle bars were made to correspond with those to the window above; in many cases the iron hooks for the hinges and a slot or catch for the bolt are still in situ. Sometimes the hinge-hooks are on the eastern jamb, thus proving that the openings were not intended either for hagioscopes or lychnoscopes, as in these cases the shutter, when open, would screen the altar and the sepulchre from view, even supposing that the position of the openings and the direction of the splays were favourable.

It is equally certain that these shuttered openings were not intended to give light, or why should they have been so rigorously "stoned up." Light was more necessary after the Reformation than before, and it would have been a simple matter to have glazed the openings when the shutters were removed, as so many of them have been treated in modern times.

So far as I know, the only documentary evidence which throws any light on the question is contained in a letter written by Richard Bedyll, Clerk of the Council to Henry VIII., to Thomas Cromwell:".... and we think it best that the place, wher thes frires have been wont to hire uttward confessions of al commers at certen tymes of the yere, be walled up for ever." This letter will cause much confusion unless we are careful to distinguish between chancels where the parish mass was celebrated and chancels "in private ownership, or connected with a monastic establishment. It was specially written concerning a monastic church, and is only helpful to us when considering parish churches, in so far as it tells of "the little way they had" in those days of dealing with any object for which no further use could be found—it had to be "walled up," and "that use foredoen for ever." It may be that this letter was only meant to apply to openings in an internal wall, i.e. between a cloister and an aisle or a chamber. If external openings were included in its scope it would apply, for instance, to the church at Melton Mowbray, where four low side openings may still be seen in the outer walls of a large Galilee or western portal that was built as an extension, probably while the church was still in progress, or at any rate very soon after its completion (1300-1325).

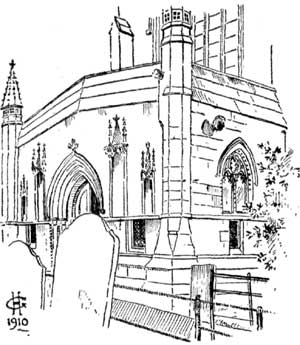

This fine cruciform church was partly built by Cluniac monks, who had a cell at Melton attached to the great priory at Lewes,1 and fourteen chantry priests were installed at the rectory at Burton Lazars, about two miles away, where in 1145 Roger de Mowbray had built a hospital for lepers. With such a supply of priests always at hand it may well be that this porch, with the openings in the walls, was intended to be used "for uttward confession of al commers at certen tymes of the yere," i.e. at Easter, Whitsuntide, Christmas, and during the patronal and dedication festivals. The openings originally had a wooden shutter inside and an iron grille or grating outside, and are convenient in all ways to be used as confessionals. They were blocked up with masonry, presumably at the Reformation; in 1856-7 they were opened out again and glazed.

But these special openings bear no relation to, and must not be confounded with, the openings in parish churches. If they were actually used as confessionals they only affect our question by shewing that the mediaeval workman knew how to meet the necessities of the case in the most convenient manner, and it would be a libel on his intelligence to suppose that the class of openings we are considering were the best means he could devise for communicating lepers or for confessing penitents. Besides, many churches still contain the "shryving pew," or "shryving stool," the place chosen by the priest at the opening of the chancel, or at a bench end at that part of the nave. Others, in the lower panels of the screen, have holes which may have been used as confessionals, although this is still a debatable point, since many authorities hold that these were simply "peepholes," to enable parishioners, as they knelt, to see the mass; and if it be urged that these were not introduced until a later date than the "low side windows," even so, in the early days the priest could, and did, confess penitents anywhere and everywhere; in the church, in the churchyard, or by the roadside, just as occasion served.

The fact that the openings were built up with stone indicates that the use they were wont to fulfil was discontinued when the Reformation was completed; and that it was not confession, for that did not cease at once, but something connected with the office of the mass. It is in this direction that we must look for the explanation.

I am afraid we do not realize in these days the great importance that was given to the ceremonial ringing of bells in the ancient Ritual. Harl. MS. 6970, fol. 241. November, 1314. The parish church of Blyth was placed under an interdict for not paying fees for reconciliation after pollution by the violent effusion of blood; so " when they said mass it was to be with closed doors, in a low voice, and without ringing of bells, the parishioners being rigorously excluded." The Inventories of church goods made in the reign of Edward VI. (1552) contain, in almost every case, a list of bells. Let me give a few extracts, taken at random, from the Returns for our own county.

Orston. Itm ij handbelles ij sacringe belles.

Itm iij great belles & a Sanctis bell.

Car Colston. Itm iij belles And a lytyll bell.

East Bridgford. Itm in the stepell iij belles ij hand belles.

Flinthatn. iij grette belles & a Sanctes bell, ij hand belles.

Sometimes the position of the bell is definitely stated -as—"j little bell in the churche, called the saints bell, the sacringe bell in the hie chancell."

As to the use of the bells during divine service, a few extracts from contemporary "Instructions" may be given.

Peter de Quivil, Bishop of Exeter (1280-1292). "The parishioners shall not irreverently incline at the Elevation of the Body of Christ but adore with all devotion and reverence: wherefore let them be first warned by ringing the little bell, and at the Elevation let the great bell be thrice knolled. Wilkins.2 I. 132." Alexander Stavenby, Bishop of Lichfield (1224-40) 1237. Walter de Cantilupe, Bishop of Worcester (1237-68) 1240. "At the last Elevation of the Eucharist when it is lifted up, let the little bell first be rung. Wilkins. 1. 641."

John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury (1279-94), 1281. "In elevatione Corporis Christi ab una parti ad minus pulsentur campanae."3 "In the Elevation of the Body of Christ let the bells be rung on one side at least {i.e. the side of the tower nearest the village) that the people who cannot daily be present at mass, wherever they be, whether at home, or in the fields, may kneel." (Lyndwood4 B. iii., tit. 23, app. 36.)

John de Anthona's commentary on the constitution, written in the 14th century, makes it clear that the tolling bell in the tower is here referred to, and not the little handbell.

References are also to be found in secular writings:—

"And at the last he (Sir Launcelot) was aware of an hermitage, and a chapel stood betwixt two cliffs, and then he heard a little bell ring to mass, & thither he rode & alight, and tied his horse to the gate and heard mass." And later a similar experience befell Sir Bors.—"La Mort d' Arthur," by Sir Thomas Malcore (Malorye) Knight in the reign of Edward IV., chap, x., book xxi.

(1) The Pipe Rolls, vol. 10, p. 13, contains a Confirmation by Ralph, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Lewes Priory, of all its churches and other possessions "in episcopatu lincoliensi habet ecclesias de fachestuna et de meltuna et cum terris." The portions of the church said to have been built by the Cluniacs are the middle part of the tower and the door to south aisle, 1130-50; chancel and Galilee porch, 1325; north transept and west window, 1330.

(2) David Wilkins, D.D., a German Swiss, born 1685, became Keeper of the Episcopal Library at Lambeth, and in three years drew up a catalogue of all the printed books and MSS. in that collection.

(3) The Latin quotation is frequently given thus:—"In elevationc vero ipsius corporis Domini pulsetur campana in uno latere, ut populares, quibus celebrationi missarum non vacat quotidie interesse ubicunque fuerint, seu in agris seu in domibus flectant genua,"—but the rendering in the text is a correct transcript.

(4) William Lyndewood, Divinity Professor at Oxford, temp. Henry V., Ambassador to Spain 1422, Bishop of St. Davids 1434, died 1446. Author of " Constitutiones Provinciales Ecclesiae Anglicanse."