Nottingham Castle.

Recent Explorations and some Historical

Notes

By F. W. Dobson

Nottingham Castle. Excavations of the site of King Richard's Tower.

A FEW years ago an account was given in the local press1 of certain excavations on the site of the so-called "Richard's Tower," which in July, 1904, was visited by some seventy members of the Thoroton Society.2

At that time little had been done beyond exposing pieces of the walls, and laying bare what remained of the brick-work midden on the south side. During the year 1908 the opportunity presented itself of disposing of the immense amount of rubble covering up these ruins, for the purpose of filling up the sloping land on the Lenton Road, on which the new estate offices of the Duke of Newcastle were being built, and over 200 cart-loads of debris were removed and these ruins opened out.

The date of the building of this colossal tower, perhaps the greatest and grandest feature of the mediaeval castle of Nottingham, has hitherto been a matter of contention and of doubt. Leland in the reign of Henry VIII. spoke of it as the work of Edward IV., a more modern antiquary has given it a date as early as that of Edward II.3

View of castle excavations, looking north-east.

Leland visited the castle between the years 1535 and 1540, or about sixty years after the death of Edward IV., so that what he heard there, would not be ancient history, but knowledge within the memory of men living at the time. We may take it therefore, that what he wrote would be fairly correct, and that these great "works and lodgings" as he called them, in the second court of the castle, were the work of Edward IV. I venture to suggest however, that the great tower itself, which would be the first stage in these additions on the north-west side, was commenced twenty years or more before Edward ascended the throne. In 1437 there was a commission "during pleasure to Geoffrey Knyveton (deputy of John Arden Clerk of the king's works) to take carpenters, labourers, masons, timber, shingles, tiles, boards, laths, lead, iron, glass and other requisites for the repair of Nottingham castle,"4 and six years later there was another commission to the same man, "to take stone cutters, carpenters, masons, plumbers, tilers, smiths, plasterers and other workmen for the building and repair of the Castles of Nottingham and Rockingham.at the King's wages, and to take stones, timber, iron, lead, glass, tiles, laths, shingles, boards, nails and other necessaries."5

All this goes to show that great alterations and additions were going on in the reign of Henry VI.; and we can imagine with what eagerness in the Wars of the Roses Edward IV. would seize upon this stronghold in the midlands, and afterwards make additions for the convenience and frequent residence of his court.

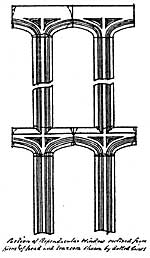

Moreover the beautifully finished and finely dressed masonry, the carving and mouldings of the stone-work exposed by these excavations, strengthen the belief that it was constructed in the period extending over the peaceful days of Henry VI. and not in the more troubled days of his successor, when the work would have been done in greater haste and in a rougher and a cruder way. We need not mention the name of Edward II. in connection with it. Sculptured masonry of the mouldings of doors and windows, string courses, window transoms and mullions, all show the characteristics of 15th century and Perpendicular work.

Portion of Perpendicular window restored from bead and transom shown by dotted lines.

The masonry of the walls, themselves now exposed, show the huge stonework with finely mortared joints of this later period. Someof these blocks measure more than four feet in length by two in breadth.

At the dismantling of the Castle in 1651, this great tower with all the other outworks and fortifications was demolished. Beyond the orders of the council of state6 giving the necessary instructions for this demolition, with orders for a troop of dragoons to attend, and particulars as to the future destination of guns and other articles of value, we have been unable to find any records giving an account of this transaction. There is no doubt, that it was blown up with gunpowder, for the huge cracks and fractures in the walls and stones give evidence of this. An account of the destruction of Eastwood Hall, in 1646, gives us a borrowed light on this method of destruction. After describing how this hall was bombarded with ordnance by a company of dragoons, without doing any great damage, the writer adds—"growing impatient they did put a barrel of gunpowder in the tower and at once destroyed more than half the hall and left the other in ruins, so that it cannot be repaired. They then sang a psalm and marched to the church."7

Robert Smythson, who, if not the actual designer of Wollaton Hall was the master-workman, and executed the chief detail of the building, took a plan of the Castle on the ground floor in 1617, which shows this tower to have been built on the plan of an octagon with five sides projecting beyond or outside the retaining castle wall.8 A very interesting feature, however, was revealed in the early stages of the excavations. The digging on the outer and south side of the tower exposed a piece of the mediaeval, probably late Norman wall lying beneath the present one, but branching off and running into the projecting south wall of the tower at an angle which showed that this structure had interfered with the old line of the castle area. By following out the line thus given and joining it to a line drawn from the angle of the wall showing at its northern end, it will be seen that the site on which the mediaeval builders raised this tower was in a great measure cut out of the second court of the castle (see plan).

When the demolition took place, the crypt or vault, lying many feet beneath the level of the castle court, became the receptacle for much of the masonry which thundered down from above; and when William Cavendish, twenty-five years later, began to build his residence, he used this north and north-west face of the rock, overlooking the present Lenton Road and Castle Grove—the line of the old dry moat—as a convenient "tip" for much of the unused rubble and masonry of the old fortress, and in time, vegetation completely covered up these ruins. Ninety years ago, the little spiral stairway leading down to the vault of this tower was partly unearthed, but this was all that was exposed of Richard's Tower till the recent excavations.

(1) Nottinghamshire Guardian, October

31, 1903 ; July 18, 1904

(2) Thoroton Transactions 1904, p.p. 39-41.

(3) A History of Nottingham Castle Emanuel Green, F.S A., the

Archaeological Journal, December, 1901.

(4) Patent Rolls. 16 Henry VI. m 19.

(5) Ibid. 22 Henry VI. m 8 d.

(6) State papers, domestic, 1651

(7) A History of Derbyshire, J. Pendleton, 1886. p. 277.

(8) I have recently heard that this original Plan which has been lost

sight of for many years is in the possession of Colonel Coke, of Brookhill

Hall, Derbyshire