The Old Streets of Nottingham.

No. II.

By James Granger.

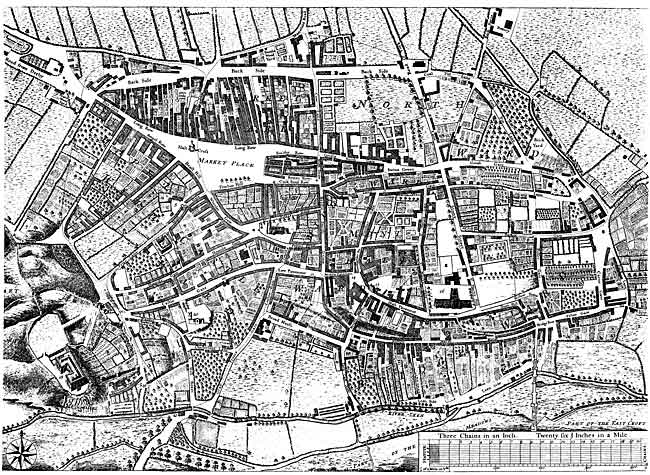

REFERENCES TO DEERING'S PLAN OF NOTTINGHAM.

1—Shoe Booths. 2—Hen Cross. 3—Queen Street. 4—Peck Lane. 5—White Friars. 6— St. Peter's Church. 7—Reservoir. 8—Collin's Hospital. 9—Mrs Newdigate's House. 10—Mrs. Bennet's House. 11—The House of the Hon. Rothwell Willoughby, Esq. 12—Johnson's Court. 13—Byard Lane. 14—Weekday Cross. 15—Charity School. 16—St. Mary's Church. 17—The Long Stairs. 18-Castle. 19—Bog-hole. 20—St. Nicholas's Church. 21—The Water Engine. 22—The Lead works, formerley Grey Friars. 23—Marsden's Court. 24—Penny foot Row. 25—The Summer-house of Langford Collin, Esq. [Click on image to download printable PDF version of the map].

IN his History of Nottingham (1748), Deering gives a list of about ninety thoroughfares; Gates, Streets, Lanes, &c.; and changes of names, though trifling in number when compared with recent times, had already commenced; yet it is questionable whether more than one well authenticated case can be specified (the top of High Pavement), where a street or other passage had been materially enlarged, before a number of the early years in the 19th century had elapsed. To most people this will satisfactorily prove how much more slowly our ancestors moved than we do.

In the old town, with a few exceptions, the avenues for traffic were generally narrow and uneven, and the roadways practically unmade, having no substratum. What we now term metalling, was then entirely unknown. In proof of these assertions I recommend my readers to carefully examine the illustrations of the streets, &c, to be found in Deering's History; but especially his "West View of Chapel Bar" (with the western end of what is now entitled Parliament Street), "Plumptre's Hospital as it appeared in 1750," "Collin's Hospital in Friar Lane" (now Park Street), "Ye County Hall as it appeared in the year 1750" (High Pavement), and a view of old houses near the top of Barker Gate.

The walls of buildings, &c, were frequently protected so as to prevent vehicles getting too near them. This will appear strange, until we recall the fact that at the beginning of the 19th century "Causeways," as we now have them, were unknown in Nottingham. Again I would advise my readers to notice the illustrations in "Deering," as regards this matter, and particularly that of "The New Change," in the Market Place, where the absence of causeways is conspicuous on the front and sides; also a portion of Long Row where the road for vehicles reaches to the shop pillars. When looking up the south side of "The New Change" it is just possible to see "The Hencross." This, except as regards the site, is probably the only illustration of it to be found in our old local histories.

The absence of causeways in former times, certainly allowed vehicles a full opportunity of utilizing the whole width of the thoroughfares, and considering the small size of the town, and trivial business then done, we must make a reasonable allowance in comparing what sufficed for our ancestors without causeways, with our requirements respecting width of streets in modern times. When the town felt the need of causeways and decided upon their formation, it was almost impossible to make them in some of the streets, &c, from lack of the necessary width, and generally those of an early date were narrow when compared with most in modern streets. On a large view of the Market Place, brought out at the beginning of last century, a country wagon is shown standing close to the pillars on Long Row. In our days this looks most incongruous.

It must not be supposed that the new-made causeways immediately assumed the finished appearance in which we now see them, for such was not the case. With many people still living, I can remember when half, and probably two-thirds, of the Nottingham causeways were paved with boulders ("petrified kidneys") and other materials, including a bedded sort of stone placed on edge (similar to what is burned for lime, I believe, at Barnston-in-the-Vale) which was rather pleasanter under foot. Some granite was then used, but the proportion was small. The Market place generally was paved with large selected boulders, having also rows of granite running from near Beast Market Hill and Angel Row to within a short distance of the Exchange. These were for a guide to those having stalls, when fixing them on Market days.

In the remembrance of myself and some of my older fellow-citizens, Bridlesmith Gate, as a business centre, was considered to rank as high, or higher, than any other street in the town, and I will give an extract from the "Nottingham Date Book" in confirmation thereof:— "1819, August. Bridlesmith Gate underwent a great improvement, the foot paths were formed of flagstones instead of boulders, as heretofore, the horse-road newly paved and by the voluntary consent of the tradesmen and owners of property, the whole of the numerous projecting signs, door-steps, &c, were removed. These alterations, with the newly introduced gas-lights, gave the street quite a new appearance. It being the most fashionable and best business street in the town, an attempt was also made to change its name to 'Bond Street' (the name of what was then one of the most fashionable streets in London), but the attempt was unsuccessful."

I am sure that many with myself will be really thankful to the people of that period for refusing to exchange the old and eminently historic name of Bridlesmith Gate for the unmeaning and inept title of "Bond Street." Respecting the "horse road" being "newly paved," I consider it probable that this was the first time such a desirable change made in the modern style had taken place.

Another notable event connected with the town occurred in 1819; for we are further informed that on "April 13 coal gas was first used in Nottingham to illuminate the streets; though the shop of Mr. Tatham, a brassfounder, was lighted five years previously, by an apparatus that made gas upon his own premises. The gasometer and works had been erected in Butchers Close as the site was then designated, on the premises formerly occupied as a worsted mill, &c, by Mr. John Hawksley.

"Only ten lamps were lit the first few days, viz., one at the top of Drury Hill, another at the summit of Hollow Stone, five in Bridlesmith Gate, and three in front of the Exchange. Attracted by the novelty of the sight thousands came out to indulge their curiosity; and numbers of the least informed of them scarcely dared to venture upon the pavement near the pipes, for fear of an explosion, or were lost in amazement at beholding flame exist without a wick."

The reference to the gas works being in Butchers Close will enable me to correct a strange error committed by the editor of the "Borough Records," vol. 5, p. 447, where he says—"Butchers Close .... Fletcher Gate."

He is referring to two statements in the same vol., the first on p. 178, where the Mickletorn Jury say on October 13, 1636, "Item, wee present the Leene for want of scowennge, against Eastcrofte, and Butcher's Close." This undoubtedly proves that Butchers Close, the "Leene," and Eastcroft, were closely connected with each other, and the Leen bounded the south side of the Close and north side of the Eastcroft. The next item is dated October 22, 1640, in vol. 5, p. 199, when the Mickletorn Jury say, "We present Jhon Hilton the baker, for not scowring the dike in Butchers Close. XIId." (fine). Here is full evidence that there was also a "dike" in or belonging to Butchers Close; and each of these extracts, written by the editor himself while compiling the volume named, conclusively proves, quite apart from other considerations, that Butchers Close was not, and could not be, "in Fletcher Gate."

The ancient name of what we now know as Fletcher Gate was "Fleschewergate," which is literally "Butchergate," but in the course of time, when bows and arrows had become obsolete, and the name by which the makers of the latter were known had lost its meaning, by some unaccountable circumstances, but no doubt very slowly, the title changed to "Fletcher" Gate, the equivalent to "Arrowmakers Gate," thus completely severing the old name from its root. Thoroton calls it "Flesher gate," and Deering says "Flesher Gate, by some Fletcher Gate."

The editor of the "Date Book," when referring as just mentioned to the first gas works in Nottingham, (1819) says they "had been erected in Butchers 'Close,' as the site was 'then' designated." This is inaccurate, for a new road was formed in that field running eastward for its entire length, and entitled "Butcher Street." This was quite at the commencement of last century, and no doubt a considerable time elapsed before "Butcher Street" was thoroughly accepted as the title, in place of "Butchers Close."

The fact can be proved by examining the poll books at the Parliamentary elections. In 1812 when voting, four persons said that they resided in "Butcher Street," and four in "Butchers Close." In 1820, according to the Poll Book, five said that they resided in "Butcher Street," and two only said that they resided in "Butchers Close." It was, therefore, incorrect to refer to that locality, or the site of the gasworks, as being designated "Butchers Close," for as shown the larger number of people entitled it "Butcher Street" at the period alluded to.

I regret to say that a number of unthinking persons have, during the last year or two, caused this old name of "Butcher" Street to be superseded by the ridiculous title of "Poplar" Street. Butchers Close had probably been owned by the Nottingham Corporation for 400 years, and by arrangements with them, the Butchers had been allowed to use the Close for nearly 250 years. (See "Date Book.") There can, however, I think, be little doubt that the agreement was drawn up in a loose, careless manner, from what afterwards took place, when, by an accident only, the town appears to have retained full possession of the field.

"1779, March 10th.—At the assizes this day a cause was tried before Mr. Baron Eyre, wherein Mr. William Baker, cordwainer, was plaintiff, and Mr. Munton, and other butchers of this town, were defendants. The trial was touching the butchers claiming the sole right of pasturage for their sheep in Nottingham Meadows (exclusive of the burgesses at large), from Martinmas to Candlemas. This they did by virtue of a bye-law of the Corporation, dated 1st of January, in the 27th of Henry VIII., which conferred the said right on them, and their successors for ever; on the condition of their paying four nobles per annum (originally 6s. 8d. each), in consideration of which the Corporation allowed them annually four loads of thorns; the wardens elected by the butchers, paying the expense of repairing the fences after each Martinmas.

In support of their claim the defendants produced several very aged persons, and sundry documents, and clearly established the fact that the 'nobles' had been regularly paid until within a few years of the trial. The record however setting forth that the butchers had paid 'and still continue to pay down to the present time, the Judge was clearly of opinion that they had failed in their case, as they had not chosen wardens for severa years, nor had they tendered the nobles to the Corporation. The jury returned a verdict for the plaintiff, with 1s. damages."

Here was a field with an old and most interesting history, which from 105 to 110 years ago was set out for building purposes, and a road made through its whole length, to the Beck rivulet, which in that part formed the boundary between Nottingham and Sneinton. The new way was appropriately termed "Butcher Street." In my young days I frequently walked down that street to its termination at the Beck, when I must either retrace my steps, or go a distance northward, and get into Pennyfoot Stile, Willoughby Row, or Fisher Gate. At that time, except by Pennyfoot Stile and a footpath across the fields, there was no other road in that part to Sneinton Hermitage and the Church.

I have the good fortune to possess an unique and large scale plan of Nottingham (Stretton) made from 108 to 110 years ago. For my purpose it is extremely valuable, explaining many most interesting points and matters, of which otherwise we should certainly have had little or no knowledge. At that period, there was a great deficiency as regards a good plan of the town, and Stretton's was doubtless the first to be taken of Nottingham on so large a scale as 100ft. to an inch. This, however, is not all, for a little before or after the commencement of last century the town began more earnestly (though not always wisely) to make changes in the names of various thoroughfares, &c, &c, and to form a few new ones, and as regards these points, the assistance rendered by the large old plan is eminently satisfactory.