Notes on Domestic Architecture of Old Nottingham

By MR. H. GILL.

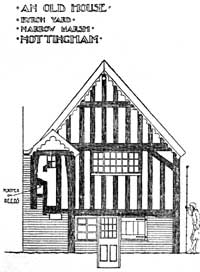

An old house, Byron Yard, Narrow Marsh, Nottingham.

“Nottingham is both a large towne and well builded for tymber and plaister.”

LELAND, A.D. 1540.

IN the early days of Nottingham an abundance of timber was obtainable from the great Forest of Sherwood and therefore the building of “frame houses” prevailed, i.e., houses constructed of stout oak framing consisting of uprights and cross pieces framed together and secured at the joints with oak pins, the spaces between being filled in with plaster or at a later period with’brickwork. This system of construction is variously called “magpie” or “half-timber work,” half the wall surface being black (timber), and the other half white (plaster), or “frost and petrel”-a corruption of frost (upright) and poutrelle (cross-beam). The more colloquial term is “stud and mud,” derived from the numerous references to “lattyng and daubing” with mud (i.e., clay) between the studs.

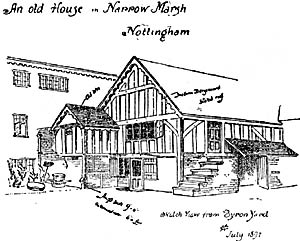

Very few of these “frame houses” have survived the inevitable march of modern progress. The oldest example I know at the present time in Nottingham is a house in Narrow Marsh. There is no documentary evidence to show when, or by whom, this house was built, but it is still referred to in the neighbourhood as the “Farm-house,” and this, together with the fact that the floor line is considerably below the level of the street, is evidence that it once stood alone upon the Marsh, long before any of the adjoining buildings were erected or any streets formed. The front portion of the building having been modernised and converted into a shop escapes recognition. It is at the rear in Kirk’s Yard, which is approached by way of Byron Yard, that the old work can be seen to advantage. As the space is too restricted to admit of the building being successfully photographed, I have been compelled to rely upon a line block illustration from a sketch made upon the spot.

An old house in Narrow Marsh.

The framing is composed of timbers, 6in. wide on the face, mortised and tenoned, and secured with oak trenails. The panels were all originally filled in with “plaister” on reeds, but some of them have been renewed with brickwork. The main roof was once covered with thatch, but this has long since given way to “swart cold looking slates,” a painful contrast with the old red tiles on the lower roof over “the dairy.” These tiles appear to be, if not original, of a very early date. Deering says that the first tiled roof in Nottingham—” the Unicorn Inn, the last house on the Long Row”—was put on in 1503, but numerous references in our Borough Records shew that tiles were being made and used for roofing in Nottingham more than a century before that date. For instance, in the year 1397 an action was brought respecting the quality of tiles used under “an agreement made in the 16th year of the reign of Richard II.,” i.e., A.D. 1393 (vol. 1. p. 349), and if the argument should be advanced that the tiles referred to may not have been roofing tiles it would only be necessary to cite the next reference to refute it; for it is recorded that seventeen years later an action was brought concerning the “engagement of Thos. Slater to tile houses,” A.D., 1410 (vol. II., page 71). “The Book of Dates” gives the year when tiles were first produced in England as A.D., 1246, but I find an earlier reference still in the “Chronicle of Jocelyn of Brakelond,” page 125, A.D. 1198, when Abbot Sampson “gave directions that the stables and offices in the court lodge round about the same,- formerly covered with reeds should be newly roofed and covered with tiles, under the supervision of Hugh the Sacrist so that thus all fear and risk of fire might be prevented.”

Another good example of a “frame house” is on Cheapside, but the modern shop front and the trade advertisements make it altogether unsuitable for illustration. This building, or its predecessor, is referred to in the Borough’s Records as “the tenement of William Babyngton esquire” (vol. II., p.p. 358, 416).

|

|

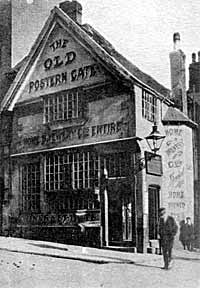

| The "Salutation" Inn. | The "Old Postern Gate" |

The “Salutation Tavern,” at the corner of Hounds Gate and St. Nicholas Street, a house and shop on the east side of Bridlesmith Gate, and the “Postern Gate” at the corner of Drury Hill and the Pavement, are the only other buildings of the kind that remain, although the last of these—the “Postern Gate,”—is not so ancient as at first sight it appears to be. It was rebuilt, some time before the Civil War broke out, upon the foundations of the old fortified gateway, that once guarded the southern entrance into the town, and it is interesting to note in passing, that at one time a constable’s box was formed in the thickness of the old foundation wall, on the west side of this house, with squint holes commanding Bridlesmith Gate and Low Pavement.

According to Deering the first brick house in Nottingham was built in the year 1615. This statement, although quite accurate, is apt to be misleading unless we keep in mind that the historian here distinguishes between the “frame houses” ‘that prevailed up to this time and houses built entirely of bricks or masonry.

To get to the days when bricks were first used as a building material, it will be necessary to go back a long way in the history of the world–long before the Israelites groaned under the bondage of Egypt–even to the time when Babylon was young and the cities that stood on the alluvial plains in the East were springing up into existence.

The Romans carried the art of brickmaking with them in their days of conquest and colonization. The bricks they used in this country are more like flat tiles than bricks, and are never more than 2ins. thick. The nave of St. Alban’s Abbey is largely built of Roman bricks from Verulam (size 143/4ins. X 71/2ins. X 13/8ins.), and they are practically as good and sound to-day as when they were made, fifteen centuries ago. As early as A.D. 886, the Saxons were using brickwork for their structures (see Brixworth Church, Northants.), but, as in the case of St. Alban’s, it is almost certain that the materials were obtained from a deserted Roman station.

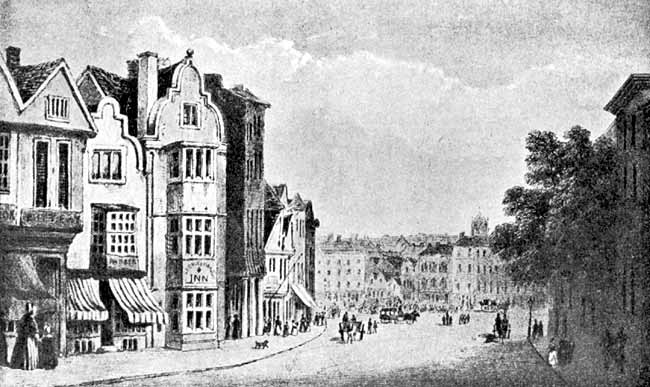

During the “Middle Ages” for some hundreds of years, the art of brickmaking was almost entirely lost in England. With the notable exceptions of Little Wenham Hall, in Suffolk, circa 1260, and Tattershall Castle, in Lincolnshire, circa 1440–built by Ralph, Lord of Cromwell and Lambley, the Lord Treasurer to Henry VI. –brickwork in our sense of the term–i.e., Flemish brickwork–was practically unknown until the time of Henry VIII., when the revived art of making bricks and terracotta reached an advanced stage of perfection. East Barsham Hall, in Norfolk, Hampton Court Palace, Eton College, and Sutton Place, near Guildford, are well-known examples of buildings erected during this reign. In the succeeding reigns of Elizabeth and James I., bricks were generally used for house building, and this brings us to our own earliest example, the “George and Dragon Inn,” at the west end of Long Row, distinguished by Deering as being the first brick house in Nottingham. The old house has been pulled down and rebuilt, but, by the kindness of Mr. James Granger, I am enabled to publish a view of “the lower end of Chapel Bar in 1845,” shewing the building as it was before any alterations were made.

The lower end of Chapel Bar in 1845.