Shelford church

BY Rev. J Standish

St Peter's church, Shelford in the early 20th century.

On reaching Shelford, the party assembled in the church, and the Rev. J. Standish read the following paper.

Journeying from East Bridgford to Shelford, by the higher road along the cliff, we cannot help being struck, as we approach this village, with the exceptional beauty of the valley of the Trent at this point; and with the effective position which the church and its massive tower hold in the landscape.

On reaching the church itself to-day, we are at once face to face with a modern restoration, undertaken in 1877-78. Mr. Christian was the architect; the cost of the restoration was £3,000 and the whole amount was defrayed by the patron and landowner, the Earl of Carnarvon. There was no clergyman in residence, no clerk of the works; and the builder seems to have been left largely to his own discretion, in the rejection and retention of details of the older work. We shall see that some of these, which might have been retained, have disappeared.

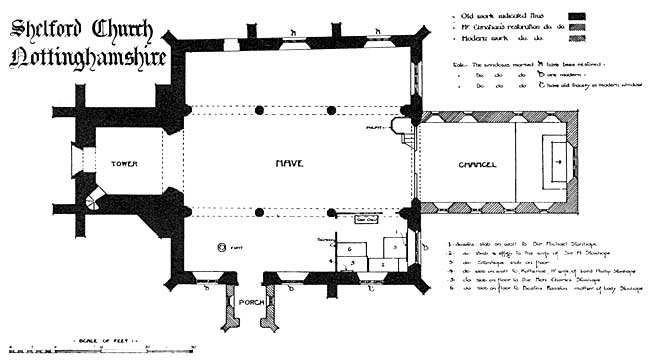

In September 1818, the church was visited by Mr. Stretton of Nottingham and I have been enabled to peruse the account he gave at the time, through the kindness of Mr. J. T. Godfrey, who has acquired the bulk of Mr. Stretton’s manuscripts. I have also obtained from Mr. Ellis of Sneinton, three photographs of the church prior to Mr. Christian’s restoration, and many details respecting the state of the church at that time. I have also had valuable help from Mr. Gleave, one of our architect members. He has very generously promised, for the Transactions, a detailed plan of the church on which he will indicate, as exactly as possible, what is old and what is new in the work of this church.

It consists of a clerestoried nave of three bays, north and south aisles, south porch, chancel and western tower.

The line tower was in 1818 much as we see it to-day, though its staircase in the south-west angle was in a very broken and dangerous condition and the tower itself bore clear traces of an episode in the civil war which I will relate later on.

Plan of St Peter's church, Shelford.

You will note that it is massively built in three stages, the highest stage being a little set back, within the central one. The tower is supported by a massive buttress at the east end of the north wall, and by rectangular weathered buttresses, at the north-west and south-west corners, which leap up in five stages almost to the very battlements. The eastern wall is strengthened by two smaller buttresses which are corbelled above the clerestory. At the east end of the south wall corresponding with the massive buttress on the north wall, there is a remarkable piece of masonry, strongly suggestive of a second staircase on this side of the tower. If however such a staircase ever existed, any further traces of it, have been hidden by the work of restoration.1 The west doorway in the tower is a beautiful one, deeply recessed, with mouldings of the late Decorated period; and above it we find a deeply recessed three-light window of the Perpendicular type. The four three-light belfry openings in the uppermost stage are also of the Perpendicular type; and the embattled parapet had originally eight pinnacles.

The belfry openings have louvre-boards. The middle stage contains clock and ringing-chamber for five bells. The present clock with quarter jacks was made by Cope of Nottingham in 1879; and it replaced an old one-fingered clock, the frame of which bore the inscription “R.R. 1680.” A note on the wall of the ringing-chamber states that this old clock was newly faced in 1837. Another item worthy of notice in the ringing-chamber is a fine stone-hammer with an iron suspension-hook in it; it formerly struck the hours, as they were ticked out by this one-fingered clock.

Now let me lighten the way by the story of an event in the civil war, recorded in connection with this tower, by Mrs. Hutchinson. Colonel Hutchinson, while engaging in an attack on the royalist garrison under Mr. Philip Stanhope at this village, found that his men could not quietly take up their quarters, from the fact that they were being fired upon by a detachment of the Shelford garrison, who had taken up their position in the tower and secured themselves from any attack, as they thought, by drawing up the ladders and bell-ropes and fastening down the trap-door leading to the belfry. Colonel Hutchinson, challenged them to surrender and threatened them with no quarter unless they did so; but his challenge and threats were alike disregarded. The tower long bore marks, and still I think bears some, of the clever manoeuvre adopted by the Colonel for bringing these sharpshooters down. He had heaps of straw placed on the floor of the church, under the tower, and the enemy were smoked out of their place of advantage like so many wasps.

The next point of interest on the outside of the church, is the north-west doorway. It is a small doorway with slightly pointed archway. Its date can be pretty closely arrived at from the fact that it possesses a very distinctive moulding known as the bowtell, or three-quarter moulding. Paley, in his “Manual of Gothic Mouldings” speaks of it, as “rather sparingly used in Decorated work; but as extremely common in Perpendicular.”

The nave windows are interesting on this north side, as being all different in respect of tracery, the original work in them being all of the late Decorated period and the tracery of the Curvilinear type (1360).

The south aisle had prior to Mr. Christian’s restoration, lost the tracery of its east and west windows in the south wall, while the central window was complete in this respect. A curious result accrued in this south nave, from the restoration. The two windows to the west in the south aisle became reproductions of the central window in the north nave, while the original central window of the south aisle was built in the easternmost bay of the new wall. Comparing the two easternmost windows in the two nave-aisles, you will find now, similar original tracery in both.

Coming to the chancel, one can only say that it was entirely rebuilt in 1877-8, and apparently on the lines of the Early English chancel, which we cannot but regret that it replaced. In 1818, Mr. Stretton speaks of this part of the church as possessing at that time six lancet windows which gave light, another lancet which was walled up, and an eighth window of three-lights placed at the south-end of the altar. This condition of things is shewn to some extent in one of Mr. Ellis’s photographs. The east window had prior to 1818 been gutted and modernized; possessed a circular head and was “plain, unmeaning and disgraceful.” This seems severe criticism; but it is fully borne out by one of the more recent photographs already alluded to. Mr. Christian’s east window was a triple lancet, inclosed under a chamfered arch, and had heavier mullions than the present longer window inserted and filled with stained glass by the present vicar, as a memorial to Mrs. Blanche Morse, his first wife. Both the stonework and glass of this window were designed by Mr. Kemp.

Below the east window of the south aisle and near the ground, is a stone, bearing the date 1677. It gives the date of the making of the Chesterfield vault which runs under the chapel in the south aisle. Before 1877, a portico of stone came out here, about six feet from the chancel wall; and underneath were two doors leading down to the vault. When the morning sun shone through the grating, Mr. Ellis tells me, that it was possible to see two of the coffins from the doors. Mr. Stretton speaks of there being nineteen coffins in the vault in the year 1818. About 1861, this vault was broken into by thieves, who stole the three coronets found on the coffins of the great Earl and his two wives. The plunder was of little intrinsic value, for the coronets were made of tinsel only. On other coffins were silver plates black with age; but these, either in their ignorance or their hurry, the plunderers left intact.

(1) This piece of masonry may have been built for support to the tower arid south aisle; but it is not possible to decide the matter, as the stonework within the church is covered with plaster.