Willoughby

A pleasant drive of about two miles brought the party to Willoughby-on-the-Wolds, a village situated close to the county boundary, and within a mile of the Fosse Road. Dr. Stukeley speaks of so many coins and Roman pavements having been dug up here, as to leave no room for doubt that Willoughby was a Roman station; but he erroneously identifies the place with Margidunum, which was undoubtedly East Bridgford. Willoughby was undoubtedly the ancient Vernometum placed in the itinerary of Antoninus as thirteen Roman miles from Ratae, now Leicester. Difficulties of identification with respect to some of these stations have arisen from the assumption that ad Pontem was one of them; but the solution seems to be that "ad Pontem" was, in the first instance, merely a marginal note directing wayfarers to the bridge (probably of boats) at East Bridgford, and that this note afterwards crept by mistake into the text of the iter itself. Another point of interest is the tumulus referred to by Throsby in his notes to Thoroton's history, under the name of Cross Hill. In the Ordnance Map the site is placed at a point where the road from Willoughby to Broughton intersects the Fosseway. About seventy years ago the inhabitants ransacked this tumulus, in quest of hidden treasure, and practically destroyed this interesting link with the past, without any advantage accruing.

Willoughby church, c.1910.

There seems to be much diverse opinion as to the dedication of the church at Willoughby. In the York records, it is given as All Hallows; in Ecton's Thesaurus as St. Peter; in Bacon's Liber Regis as St. Mary and All Saints; Thoroton gives All Saints; Throsby, St. Mary and All Saints; the Diocesan Calendar invariably St. Mary. In the testamentary burial of Hugh Willoughby, Kt., 15 Dre., 1448, he directed that he should be buried "in the Kirke before the altar of the Chantry of our Ladye."

On a board, at the west end of the church, are displayed the Royal Arms of King William IV.

In reference to the church itself, the following paper was read by the Rev. Attwell M. Y. Baylay, Vicar of Thurgarton:—

We have here a Parish Church of considerable beauty, and of exceptional interest. If we take its various parts in the order of their antiquity, we must begin with the two nave arcades, dating from the very beginning of the I3th century. They differ considerably from one another, as is very frequently the case, when, it may be, two benefactors undertook the cost of the two sides, and each employed his own gang of masons. They may also here be of slightly different dates, in which case we may look upon the south arcade as the older. The capital of one column has some beautiful and unusual ornamentation. Something similar has adorned the eastern respond on the same side, but is much mutilated. The western respond on the north side is keel-shaped in form. Next in date come the tower and spire, the latter being a characteristic and elegant example of the broad spire of this district. There has originally been no west door, and the existing west window is modern, but it is clear there has always been a small window in that position. In the tower are some old incised gravestones, which, I hope, when the nave is repaired, will be carefully preserved, and replaced in the paving. Note the ornaments on the corners of the tower where the spire joins it. Next we have the chancel, as evidenced by the chancel arch and the small remains of its original character in the northwest corner. Examination of the masonry convinces me that when built it was of the same great length and width as at present, a most unusual state of things at that date, viz., the opening years of the 14th century. Large chancels to Parish Churches seldom date back beyond the middle of that century. There must have been a reason for this at Willoughby, but I do not know what it was. The Perpendicular windows in the chancel are, of course, modern, and, I believe, do not pretend to reproduce what was there previously.

Next come the outer walls of the aisles, but even these are still early in the 14th century. It is possible that the original side aisles were narrower, and that they were widened when rebuilt by benefactors who founded chantries in their eastern ends.

Next comes the south porch, obviously later than the wall of the aisle, as shown by the joining, yet not much later. It is now in a sad state of ruin, but has been a fine and dignified piece of work. I see no trace of a holy-water stoup.

Then we come to the remarkable chapel of the Willoughbys, added, I suppose, about the middle of the 14th century. Observe, outside, the remarkable flatfaced tracery, which to me suggests that the bowl of the font is of the same date. Note the west arcade, and the small window over it, now blocked up. The reason of this arrangement seems to be that at that date there was a porch to the north door of the side aisle, the doorway of which can be seen on the outside. The arrangement by which the cill of the east window is cut away so as to give ample room for the altar, is most unusual. The central light of this window is so handled as to admit a panel to contain a painting or bas-relief, probably of the Patron, S. Nicholas. To the west of the beautiful piscina is a recess, possibly once forming a sedile for the Priest to sit in during the singing of the longer pieces of music at Mass. If so, it should shew that the Willoughbys maintained a chanter or two to serve this chapel, as well as the chantry priest. Some part of the stone altar still remains.

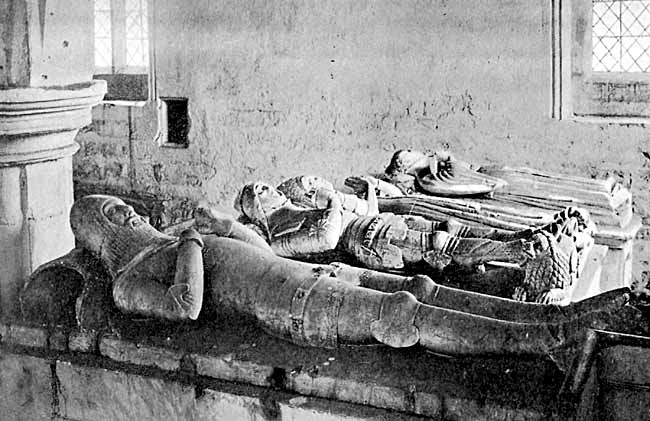

Willoughby tombs, Willoughby-on-the-Wolds.

The four effigies at the west end are older than the chapel, and have been moved into it, as has also, I believe, the large central tomb, which is itself later in date than the chapel. It is a most splendid and beautiful monument, and has been richly coloured and gilt. Note the crowned angels round it, the curious square scutcheons they hold, the exquisite carvings of the Blessed Trinity at the west end, and of our Lady at the east, suckling her Divine Child, and holding a posy on which settles the Holy Dove. Note also the two dogs at the feet of the female effigy. They are not hounds, but pet dogs with bells on their collars, and one of them gnaws the hem of the dress.

Next in date are the 15th century windows at both ends of the north aisle, and at the west end of the south aisle.

Lastly, the clerestory and nave roof, of the end of the 15th century or early in the 16th,—more probably the former—judging by the style of tracery in the spandrels of the timber roof, which contains in one of its bosses the monogram of our Lady.

We must not omit to notice the remains of old tile paving in the north aisle. They have been termed "monastic" tiles, but I do not know why. Those we see here, bear representations of the stag, the lion, and one has, I think, the alphabet,—not an uncommon subject on such tiles, and alluding, I suppose, to one of the ancient ceremonies in the consecration of a church, when the Bishop traced, with the foot of his pastoral staff, on the ash-strewn pavement of the nave, the alphabet in Greek and Latin characters, from corner to corner diagonally.

There is no trace of a rood-loft. Yet it is hard to suppose that a church like this was left destitute of one, and I believe that before the restoration of the chancel, traces of the screen still remained. But at all events the rood-loft here was one of those to which the ascent was by a wooden step ladder, as no trace of stone stairs can be found.

Just outside the chancel, on the north side, are remains of wall decoration,—an heraldic achievement above, and lettering below. It is in English, and several words can be deciphered, but I have not succeeded in making out the sense. I believe it to be of the time of Elizabeth, or later.

It is worthy of notice that the two westernmost bays of the north aisle, were for a long time partitioned off, and used as the Parish School. Such an arrangement indeed was not uncommon in old times.

The small remains of a village cross at the corner of the road to Widmerpool probably testifies to the Lords of the Manor having been at one time privileged to hold a fair here.

Let us hope that ere long the much needed repairs of the church may be carried out, and that by a wise and conservative architect, who will be careful to obliterate no trace of the past history of this most interesting building.

After Mr. Baylay's paper, Mr. George Fellows read the following notes on the Willoughby tombs, which are situated in the north chapel dedicated to St. Nicholas:—

The oldest monuments in this north chapel of St. Nicholas are those roughly carved in stone and lying on the floor at the west end of the chapel. One shows the effigies of two ladies of whom nothing definite is known; and the other the effigies of a knight and his lady, whom Mr. Godfrey in his book on the Rushcliffe Churches does not hesitate to identify with Sir Richard de Willugby (father of the Judge) and his wife. This view is supported by the fact that Sir Richard in his will, dated 31 Edw. I., appointed "his body to be buried in the Church of All Saints in Willughby, before the altar of St. Nicholas." He died in the year 1325, so this effigy is now 577 years old.

The altar tomb adjacent to the north wall of the chapel is that of Sir Richard Willughby, Knight, an eminent judge in the time of Edward III., who acted as Chief Justice when, according to Thoroton, "Le Scroop, the Chief Justice, was gone on the King's business beyond the seas." He married, as his first wife, Isabella de Mortein, the heiress of Wollaton, and thus the names of Willoughby and Wollaton became associated over five hundred years ago. This tomb is deserving of close examination, as the judicial robes are beautifully carved. In Stothard's "Monumental Effigies" an illustration of this figure is given, and "it is supposed to represent Sir Richard de Willughby, Chief Justice of the King's Bench in the II. year of Edw. III., in the legal costume of that period." The shields around the tomb are blank.

The conspicuous double altar tomb of alabaster, which occupies the middle of the chapel, is that of Sir Hugh Willughby, the judge's great-grandson. He married Isabella Foljambe, whose grave is under the floor-stone beside the tomb. The inscription on this floor-stone is now illegible, but according to Godfrey it was deciphered in 1781 as follows:—"Hic jacet Isabella quondam prima uxor Hugonis Willoughby . . . superior hic jacentis que obit XXIX Decembris Anno millmi CCCXVII. cujus anime Propitietur deus Amen." The date, however, 1317 is an error for 1417. His second wife was Margaret, coheir with her brother, Sir Baldwin Freville. She brought Sir Hugh the Middleton estates in Warwickshire. This alabaster tomb was orginally embattled, and is so represented in Thoroton's illustration. The detail of the carving is worthy of close scrutiny. The lower part of the tomb is surrounded by angels, each holding a shield; at the east end of the tomb is a representation of the Virgin and Child; at the west end a representation of the Holy Trinity. Both carvings are finely executed, and to a great extent have escaped mutilation. Sir Hugh died the 15th November, 1448, and seems to have been the last Willoughby who was buried here. At any rate, his son left instructions that he himself should be buried, at Wollaton ; and these instructions were carried out.

The alabaster tomb of a knight clad in armour, which lies under the arch dividing the chapel from the nave, is that of another Sir Richard de Willughby, who was son of the judge. He married a sister or a daughter of Lord Grey, and her arms appear on a shield on the side of this tomb. In the effigy he is represented as wearing a basinet with a camail of mail, a close fitting jupon, on which the Willoughby arms are shewn, an ornamented sword-belt and spur-straps, his feet in sollerets rest on a lion, and his hands are joined in the attitude of prayer.

Close by this tomb is the grave of Colonel Michael Stanhope, who was killed in the battle of Willoughby Field in 1648. A brass plate indicates the spot.

Willoughby Field, 1648.

The scene of the battle just referred to lies to the north of Willoughby Church. It was fought on the 5th July, 1648. In Mr. C. H. Firth's "Memoirs of Colonel Hutchinson," published in 1885, there will be found a description of the fight. When members had left the church for the north side of the churchyard, Mr. Fellows read the following summary of Mr. Firth's account:—

On Friday, 3oth June, 1648, a Cavalier force, consisting of 400 horsemen from Pomfret Castle and 200 foot, ferried over the Trent and marched towards the city of Lincoln; arriving there, they released out of gaol all the prisoners, felons and thieves, who joined their force; having done this they proceeded to the Bishop's Palace, which one Captain Bee, a wealthy citizen, defended for three hours, until the place was set on fire, when he made terms of surrender. It is alleged the Cavaliers immediately violated the terms of surrender, and carried off his goods, etc. How be it, Colonel Rossiter, who was at Belvoir, heard of these doings, and took immediate steps to pursue the Royalists. He got together some 550 newly raised men, and heard tidings of his enemies being in the neighbourhood of Bingham; on arriving there his force was augmented by another 150 horsemen. This considerably strengthened the Commonwealth contingent; his advance guard came in touch with the Royalists under Captain Champion, of Notts., causing both horse and foot to draw up in a large bean field at Willoughby, seven (?) miles from Nottingham. Rossiter, supporting his advance guard, decided to fight, although his opponents were formidably placed with the footmen "winged by horse, and those horse flanked with musketeers," and numbered among them many men of the best quality, as was apparent by their outward garb. Placing Colonel White in command of the right wing and Colonel Hacker of the left, with two reserves of horse in rear, he ordered a charge. A very stubborn hand-to-hand encounter resulted, neither side showing any disposition to yield. There was great disorder, and the two forces got intermixed; at length Rossiter's men prevailed, and he put his opponents to flight, capturing a large number of prisoners of quality, with colours, arms, and carriages. One hundred fugitives were taken in their flight towards Leicester, including Sir Philip Monckton, their general, who was brought to Nottingham by Mr. Boyer, High Constable, who took possession of and wore the sword of his captive.

During the first impact between the forces Colonel Rossiter lost his head-piece, was shot in the right thigh, and otherwise wounded, but he bravely kept the field until victory was complete, when he was conveyed to Nottingham. Colonel Hacker, the commander of the Leicester horse, was wounded, and Colonel White, of the Nottingham horse, had his horse much cut about. These two "merited much honour for their expressed valour."

The Commonwealth side lost thirty men killed, in-including a cornet, and Captain Geeenwood, commanding the Derby troop, was dangerously wounded.

Gilbert Byron, Major-General of the Royalist side, was taken prisoner, and about thirty gentlemen, and, it is said, about 500 prisoners and 100 slain, including Colonel Michael Stanhope, and many trophies, including "ten colours of horse and foot, whereof the greatest part in cloak bags were not delivered out."

The early history of Willoughby and its divers fees are given by Dr. Thoroton; but perhaps we ought not to leave the village without noting that it was here that Radulphus Bugge, the wealthy wool-stapler of Nottingham, gradually acquired much of the land. His posterity assumed the name of Willoughby as far back as the reign of Edward II., and added so materially to the previous possessions that "at last this lordship became almost entire" to this family. At length, in the reign of James I., Sir Percival Willoughby married Bridgett, the heiress of Wollaton, and sold his Willoughby estates to Sir P. Hutchinson. In 1790, the Duke of Portland and John Plumptre, Esq., were the principal owners, and there were then several resident freeholders; now the lands are still in the hands of various owners, of whom Major G. C. Robertson, of Widmerpool, is the chief.

As the party passed out of Willoughby village the base of the village cross was pointed out, and on reaching Widmerpool the company alighted near the church, which is charmingly situated in the well laid-out grounds of the Hall. Rev. A. J. Wood, the rector, met the party, but as a visit to this church was not contemplated in the original programme no paper was read upon it. The church has been very handsomely restored during the last fifteen years by Major G. C. Robertson, who extended his hospitality to the members, and also caused many objects of interest, such as books, pictures, etc., to be laid out in the billiard room for inspection. Unfortunately, time did not admit of a long scrutiny, and re-entering the brakes the party returned to Nottingham, which was reached at seven o'clock. The day was fine throughout.