Staunton and the Staunton Family

By George W. Staunton

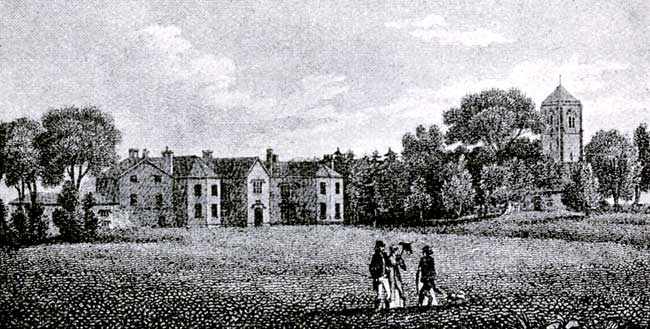

Staunton Hall and church in 1812.

Staunton before the Norman Conquest was the freehold of Tori and was held by Mauger, whose posterity, having their chief residence there, took their name from this place. This is Dr. Thoroton’s account of its earlier history, but the Harleian MSS. (No. 1555) mention Bryan, temp. 1047, the grandfather of Mauger as the first resident at Staunton. Mauger de Staunton, who held his lands by tenure of castle guard, defended Belvoir Castle against William the Conqueror, and evidently with a certain amount of success, as we find he was able to make good terms, being confirmed in the possession of his estate. Until the extinction of these feudal rights in the reign of Charles II., the owner of Staunton, being a minor, was by law, ward to the lord of Belvoir. Thus in 1604 we find Anthony Staunton ward to the Earl of Rutland, and by him given to Robert Dallington, who in turn lost him at a game of bowls to Sir Matthew Palmer, of Southwell, who married him to his sister Frances. This Anthony dying in the 27th year of his age, his son in turn became ward to Francis, Earl of Rutland, and was redeemed by his uncle Palmer for 200 Marks, and 100 more in case his grandmother (nee Disney) should die in his minority. In the rhyming pedigree of the Staunton family occurs the following reference to this tenure of Castle Guard and the defence of Belvoir:—

“At which same time the Mauger Knight

Thrughe feats of Arms and Sheeld,

In Marcyall prowe, so valeant was,

That then he wanne the Feelde.

In Belveor Castle was his houlde,

That Stauntones Tour is highte,

The strongest Forte in all that front,

And hiest to all men’s sighte.

Unto which Forte with force and Flagge

Ye Stauntons stocke must sticke,

For to defende against ye Foe,

Which at ye same coud kicke.

His lodgeinge large in that Turritte

At all times for his ease,

He may command both night and day,

An no man to displease.”

The presentation of the golden key of the Staunton Tower by the owner of Staunton to any member of the Royal Family visiting Belvoir is the last trace of this ancient tenure. We find William de Staunton “in consideration of high esteem and for the safety of my own soul and those of my ancestors and successors” making free Hugo Travers and his family because the said Hugo had assumed the Cross and journeyed to Jerusalem in the place of his master. The deed of manumission, together with the duplicate given to Hugo, are still preserved at Staunton. In 1324 Harvey de Staunton, Baron of the Exchequer, founded St. Michael’s House in Cambridge, now incorporated with Trinity College. He was buried under the choir of St. Michael’s Church, which edifice may, in the course of a few years, have ceased to exist by reason of the extension of Caius College.

The church at Staunton contains several specimens of the tombs of this period, but the effigies of the cross-legged knights with their wives were much damaged, and the two earlier ones entirely destroyed by Dr. Juxton, D.D., 1629, the Puritan Rector, who caused them to be demolished, as he said, to make room for his congregation, and (writes the Staunton of that day) “having no regard for gentility and venerable antiquitie paved ye streets with them. They were well cut in stone, lay in armour and cross-legged, but their inscriptions were worn out.”

St. Lawrence’s choir was the last resting place of the family, and while the church was being restored by the late Mrs. Isabella Staunton a knight’s breast-plate was discovered. This now hangs above the tombs. In 1446 Sir Thomas de Staunton left in his will a sum of money to build a second aisle in the church which should be dedicated to St. Thomas of Canterbury, but this donation was diverted from its proper use and spent in the repair of the roof. The rectory, which was demolished about fifty years ago, was built by Simon, brother of Sir Geoffrey de Staunton. It was a most interesting building, and the quantity and quality of the oak timbering obtained on its destruction are spoken of in the neighbourhood to this day. Its builder died in 1346, and the inscription on his tomb is given, with many others, in Thoroton’s Notts. The rectory had a large stone dovecote and a gate-house, of which no traces now remain. Three fields forming a portion of the Glebe land are situated in the hamlet of Alverton. They are known as the Golden Spur, and tradition says they were obtained in exchange for a knight’s spur.

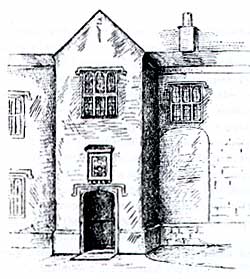

Staunton Hall. Entrance porch.

The hall is situated on rising ground close by the junction of two streams, the Devon and the Winterbeck. It had its watermill, as in the Doomsday Book is stated, and there were formerly traces of a moat on the north side, as well as still on the south. It stands in view of Belvoir Castle, and up to about 1860 it was the custom to supply annually a rope for the tenor bell of Bottesford Church, which is situated midway between Staunton and Belvoir; a custom no doubt originating in the ancient tenure above mentioned.

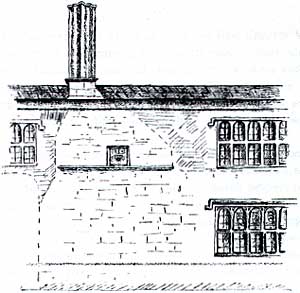

The house is constructed chiefly of the blue has stone, quarried on the estate, and evidently consisted originally, in main, of a long narrow house with octagonal towers at each end. In 1564, however, a porch was built by Robert Staunton who also erected a corresponding addition on the south side. His father Anthony had, in 1554, built a curious, star-shaped chimney to the dining hall and the mullioned window close by.

William Staunton, who held the property when the Civil War broke out, raised a regiment for King Charles and supported it at his own expense, which proved almost the complete ruin of his family. The Parliament soldiers attacked the hall and drove out Colonel Staunton’s wife and children, and quartered themselves there for some time. Amongst the family papers we find an authority bearing the signature of Oliver Cromwell, the date 1646, in which Mrs. Ann Staunton is allowed to look into and oversee the repairs needed after the destruction wrought by the soldiers.

Staunton Hall. Dining hall, shewing star-shaped chimney.

The oak front door still shows traces of the damage wrought by the field pieces of the besiegers, and it is locally said that the ancient table in the servants’ hall is made from the tree on which Cromwell promised to hang Colonel Staunton should he ever catch him.

This William Staunton distinguished himself at Edgehill and other fights, and was present at part of the siege of Newark. He died, it is supposed, in London after his return from the Continent whither he had fled, but strangely enough there is no record of the place of his interment, though his granddaughter, Anne Charlton, whose MS. contains many interesting details of her family, gives the inscriptions and places of burial of all her other relatives.

Major Staunton, who next inherited, still further diminished his patrimony in the extravagant times of the second Charles, and was succeeded by his brother Harvey, with whom the male line of this family ceased on his death in 1689. The property then passed into the hands of his daughter, Anne, the wife of Gilbert Charlton, of Ludford, in Shropshire, who, with her descendants and the late Rev. John Staunton, LL.D., made many alterations to the house. Amongst the most to be deplored are the removal of the oak panelling, changes made in the dining hall, which formerly was open to the roof with the usual galleries round, and the substitution of modern windows in many cases for the old stone mullions. Dr. Staunton, as he was generally named, was a squire of the autocrat sort and a pluralist of a type now happily extinct. He made many improvements, more particularly in the way of planting trees, but chiefly in a strictly utilitarian way.

During Dr. Staunton’s lifetime, Sir Walter Scott visited the place, and afterwards mentioned it in his book, “The Heart of Midlothian,” in the Abbotsford edition of which appears an engraving of the church and hall.

It may interest the members of the Thoroton Society to note that the Stauntons are lords of the manor of Thoroton.