< Previous

TAPPING A PROMISING DISTRICT :

Part 1: Sneinton's own branch railway

By Stephen Best

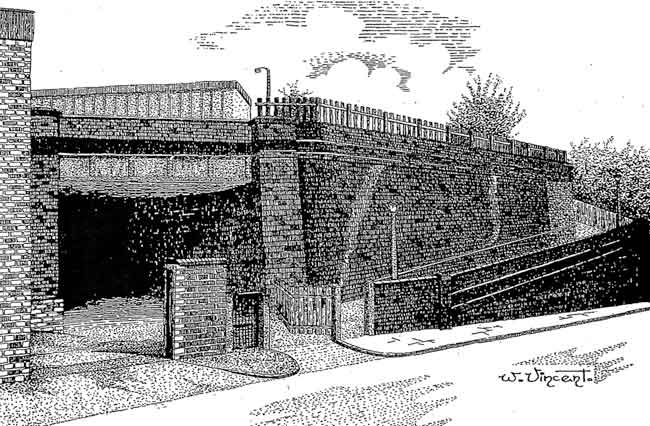

Remains of Manvers Street Station showing Cattle Ramp and Access Tunnel. Bill Vincent’s drawing, from Sneinton Magazine number 3.

Remains of Manvers Street Station showing Cattle Ramp and Access Tunnel. Bill Vincent’s drawing, from Sneinton Magazine number 3.NOT LONG AGO I WAS ASKED TO confirm or disprove something told to a friend by his grandfather. This old gentleman had recently insisted that there had once been a railway line ‘just behind Sneinton church,’ although his grandson was disinclined to believe him.

On being told that not only a railway, but also a station of sorts, had indeed existed here for almost eighty years, my acquaintance wanted to know where he could read about it. I had to reply that although a short account appeared in Sneinton Magazine more than twenty years ago, this is now difficult to find.

It struck me that almost a generation has passed since the appearance of that earlier article, and that over the intervening years memories of this unsung station have grown increasingly dim. Here, then, is a reminder of how a great railway company built just one wholly-owned line in Nottinghamshire, and how this short branch came to be in Sneinton.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the profitable business provided by many of the populous towns of England was keenly fought over by rival railways. Nottingham was no exception, and the county as a whole was to see helter-skelter competition for trade (often with coal as the main object) until the close of the century and beyond.

In the 1870s the Nottingham traffic was in the hands of the Midland and the Great Northern Railways, which owned stations here in Station Street and London Road respectively. At the end of this decade, however, another formidable company came upon the scene, when the London & North Western Railway gained a presence in the town.

1879 saw the opening of the LNWR’s joint line with the Great Northern from Saxondale Junction, on the latter railway’s Nottingham- Grantham line. The joint line ran through sparsely-populated countryside in south Nottinghamshire and east Leicestershire to Welham Junction, near Market Harborough. This may not sound a very lucrative undertaking, but the new route enabled the companies to operate through trains from Nottingham to Melton Mowbray and Market Harborough, in competition with the Midland Railway; and thence to Northampton.

The last-named town was in London & North Western heartland, and the LNWR had secured running powers from Saxondale over the GNR into that company’s London Road terminus in Nottingham, with the added right of using part of the station for dealing with goods traffic. Passenger traffic proved not to be a major source of income on the line, but, in the words of the Nottingham Evening Post of 16 May 1887, ‘the quantity of merchandise carried by the L. and N. W. from Nottingham to the stations on their main line, has of late grown to very considerable proportions.’

By the time that this newspaper article appeared, work on the Sneinton branch had already reached an advanced stage. What had happened was this. It being clear that there was no hope of improving goods facilities at London Road, the authorities at Euston, headquarters of the North Western, had quickly decided that a goods railhead of their own in Nottingham was imperative, and therefore presented the necessary Bill to Parliament in 1884. Like most railway companies then, and for many decades to come, the North Western derived most of its revenue from goods and mineral traffic, so it was quite natural for a goods-only branch to be considered viable. Railway Returns for 1884 showed that total receipts for the United Kingdom railway companies amounted to about £25½ million from passenger traffic, while goods traffic brought in revenue of almost £32 million.

Some three years later, in the May 1887 article already quoted, the Nottingham Evening Post reminded readers of the limitations under which the London & North Western were labouring in the town: ‘For a long time the inadequacy of the arrangements under which the company has been working, in regard to their Nottingham goods traffic, has been sorely felt...At present the company has possession of but a small section of the Great Northern terminus in the London Road for the reception of goods. Further space in that quarter being unavailable, the necessity for separate and larger accommodation has become exceptionally urgent; and the works now in progress at Sneinton meet, therefore, a distinct want.'

These works involved the building of a branch to a site selected by the LNWR in 1884 for its own goods station. This occupied about five acres between Sneinton Hermitage and St Stephen’s church: an area known locally as the Sand Rocks. Most of the land was owned by Earl Manvers, Lord of the Manor of Sneinton, and was at this date still undeveloped.

The job of preparing the ground for the goods station was a demanding one, and the LNWR must have felt confident that their financial investment would in time be adequately rewarded by receipts.

Work had begun in September 1886, the engineering difficulties being described by the Evening Post as ‘decidedly stiff.' The branch line leading to the new Manvers Street Station was about half a mile long, diverging from the Grantham-Nottingham line at Trent Lane Junction, which was situated on an embankment a few yards west of the lane itself From this junction the branch ran north-west, for about two thirds of its length on an embankment some 25 feet in height. The rest of the line was laid on the Sneinton sandstone rock.

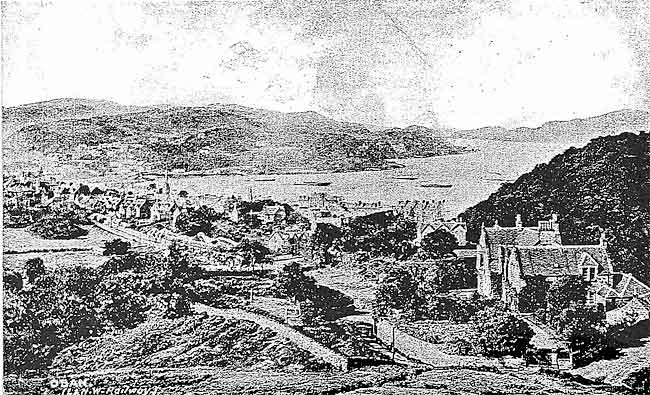

Sneinton and adjoining areas of Nottingham about 1917. The course of the Manvers Street branch can be seen lower right, with the goods station below and slightly to the left of the church.

Sneinton and adjoining areas of Nottingham about 1917. The course of the Manvers Street branch can be seen lower right, with the goods station below and slightly to the left of the church.Between Trent Lane and Meadow Lane the embankment crossed part of Lund’s Gardens. Lying behind handsome detached and semi- detached large villas which stood along the east side of Meadow Lane, this large area of allotments stretched up as far as Colwick Road. The newspaper reported that the gardens would be ‘entirely absorbed by the embankment, ’ (a statement which in the past misled this writer for a time,) but in the event some of the allotments were to survive for several decades longer. Early in the twentieth century one local market gardener and florist was still advertising his address as 41 Lund’s Allotments, and it was not until the council houses forming Hoten Road, Cosby Road, and neighbouring streets were built off Colwick Road between the wars that the last of the gardens finally disappeared.

The branch spanned Meadow Lane by means of a substantial single-arch brick bridge, built wide enough to carry five tracks. Only four were laid, however, the fifth being never required. The Evening Post considered the bridge ‘of good proportions.’ (The papers rarely seemed to report that a railway company was in the process of erecting an outrageous monstrosity in the town.)

The line, still on its embankment, ran just south of where Thoresby Avenue would be built - this had previously been an area of Great Northern goods sidings. Next, Sneinton Hermitage was crossed at an angle by an iron girder bridge. Some of Sneinton’s more picturesque sights became casualties in the course of the construction work, with the demolition of the ancient rock houses built into the Hermitage cliff, and lying in the path of the new branch.

The sandstone rock north of the Hermitage was reduced in height by about 25 feet by shot firing it, cutting the dislodged stone into manageable sizes, and removing the debris a few yards to form part of the embankment. The lower end of the old trackway known as Lees Hill had to be diverted to the route now followed by Lees Hill Footway.

The job of blowing up the top of the Hermitage rock proved 'extremely tedious,’ particular difficulties being presented by ‘the massive consolidation of the rock.’ Although the displaced sandstone contributed substantially to the new embankment, it was found necessary to augment it by hundreds of loads of material each week, carted to Sneinton from various parts of Nottingham.

The Evening Post report of May 1887 noted that about 120 navvies were currently employed on the Hermitage end of the branch. The necessity for removing the top 25 feet from the rock would entail the shifting of some 100,000 cubic yards of stone before the job was finished.

The most prominent structure at Manvers Street Station was a large goods warehouse served by four lines of metals, which ran right into the building. This consisted of basement,

originally expected to be used as a bonded store: goods platform: and first floor. On either side of the warehouse were three projecting crane hoods and a covered canopy, beneath which road vehicles could be loaded and unloaded. In the depot’s early years, of course, these were all horse-drawn.

Access to the warehouse was from Manvers Street and Newark Street. Although the latter was the main entrance, the official name of the goods station was always Manvers Street. An interesting and ingenious feature of the arrangements at the station was the inclined roadway from the lower (Manvers Street) entrance, which ran beneath the warehouse basement, permitting carts and drays to be loaded or unloaded directly through its floor.

From this lower entrance a sharp right turn led up to the cattle dock on the southern edge of the goods yard. Close to the Newark Street gate was a two-storey building housing the station offices. Nearby, essential for the working of the establishment for much of its existence, was stabling for twenty five horses.

The retaining walls on the side of the branch bounding the Great Northern Railway land had to be ‘of considerable solidity,’ and this requirement, together with the height of the embankment and the extensive excavations, added substantially to the cost of the works.

The bridges on the branch, and the retaining walls, were faced with Staffordshire blue bricks, the inside masonry being of Nottingham-made bricks. The Evening Post reported that many local men had obtained work in the building of the line, whose purpose had become something of a talking point in in the neighbourhood.

As was (and is) not uncommon, some Sneinton residents had got hold of the wrong end of the stick: ‘An idea has gained ground in the locality that there is to be a passenger station in Newark Street, and despite repeated contradictions, the notion is adhered to with strange perversity. As the particulars above show, however, the present purpose of the extension is limited to accommodation for goods traffic.'

The newspaper could nevertheless see further possibilities in the new goods station. ‘But the prospects which the undertaking opens up are decidedly encouraging. Indirectly the extension may help, in no small measure, to bring within the range of practicability the scheme for the establishment of a central station, which on all sides is admitted to be one of the pressing needs of Nottingham. ’

This was indeed a pressing need, which, 118 years later, has still to be met. Yet, had this plan for a Central Station been adopted, Nottingham today would look very different from the city we know.

Briefly, this was the background. Nottingham Corporation had been less than pleased that the Great Northern’s Derbyshire Extension had only skirted the northern suburbs of Nottingham, although it had provided Derby with a modem and reasonably central station in Friargate. Not only this, but while the Midland Railway had in 1880 provided Nottingham with a new fast main line passenger route to London via Melton Mowbray, those who travelled on it still had to put up with the uninspiring and inconvenient Midland Station in Station Street, opened in 1848.

Accordingly a memorial was drawn up in 1881 at the behest of the Council, incorporating a plan devised by the county surveyor Edward Parry, and his assistant. This was sent to the three railway companies which served Nottingham: the Midland, the Great Northern: and (by virtue of running powers over the GNR) the London & North Western.

Parry’s plan envisaged a site for a main station lying roughly along the course of Parliament Street, stretching from Market Street to Coalpit Lane (now Cranbrook Street.) Part of this huge site had already been declared an unhealthy area, unfit for habitation, so the property here would be coming down in any case.

It was proposed that a line should leave the western end of this station, tunnelling out of the centre of Nottingham beneath Wollaton Street, and eventually joining the Midland Railway at Radford. To the north another tunnel would run under part of the General Cemetery and a comer of the Forest, finally to link up with the Great Northern at Bulwell.

It was, however, the eastern aspect of the proposed network that interested the Post correspondent here. A viaduct would carry the railway out of the new station past Sneinton Market, until it reached Upper Eldon Street, about halfway up Sneinton Road. From here the railway was to disappear into a tunnel, emerging at its eastern end to join the lines to Lincoln and Grantham.

This was not all. From Eldon Street a branch would strike southwards in another tunnel, burrowing beneath a comer of Sneinton churchyard and passing under Sneinton Hermitage. It would link up with the Midland main line to London via Melton, immediately before crossing the Trent by what is now the Lady Bay road bridge.

Had such a breathtaking scheme ever become reality, a short line connecting the new Manvers Street Goods branch to this visionary network would have amounted to a mere minor adjustment. These were, however, years of intense competition, and the Midland, the Great Northern, and the LNWR were still more inclined to contend with one another than consider such a major act of joint endeavour.

The following decade, however, was to see a plan of equal magnitude carried out in Nottingham. This was the building of the London Extension of the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway (soon to be renamed the Great Central.) From the northern boundary of Nottingham at Bulwell to its most southerly point on the bank of the Trent, the new line, with its colossal Victoria Station, would transform what in 1897 became the City of Nottingham.

Victoria Station was originally to have been called Nottingham Joint Station, a name which reflected the belated act of important railway co-operation, by which the Great Northern had decided to combine with the MSL in the building of a joint station here.

Sneinton, then, was never to experience the massive engineering works which would have accompanied the projected Central Station in the 1880s. However, the new lines and structures entailed in constructing the approaches to Victoria Station in the late 1890s would, as described later, affect the neighbourhood drastically enough.

We return to the Evening Post report of 16 May 1887, into which a considerable amount of thought and research appears to have been put. The paper pointed out that, whatever might be ‘the stagnant condition of affairs elsewhere, ’ railway development in Nottingham was by no means at a standstill. The LNWR was stated to have laid out in excess of £50,000 on the Sneinton branch - equivalent to between four and five million pounds today. This still seems a modest amount, but labour costs were low, with an average wage of about 29 or 30 shillings (£1.45 or £1.50) for a working week far longer than that of today. By way of comparison, it may be mentioned that the new Nottingham Guildhall, built in 1887-8, cost £65,000.

The Post was keenly interested in the financial possibilities of the branch. ‘Railway directors,’ ran its report, ‘like the bulk of private individuals, are not so burdened with capital in these straitened times that they can afford to embark on doubtful experiments, and the authorities...may be safely credited in this matter with having well weighed the pros and cons. They are really tapping a promising, and to some extent, unprovided - for district. Important manufactories, of which that of Messrs. I. and R. Morley may be taken as an example are situate in the immediate neighbourhood, and the introduction of a new line of railway in close proximity to large productive concerns has a significance, the value of which is my no means limited to the expenditure involved. ’

The paper went on to emphasize how important to the LNWR the ownership of a station in Nottingham might prove: ‘Practically the undertaking merely gives the company extensive sidings and terminal accommodation, supplemented by a short and convenient line, but what is far more suggestive is that they are obtaining a separate footing and headquarters in the town, the importance of which is considerable in view of the possibilities opened up by this scheme. ’

The LNWR was a huge concern, regarded as ‘one of the largest, wealthiest and most respected joint-stock corporations in the world.’ For a period of some thirty years between the 1860s and 1890s the dividend on its ordinary stock never fell below 6 per cent. The company handled a vast amount of goods traffic; in Liverpool alone it possessed six goods stations. Although it might never catch the eye as a major player on the local railway scene, the company did establish another Nottinghamshire outpost, at Colwick. Here, rather overshadowed by the huge Great Northern locomotive sheds, the LNWR built its own depot in the 1880s, which remained open until 1932. The families of many of its staff lived in the nearby London North Western Terrace, but they always formed a small minority of the local railwaymen. Through its joint line with the Great Northern, however, the company succeeded in obtaining a share of the valuable coal traffic from the Nottinghamshire & Derbyshire pits, and from those in South Yorkshire.

Although many local men had found employment in building the Manvers Street branch, only one Nottingham firm had obtained a contract for any part of the works. This was G. Goode of Radford, the sub-contractor responsible for earthworks. Goode, of Guthrie Street, Old Radford, was listed in directories as ‘Coal merchant and contractor,’ which does not sound terribly reassuring. Presumably, though, Mr Hartley of Small Heath, Birmingham, in charge of the whole contract, knew what he was doing.

A Mr H.F. Perkins acted as resident engineer under Francis Stevenson, the LNWR’s chief engineer; the latter was regarded as a respecter of nature and of old buildings, who did his best to make his new works harmonize with the landscape. The other sub-contractors were from Birmingham and Liverpool.

By the summer of 1888 all was ready for the opening. The Nottingham Daily Guardian of 3 July was content to mark the occasion with a short paragraph, pointing out that although the first train into Manvers Street had arrived from London ‘and connecting branches ’ at 5 a.m. on Sunday, work had not actually begun there until Monday, when: ‘There was no formal opening of any kind. ’

The Nottingham Daily Express of the same day, however, did the new branch proud beneath the headline: ‘OPENING OF A NEW RAILWAY IN NOTTINGHAM.’ Several new details emerged from this report, which also amplified many of the points already made public: ‘The station is laid out for dealing with all descriptions of merchandise. A raised wharf has been provided in one part of the yard for furniture vans and other vehicles ...and a dock is being constructed for such traffic as requires ‘tipping.’ A 10-ton Goliath crane provides a ready means for dealing with heavy goods, and there are smaller appliances of a similar character in other parts of the yard.

‘The principal entrance to the station is from Newark Street, and it is upon this side that the station buildings, including an extensive goods shed...are located. There is also an entrance to the basement of the shed, which is the principal structure on the ground, from Manvers Street, this part of the premises being reached through an arched bridge, which carries the road above...The shed is about 215ft. long by 107ft. wide, and is a substantially erected and well- arranged building, composed to a great extent of concrete and iron, fitted with hoisting gear worked by gas engines, and generally possessing the appliances necessary for dealing with goods. The basement has been hewed out of the solid rock, and it is in contemplation to establish there bonded stores, for which the place seems well fitted. There is a loading stage there about 40ft. in length, and adjoining are two cellars, each 140ft. long and 50ft. in width.

‘Overhead is the shed, with which the basement is connected by an iron spiral staircase, large hoists also running from theloading stage to the premises above. There are four sets of rails into the shed, with extensive platforms adjoining each for dealing with the goods. The floor above this is adapted for storing grain or articles of general merchandise. There are facilities for hoisting and lowering goods by means of lifts in the shed, and extensive cages at the sides of the building where the wagons may load...The station buildings also include accommodation for the men, fitted with ovens, cupboards, &c.’

A London & NW Railway postcard converted into an advertisement for the station. The card dates from just before the Great War.

A London & NW Railway postcard converted into an advertisement for the station. The card dates from just before the Great War.

Traffic movements in the yard were controlled from a signal box (named Manvers Street), on the Lees Hill Footway side of the yard just north of the bridge over the Hermitage.

The office block at Manvers Street accommodated the goods agent in charge of the depot, Frederick Sissons, assisted by ‘a considerable number of clerks.' Also based here was William Bingham, the district superintendent, who moved from the LNWR’s town office in Lister Gate. In the course of time a mineral agent was also allotted to Manvers Street, presumably to deal with the movement of household coal.

Like other Nottingham papers, the Daily Express was keeping its eye on possible future developments: ‘The importance of the extension chiefly consists in the footing which it gives to the London & North Western Company in Nottingham, and there is no telling what may be the ultimate result of this small beginning.'

From the date of opening all London & North Western goods traffic in Nottingham was handled at Manvers Street. The initial traffic consisted of three trains in and four out daily, the depot establishing itself as a useful, if unspectacular part of the local railway scene.

Part 2 of this article will appear in the next issue. This describes later developments, the decline and closure of the line, and what remains of it today.

< Previous