< Previous

THE GENERAL AND THE PRIVATE:

Further revelations from Sneinton churchyard

By Stephen Best

SNEINTON IS ACCUSTOMED TO visitors from all parts of the world who come to see the birthplace of General William Booth. A less celebrated local General, however, was the subject of a question put to me some years ago.

I had led a guided walk as far as the churchyard, when one of the party remarked that she had once been told that General Wolfe was buried here, and asked whether this was true. For her pains she was greeted by derisive laughter from others present, and it gave considerable satisfaction to be able to reply that this worthy was indeed interred at Sneinton. It was, however, something of an anticlimax to have to explain that the occupant in question of Sneinton churchyard was not General James Wolfe, the hero of Quebec, and in fact not an army officer at all. Our General Wolfe was an ordinary resident of Sneinton, whose parents had chosen to distinguish, or encumber him, with this military Christian name.

The walk took place before the tidying up of the churchyard had been carried out, so most of the headstones which are now ranged along the wall were at the time lying flat on the ground, having years earlier been displaced from their rightful positions as grave markers. Here they comprised a sort of pavement on which youthful bikers practised their skills. General Wolfe’s memorial was one of these, and lay to the right of the path just inside the top gates. A rather plain Swithland slate stone, it read (and still reads) as follows:.

TO

THE MEMORY OF

GENERAL WOLFE

WHO DIED MAY 19th, 1849. AGED 53 YEARS.

ALSO SARAH

HIS BELOVED WIFE

WHO DIED DECEMBER 8th, 1854.

AGED 63 YEARS

Weep not dear friends and children dear

We only part a while

In hope to meet with Christ above

And see each other smile

Naming a child to commemorate a current or recent hero is, of course, by no means unknown. Indeed, a cousin of mine married a man whose middle name was Kitchener, his birth having occurred just after that famous field-marshal was lost at sea in 1916. It was, however, apparent from General Wolfe's headstone that he had been born nearly forty years after the death of James Wolfe in the moment of victory at Quebec in 1759. The latter was, astonishingly, only thirty-two when he died: a major-general with over 9.000 troops under his command. His name clearly retained sufficient lustre for at least one local family to perpetuate it through the nineteenth century.

While on this military theme, it may be mentioned that a Yorkshire and England cricketer named Major Booth was killed in action during the Great War. One cannot help feeling that had his parents chosen the Christian name General for him, rather than Major, all kinds of Salvation Army and Sneinton links could have been imagined. Since the age of popular ennoblement of jazz musicians, however, the world has become more accustomed to the adoption of ranks and titles as names or nicknames, and future generations of gravestone enthusiasts may one day be beguiled by finding the memorial of a tributary King Oliver, Duke Ellington, or Count Basie.

All this, however, is a flight of fancy, and irrelevant to our present purpose. It is General Wolfe we have to consider at Sneinton, and details about him, though scanty, are not without interest. He was a man of sufficient standing for his passing to be recorded in the death notices of the Nottingham press of the time, a very much rarer thing than nowadays. The weekly Nottingham Review of 25 May 1849 contains the following short announcement: 'At Sneinton, on the 19th instant, aged 53 years, Mr General Wolfe, wharfinger, Hermit Street.' Although the gravestone and newspaper announcement agree that Wolfe was 53 when he died, the Sneinton burial register gives his age as 54 - we shall see a similar discrepancy in the case of his wife. Son of George and Ann Wolfe, the young General was baptised at St Mary's church, Nottingham, on 19 December 1796. He was married in the same church in October 1822 to Sarah Bainbridge, a native of Pinxton on the Nottinghamshire-Derbyshire border.

The Nottingham Review was emphatically the paper read by Radicals in the town, and no mention of General Wolfe's death appears to have been included in the Tory Nottingham Journal of the same week. This may or may not have reflected Wolfe's own political opinions. From this brief notice, though, we learn that he was in trade, and probably self-employed; Lascelles and Hagar's Nottingham directory for 1848 confirms these details, giving exactly the same information about him as appeared in the paper. General Wolfe had, however, first appeared in local directories in 1834, in which year he is described as a coal dealer in Island Street, off London Road.

A few years before this, in 1828, the Chamberlains of Nottingham (elected annually to collect the income of the Corporation from its various properties and rights) had paid out £1.10.0 'to leading gravel to General Wolfe's Wharfe Road.' It was stated that this was for 'a new road from Leen Bridge to the Island.' Wolfe acknowledged receipt of the money by making his mark; notwithstanding his status as an independent tradesman, he was evidently unable to write his own name.

So a picture emerges of a man dealing in goods which could be carried on the canal. We already know that Wolfe was, at the time of his death, owner or keeper of a wharf. Several properties in Hermit Street backed on to the Earl Manvers Canal, the short branch which ran east to Manvers Street from the Poplar Arm of the Nottingham Canal. Island Street was equally well situated for canal-based trade, and some premises here, depending on which side of the street they stood, had access to the Poplar Arm or the Brewery Cut, which curved back round the north side of Island Street, and helped give it its name. Whether Wolfe dealt in coal to be transported by water we cannot be certain, but he appears to have been one of the numerous coal merchants in Sneinton and Nottingham, who met the insatiable demands of a crowded town in which virtually every home was heated by a coal fire. It is probable that General Wolfe lived on the northern side of Island Street, with the Brewery Cut behind his house; the maps of the mid-19th century show that nearly all of the domestic property on the Island was here.

Having found General Wolfe in the 1834 directory, the next step was to look for him in the census return for 1841, and here a couple of interesting facts came to light. First was evidence that he had a further string to his commercial bow, Wolfe being listed as a beerhouse keeper, still in Island Street. The returns show that he and his wife Sarah had three sons and two daughters, the children’s ages spanning some fifteen years. The second detail of note is that, although the two eldest sons Francis and William had escaped unscathed, the Wolfes' third boy, aged five, had followed his father in being saddled with the name General. We may conjecture that this little General Wolfe (also baptised at St Mary’s, in May 1836) grew up to curse the improbably youthful military hero whose name he enshrined.

Two local directories published in 1844 attest that General Wolfe was still running the beerhouse in Island Street, and one of these, published by Glover, adds the startling information that these premises were also called the 'General Wolfe’. No doubt any landlord so appropriately named would have been tempted to exploit this chance by trading under a pub sign called after himself. In this case, however, one suspects that the printer was guilty of a dittograph, since no other beerhouse listed here is given a name, and no evidence has been found elsewhere of a 'General Wolfe' beerhouse or public house in the town. Certainly, any compiler or printer, given a list of such premises with the name 'General Wolfe' included, could have been forgiven for thinking that this referred to the sign, rather than the proprietor.

Beerhouses had come into existence following an Act of Parliament in 1830, passed in order to discourage the selling of spirits. This Act permitted a householder to sell beer from his own house, on payment of a small fee, but originally with no requirement to obtain a licence or give evidence of his own good character. So popular did beerhouses become that within a year of their introduction there was one for every twenty families in England.

Sometime between 1844 and 1848 General Wolfe moved the very short distance from Island Street to Hermit Street, where he set up as a wharfinger. His death soon afterwards, in May 1849, meant that his widow, some years older than he, assumed charge of the business. The 1851 census describes Sarah Wolfe, widow, aged 64, as a wharfinger, and her eldest son, the 20 years old Francis, as a labourer. Young General Wolfe, at fifteen, was very possibly helping his mother at the wharf, although no trade or occupation is yet appended to his name. By 1854 Francis had become officially part of the management, Wright's directory for that year listing 'Sarah Wolfe and Son, manure merchants. Hermit Square,' among Sneinton’s tradespeople.

From coal dealing, then, the Wolfes had come to the carriage of manure, a commodity of which Nottingham had no lack. Not only were horses the almost universal motive power for road vehicles, but earth privies and middens were to be found appallingly close to the houses of most inhabitants of Sneinton and Nottingham. Piles of rubbish from cesspits and middens were usually removed from domestic premises during the night by manure collectors, the so-called 'muck majors', hence the term ’night soil’. Though some of it was carried directly into the country on collection from houses, to be used as fertilizer on fields, most of this filth was dumped on canal wharves, awaiting removal by barge. The removal of Nottingham's night-soil and rubbish was dealt with, often inefficiently, by private contractors until the 1860s, when the Corporation's Sanitary Committee decided to take responsibility for carrying out this vital task. Sneinton, however, was not included in the Borough until 1877, and individual collectors appear to have muddled along here as before for the time being.

Sarah Wolfe died in December 1854; her age, as given on the gravestone, does not tally with the census, which suggests that she was about four years older. As with her late husband, there was evidently some doubt about her age, and we have no way of knowing which was correct. Sarah was born almost half a century before registration of births, marriages and deaths came into force, and she, let alone her children, may well not have known her exact date of birth.

The 1861 census shows Francis Wolfe as a 'wharfinger: dealer in manure &c.' at Hermit Street, while his younger brother General Wolfe junior is now a married man of 25, with a wife (née Sarah Richards) and young son. He has moved the short distance from Hermit Street, and now lives in Carrington Place, off Lower Eldon Street, Sneinton. In the census General Wolfe describes himself as a 'labourer (night soil)'; it seems probable that he was now working for his elder brother at the wharf in this essential and hazardous, but far from glorious trade. The family of General Wolfe had certainly taken up a malodorous way of earning a living, and one wonders what the victor of Quebec might have thought of his name being borne, a century after his own death, by someone following such a calling.

Francis Wolfe appears again in the 1864 directory as a manure and straw dealer. He may, however, have wearied of the manure business soon afterwards, as by 1869 he had returned to another of his late father's occupations. For a brief period Francis was licensee of the Red Lion public house at the town end of London Road, just where it became Red Lion Square. By the early 1870s, however, he has drifted out of view.

Though he is not a central figure in this story, we must for a little longer follow General Wolfe's son, General junior. He and his family are next found in the census of 1871, now living with Mrs Wolfe's mother in Stanley Terrace, off Lower Eldon Street, just across the road from I. & R. Morley's enormous hosiery factory which lay in the triangle between Newark Street, Manvers Street and Lower Eldon Street. From Stanley Terrace the Wolfes would have had a terrifying grandstand view of the disastrous fire that gutted the factory in 1874. His occupation now described simply as labourer, General Wolfe lived only a hundred yards from his home of ten years earlier. His three sons were, no doubt, all mightily relieved that they were called, respectively, Arthur, Frederick, and James, the portentous name General Wolfe having been visited upon none of them.

The 1881 census shows the younger General Wolfe to be still a labourer. He and his family have, however, moved house again, and now live just around the corner from Lower Eldon Street, in Hampden Place, off Beaumont Street. They are at this same address a decade later, and so we have our final glimpse of him at Hampden Place in the 1891 census; the 56 year-old General Wolfe junior has by this date risen in his trade, being now a foreman at the Health Department. In the light of his previous employment, it must be likely that he worked at the Nottingham Corporation Sanitary Wharf and Health Depot, at East Croft, London Road, and was still engaged in the disposal of night soil, which continued to be sent out of Nottingham by canal until the early decades of the present century.

The reader may well reflect that, in beerhouse keeping and night-soil disposal, the two General Wolfes could have hardly followed more contrasting occupations. There can be little doubt which was the more congenial, but equally little argument as to which was the more necessary for the health of the community.

SALMON’S MAP OF NOTTINGHAM, 1861, with numbered locations of places mentioned in this Article (1) Island Street, and (2) Hermit Street, where General Wolfe senior lived and had his businesses: (3) Carrington Place, (4) Stanley Terrace, and (5) Hampden Place, where General Wolfe junior lived: (6) Pierrepont Street, home of James Skinner: (7) Actual burial place of General Wolfe Senior: (8) Present site of the Wolfe and Skinner gravestones.

SALMON’S MAP OF NOTTINGHAM, 1861, with numbered locations of places mentioned in this Article (1) Island Street, and (2) Hermit Street, where General Wolfe senior lived and had his businesses: (3) Carrington Place, (4) Stanley Terrace, and (5) Hampden Place, where General Wolfe junior lived: (6) Pierrepont Street, home of James Skinner: (7) Actual burial place of General Wolfe Senior: (8) Present site of the Wolfe and Skinner gravestones.[Click on the map for a larger version suitable for printing]

None of the places lived in by the Wolfes now survive. Island Street has been twice transformed, first by becoming progressively encroached upon from the 1880s by various departments of Boots factory. It continued to exist for many years within this Boots enclave, but no private houses were left, and the street ceased to be a public thoroughfare. At this time of writing (Spring 1998), what is considered by many a piecemeal and characterless total redevelopment of the site - now 'The Island Business District’ - is under way. The opportunity of retaining some of the canal-side buildings, and of perpetuating the historical significance of the area, has been insensitively squandered.

The old Hermit Street, also engulfed by Boots many years ago, ran from Manvers Street to Poplar Street, and its site now lies beneath the other end of this same redevelopment. In it stood the former Sneinton Public Offices, from which the parish was administered before becoming part of the Borough in 1877. These premises continued to serve the community until 1928 as Sneinton Public Library and Reading Room, and were finally occupied by Boots Chemical Department Microanalytical Section. Writing in 1949, a local correspondent recalled that this building stood on the exact site once occupied by the entrance to General Wolfe's canal wharf.*

The site of Carrington Place is over the road from Sneinton Health Centre, on the side where where the Project Pehchan building and Millview Court now stand. The old street pattern between Sneinton Road and Newark Street was seriously obscured by the wholesale clearances of the late 1950s and afterwards, so the precise spot is not easy to identify. Stanley Terrace, also off Lower Eldon Street, is, as already indicated, simpler to locate. It was one of three terraces off the eastern side of the short stretch of Eldon Street between Newark Street and Manvers Street. Empty premises, lately used by BICC, now occupy the site, facing the sadly reduced remnant of the former Morley's factory. Hampden Place ran towards the back of properties in Sneinton Road from the north side of Beaumont Street, quite close to the Notintone Street end. Its site is nowadays marked by houses which stand in the remaining stub of Beaumont Street at the rear of the William Booth School.

Not only have the homes of General Wolfe, father and son, all disappeared, but, as mentioned at the start of this narrative, the headstone of the elder General no longer marks his burial plot at Sneinton. In common with many others in the churchyard, it was unnecessarily moved sometime during the 1930s, but there is little point here in lamenting over milk spilt so long ago. The stone can now be found attached to the churchyard wall, about thirty yards to the right of the main gateway as you go in. Like all the other gravestones ranged along here, its inscription is well worth seeking out and reading. By a lucky chance, however, a photograph was taken in the churchyard between the wars, just before the upright stones in question were displaced from their original sites. Happily, the Wolfe headstone is the main feature of this photograph, and from the lie of the ground in the picture, and the neighbouring gravestones visible, the spot can be pinpointed exactly. Stand with your back to the west wall of the church, with two headstones of the Jelley family just on your left. Beneath the turf immediately in front of you lies General Wolfe, sometime beerhouse keeper of Island Street, wharfinger of Hermit Street, and father of General Wolfe, night soil labourer.

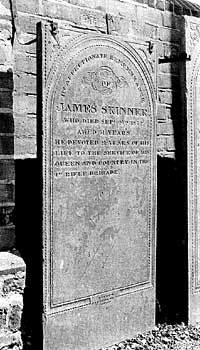

Although Sneinton’s General Wolfes were never military men, a very real soldier is commemorated by another slate headstone, some fourteen places along the churchyard wall from Wolfe's stone. Here we find the following inscription:

IN AFFECTIONATE REMEMBRANCE OF

JAMES SKINNER

WHO DIED SEPr. 27th. 1872

AGED 51 YEARS

HE DEVOTED 21 YEARS OF HIS

LIFE TO THE SERVICE OF HIS

QUEEN AND COUNTRY IN THE

1st. RIFLE BRIGADE.

James Skinner first appears in Sneinton in the 1861 census, living with his wife Ann at the Pierrepont Street house of her parents William and Elizabeth King, the former a labourer. Then aged 40, Skinner is described as 'pensioner.' Further detail emerges from the census of 1871, not long before James Skinner's early death. By this time he is at the Boar’s Head beerhouse in Pierrepont Street, his occupation given as 'beerhouse keeper/Chelsea pensioner.' Clearly Skinner was not living as an inpensioner at Chelsea Hospital, and the phrase 'Chelsea pensioner' was being used here, as was often the case, to denote an out-pensioner who had served in the Army.

War Office documents reveal that in 1839 the eighteen year-old James Skinner, born in St Mary's parish, Nottingham, enlisted in the Rifle Brigade at Daventry, Northamptonshire. The thorough nature of Army records gives us a physical picture of James Skinner that we do not have of General Wolfe. Five feet seven inches tall, and of fair complexion, Skinner had hazel eyes and brown hair, and was at the time of his enlistment a labourer. Twenty one years in the Rifle Brigade would suggest service in several different parts of the world, and indeed his record confirms this. Skinner spent over half his time in the Army on overseas postings; five years and seven months were spent in Malta and Corfu**, and a further five and a half in the Cape of Good Hope. Here he took part in the Kaffir Wars of 1846-47 and 1852-53, and was present on 20 December 1852 at the action against the great Basuto chief Moshesh. In addition to a campaign medal for South Africa, Private Skinner received the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal, with a gratuity on discharge of £5. His service record was 'very good', and during his Army career Skinner was only once in the defaulters’ book. This was probably sometime in 1857, when, after just four months as a corporal, he reverted to the rank of private.

The regimental board, held at Winchester in November 1860 to confirm James Skinner's honourable discharge from the Army, was presided over by a member of another Nottinghamshire family, whose background was as different from Skinner's as can be imagined. This was Captain Lord Edward Pelham-Clinton, second son of the 5th Duke of Newcastle. In later life he was to become a colonel in the Rifle Brigade: M.P. for North Nottinghamshire: Groomin-Waiting and Master of the Household to Queen Victoria: and Groom-in-Waiting to King Edward VIL Skinner's signature to his discharge document shows that, unlike General Wolfe, he was capable of writing his own name very legibly.

James Skinner must have been very proud of his Army record. It is striking that, while pride of place is given on his gravestone to his service in the Army, no mention at all is made of any member of his family.

Like General Wolfe’s beerhouse, James Skinner's Boar's Head has disappeared, although it remained open in Pierrepont Street until that part of Sneinton was comprehensively redeveloped in the late 1950s. It stood close to the lower end of Pierrepont Street, just above its corner, with Manvers Street; the huge bulk of Bentinck Court now towers close to where the pub used to be. (A few doors up from the Boar's Head, incidentally, was number 11 Pierrepont Street, where my widowed greatgrandmother Ellen Hardy brought up her children. If family tradition is to be relied upon, however, such a staunch abstainer would never have entered licensed premises.)

Unlike the Wolfe headstone, James Skinner's gravestone seems never to have been photographed while it still marked his burial place, so the exact spot where he lies is sadly unknown. No matter, his memorial at least survives, and with that of General Wolfe contributes to the lively story of human character and endeavour that makes the churchyard such an interesting feature of Sneinton.

Like anything of value. Sneinton churchyard is worth looking after. It is inevitable, however, that while the City Council keep the grass cut and the trees tended, its servants cannot be constantly on the watch to help prevent damage and wanton mischief. That, perhaps, is a responsibility of the local community, and one which, regrettably, is sometimes overlooked. Much time and effort was expended just over a decade ago in recording and securing the gravestones, and it is dispiriting to find subsequent damage to memorials caused by carelessness or vandalism. While it may be merely thoughtless to throw a metal bar up into the horse chestnuts to bring down conkers, it does seriously harm the trees and the memorial stones beneath them, and the practice should be strongly discouraged.

Other damage can only be deliberate. Flat memorial stones which survived unscathed for two centuries have been smashed into several pieces, while other, upright, stones have been broken, or defaced by graffiti and deep scratches. Once these stones are destroyed, remember, they are gone for ever. Sneinton churchyard is a priceless repository of local history, and we cannot just go out and buy a replacement for any part of it that becomes damaged beyond repair.

Throughout the work of churchyard restoration in the late 1980s, much was owed to the unfailing patience, professional skill, and enthusiasm of John Severn, who died in June this year. This brief history is dedicated to the memory of a man who thought Sneinton churchyard well worth cherishing.

I am indebted to several people for assistance during preparation of this article. In searching for facts about James Skinner, I received very helpful information from the Public Record Office at Kew, from Major R.D. Cassidy MBE, Curator of the Royal Green Jackets Museum, Winchester, and from Miss S.L. Davis of East Molesey. To all of these, and to the staff at Nottingham Local Studies Library and Nottinghamshire Archives Office, I express my thanks.

* Frank Smith, in a letter to Violet W. Walker. Reference Librarian and later City Archivist of Nottingham

** The Ionian Islands, of which Corfu is one. were under a British protectorate between 1815 and 1864

< Previous