< Previous

IT PAID TO ADVERTISE:

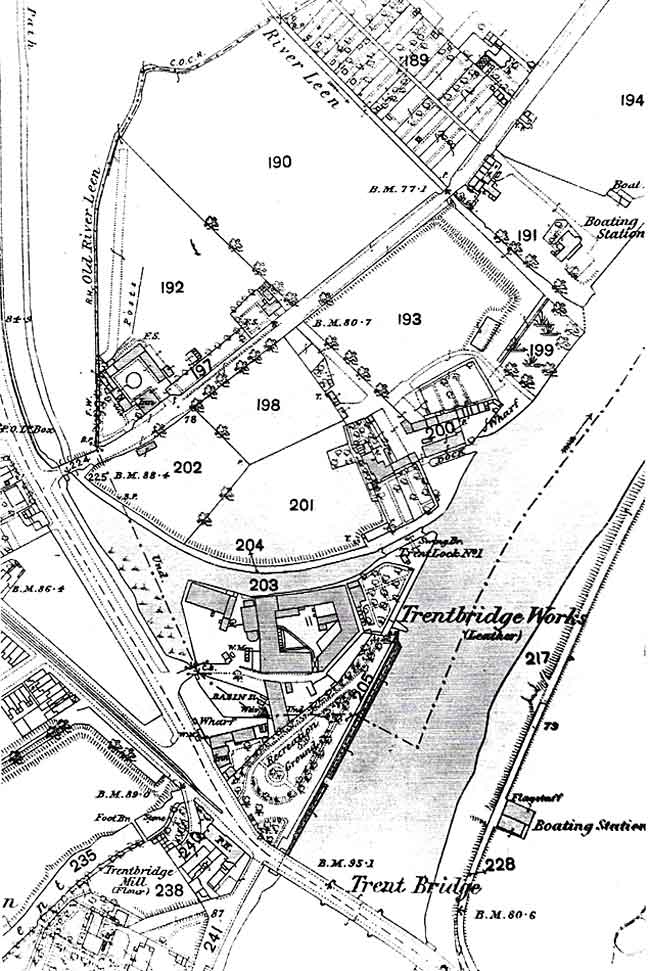

No. 2: the works on Sneinton Island

By Stephen Best

FOR MANY PEOPLE, Sneinton Island would probably come into the same category of unlikely place names as Wigan Pier. Like the famous Lancashire location, however, Sneinton Island really did exist, and in the nineteenth century saw the beginnings of a business enterprise that eventually became one of Nottingham's most flourishing industrial concerns.

Close to Trent Bridge, and just inside the extreme south-western corner of the straggling old parish boundary of Sneinton, lay a piece of land which, though not quite an island, was substantially surrounded by water. On its south side flowed the River Trent, while to the east was the Nottingham Canal, with its entrance lock from the river. The canal ran in a north-western direction from the Trent, and the 'island' was completed by a wide dock, or basin, of the canal, situated on its west side, curving down towards the river. Here in 1861 the brothers John and Edward Turney, already in business in a small way as leather manufacturers in Lincoln, obtained land to build a leather works, and in doing so helped rescue one of Nottingham's old industries from the brink of extinction. Within three years Edward Turney left the firm, to be replaced by his brother William; he, too, soon moved on to set up his own tannery, and John Turney assumed sole charge of the business.

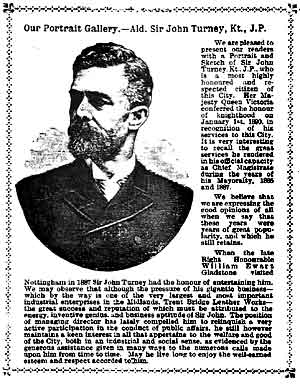

SIR JOHN TURNEY, as shown in the local weekly ’Who, When and Where’, May 22 1899.

SIR JOHN TURNEY, as shown in the local weekly ’Who, When and Where’, May 22 1899.This exceptionally able and energetic man was born in Nottingham in 1839. His earliest education was at a dame school for twopence a week, from which he went on to Lenton National School. After a brief period at Lincoln Grammar School, Turney during his teens attended night classes at the People's College and Nottingham School of Art (then the Government School of Design), being particularly interested in mechanical drawing. At a municipal meeting in 1907, he recalled that he had served an apprenticeship with lace machine manufacturers and steam engine builders, and that when his apprenticeship was over, had had to go out and seek work. 'He added that the Amalgamated Society of Engineers paid him out-of-work money, and he was not ashamed to say that he drew it.' He also related that early in his career he had a shop and workshop in Finkhill Street (just about where the lower part of Maid Marian Way is now), before working for the Lenton leather dressing firm of Bayley & Shaw. Turney's ability as an engineer was to stand him in good stead in later years, when running his large industrial complex.

Having taken over as head of Turney Brothers at about the age of thirty, John Turney devoted so much vigour and vision to the business that by the time it became a limited company in 1888, both Trent Bridge Leather Works and the man who was now its chairman and managing director had attained great distinction. Turney had seen his business grow from a concern initially employing two people, to one with over 400 hands. Widowed in 1866 after a marriage of only a year, he married for a second time in 1870, and had nine children. In 1873 he became a Liberal member of Nottingham Town Council, and was appointed Sheriff five years later. Raised to the rank of alderman in 1880, he became a magistrate and served as Mayor of Nottingham in 1886-7 and 1887-8. This second year of office coincided with Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee celebrations, and so involved Turney in a great many additional public duties. His numerous services to Nottingham were recognized soon afterwards by a knighthood, announced in the New Year Honours List of 1889. On his first appearance at the works after being dubbed a knight at Osborne House, Sir John was greeted with three cheers from his assembled employees, and received an address of congratulation. The newspapers thus summarized his reply to this tribute: 'While the conferring of honours gave a certain amount of pleasure to the recipient, they at the same time involved a serious responsibility. He felt that the honour was really conferred upon the town, he being the trustee, and he trusted that during his life the dignity and honour upon the town would be fully upheld.'

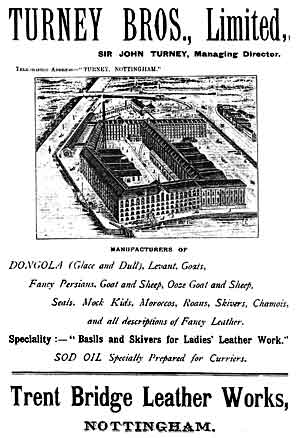

The specialized nature of the leatherdressing trade dictated that most of Turney's advertisements were found, not in the local press, but in national trade periodicals and directories; the technical jargon of the industry alone would probably have made them almost incomprehensible to the casual reader. Early recognition of his achievements, and valuable publicity for his company, came in an article in The Leather Trades' Circular and Review of June 8th 1878. Its writer described Turney Brothers as 'a model leather-dressing establishment', and stressed that no special preparations had been laid on for his visit, as he had arrived, at Sneinton Island without prior notice. In marked contrast to the usual dirtiness of many tanneries, Turney's was scrupulously clean and tidy, and the buildings modern, well-designed, and well- lit. The journalist was greatly impressed on seeing John Turney automatically pick up a small scrap of skin lying on the floor, and throw it on a heap for disposal. Even in those parts of the works where the most malodorous processes took place, the smell was tolerable, and cleaning up was carried out continuously. Any workman who made dust in moving materials about was obliged to sweep it up at once, and the walls of the fleshing-shop, in most works deeply encrusted with filth, were scraped three times a year, while every part of the interior was lime-washed twice yearly. The puring-shop was cleaned out every night; 'pure', or 'puer', was dogs’ dung, the importance of which to the leather trade was vividly explained by Henry Mayhew in his interview with a pure-finder, in London Labour and the London Poor. Mayhew's pioneering account of social deprivation in mid-19th century England is recommended to anyone wishing to get a savour of this branch of the tanning trade. The Leather Trades' Circular was very impressed by John Turney's foresight in having had tramlines laid down inside the works, along which donkey-hauled trolleys conveyed goods and refuse between buildings. On asking Turney how he managed to keep the place so clean, the journalist was told that it was a condition of employment, and that any infringement of the rule meant instant dismissal. Turney claimed that his workmen were the best, and that ’even men from slovenly works speedily fall into the habits of tidiness which they see established here.' The writer considered that only one other tannery, in Leeds, approached the standards he had seen at 'the model works of Messrs. Turney.’

The early 1880s saw several streets of terrace houses built off Meadow Lane, close to London Road, and near the site of the present Notts County football ground. The new mission church of St Christopher, Sneinton, was erected beside the canal to serve their residents, and others who lived in this part of Sneinton parish, remote from St Stephen's church. Many of the houses in these new streets were lived in by employees of Turney Brothers, the first chaplain of St Christopher's remembering many years later that the population had consisted largely of the families of leather workers, and of men who worked on the railway or canal.

Sir John Turney was the subject of an illustrated supplement in a later issue of The Leather Trades' Circular and Review, on March 10 1891, which briefly described the growth of the business from the days when just two people had worked there, to its present state, dealing with 1,700 dozen English sheepskins weekly, together with over 500 dozen East India tanned goat and sheep, and other skins. The firm was also dressing about 1,200 dozens of chamois leather each week. Shortly after the appearance of this supplement, Sir John suffered a heavy personal blow when Lady Turney died of pleurisy and other complications following influenza; aged only forty three, she had been widely respected for her charity work in the town.

Turney Brothers’ works at Sneinton Island, as depicted in 1892. The artist has taken a number of liberties with local topography in this bird’s-eye view.

Turney Brothers’ works at Sneinton Island, as depicted in 1892. The artist has taken a number of liberties with local topography in this bird’s-eye view.Another spotlight was trained on Trent Bridge Leather Works in 1892 with the appearance of Nottingham Illustrated: its Art, Trade and Commerce. Published in Brighton and London, this rather high-class advertising and promotion venture was directed at both a local and a wider readership. After a short historical sketch of the town, the book was divided into three main sections, covering Nottingham's schools, manufacturers, and shops and other businesses. Among the manufacturers Turney Brothers occupied pride of place at the front of their section, being accorded, or paying for, a highly laudatory and respectful feature, extolling the achievements of the company and of Sir John Turney himself. A separate offprint of this was issued, with Sir John’s portrait on the cover, under the title: Nottingham Illustrated in 1892: with a Peep into Messrs. Turney Bros.' Trent Bridge Leather Works, Nottingham. It is likely that Turney’s themselves financed this offprint, for the purpose of sending copies to favoured customers, or others they wished to impress. Included in it was a splendid advertisement, with what can only be considered a rather fanciful engraving, giving a bird's-eye view of Trent Bridge Leather Works. This shows the Trent flowing past on the left hand side, while the entrance to the canal is marked by the lock gates in the foreground. Of the canal basin which made the site almost an island there is, oddly, no sign in the engraving, though it was still in existence at the time. Other aspects of the illustration also fail to convince; for instance, the lock gates, of which one pair is missing, are of improbable design, while the carriageway of Trent Bridge is impossibly wide. The tramway within the works can, however, clearly be seen. And what, one wonders, would ordinary readers have made of some of the products listed below the illustration - 'Dongola (Glace and Dull)’: 'Ooze Goat and Sheep': 'Basils and Skivers': and most of all, 'Sod Oil'?

Sir John Turney was praised in the text for his 'extraordinary energy, inventive genius, and business aptitude', the writer stressing that, besides being chief stockholder and managing director, he had devised and patented numerous improvements in machinery and processes, and was in every way a practical man. In fact, the sheer all-round ability of the firm's head takes some believing, for the article reminded its readers that he was a Member of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, and 'an architect of no mean order'; the Trent Bridge Works had, indeed, been built under his direction, and all machinery and plant fitted from his designs.

The works were described in some detail; the main blocks were laid out rather in the shape of a letter D, with other subsidiary buildings, and the whole site covered some 30,000 square feet. Steam power was used to drive all the machinery, with a separate engine driving the dynamo which provided electric lighting for the entire complex. As in the earlier piece in the The Leather Trades’ Circular and Review, particular mention was made of the 'noticeable absence of any unpleasant odour, so inseparable, as a rule, from establishments of a similar nature.' A system of air propellors, however, effectively disposed of this, and 'even in the 'grain' tanning department, where the old Egyptian method is in force, there is nothing more detectable than the wholesome smell of lime, ammonia, methylated spirits, tan bark, and logwood chips'. (Exactly how wholesome the average member of the public might have found this heady mixture is open to conjecture.) A further aspect of Turney's ingenuity was touched upon; after the works had suffered flooding by the Trent on several occasions, he had supervised the raising of the whole of the yard, boilers, and ground floors by about three feet, and so alleviated the problem.

The chief products of Turney Brothers then were light leather, chamois, and similar goods, made from the hides of lambs, sheep, and calves, with some 450 people employed in the various manufacturing processes. Although trade was increasing, Sir John was planning to bring in new machinery, rather than extra staff, to cope with the work; this was on account of the very time-consuming special training that his employees had to be put through. New tariff rules brought in by the United States had, however, lately brought about a reduction in the enormous quantity of products exported to that country by the firm. Before viewing the rest of Trent Bridge Leather Works, the Nottingham Illustrated visitors were entertained by Sir John in his 'snuggery', adorned, as befitted one of his political persuasion, with engravings of W.E. Gladstone and John Bright. The walls were also enlivened by photographs of some of Turney’s inventions - skin scrubbers, hat linings, and similarly recondite innovations - and with photographs of the factory taken from a report of the Local Government Board, which had pronounced its procedures excellent.

Readers of the article were introduced to other highlights of the works; arcane treatments such as liming, fleshing, bating, and puring, were described. One process was carried out by men called cobbers, who removed any remaining wool or hair from skins; another by fleshers, who scraped off every particle of flesh with knives mounted on beams. After skins had been classified and their refuse removed to make gelatine or glue; they underwent the process of being turned from grains or linings into skivers and chamois. (Skivers were revealed to be split sheepskin leather, while basils, another of the beguiling specialities named in the advertisement, were roughly tanned and undressed sheepskins.) One can imagine the writer of the article struggling to keep up with all the outlandish terms to which Turney Brothers' staff introduced him, and striving to turn his notes into readable copy. Bate, he revealed, was a mixture of 'a peculiar ingredient' and hot water; in the part of the works where this operation was carried out, the managing director's celebrated skin scrubbing device was much in evidence. The journalist and his companions were next shown the fermentation process, followed by the tanning proper. Here he noted the 'numerous sacks of sumacs’, used for tanning skivers, and described the system of drying oiled skins in overhead lofts, where great care had to be taken to avoid the danger of spontaneous combustion. The mystery of sod oil was explained; it was the result of the dried skins being hydraulically pressed until all moisture was squeezed out, and was much used by curriers, who dressed and prepared leather already tanned. Nottingham people no doubt learned with pride that Turney's sod oil was considered the finest on the market.

The warehouses were judged to be very impressive, with innumerable specimens stowed away in glazed cupboards, and the writer was struck by the contrast between the finished products and the dirty-looking skins which had entered the works. Particularly admired were 'some pure larch- tanned ladies' basils, the delicate dove-like tint being unsullied and perfect.' These were used in flower-making, ornamental leather work, gaiters and saddles. Trent Bridge Works had its own machine shop and forge, dye houses, and laboratory; this last was one of the most interesting features of 'this vast establishment', and was under the direction of Sir John's nephew, Joseph Turney Wood, who escorted the Nottingham Illustrated people over the works. Wood had studied at Nottingham University College before gaining practical experience in a tannery on the Continent, where he also visited most of the important leather works and tanneries. J.T. Wood was a notable innovator in the science of leather manufacture, and a frequent contributor to the scientific and trade press; his status within the industry reflected the high place taken by Turney's. The writer left Sneinton Island concluding that: ’We had spent a most instructive time in learning something of this gigantic establishment.'

Sir John Turney's municipal and industrial activities kept him constantly in the public eye, and he was frequently mentioned in the press. The May 22nd 1899 issue of Who, When and Where, a free Nottingham weekly information sheet, featured Turney in its front page series: 'Our Portrait Gallery'. Paying tribute to him, this pointed out that pressure of work had compelled him to give up some of his public duties, though he still took a great interest in the city's welfare. Sir John's portrait reappeared in 1901 in Nottinghamshire & Derbyshire at the Opening of the Twentieth Century - Contemporary Biographies, the accompanying text displaying something of the breadth of his business and municipal interests. Not only was he chairman and managing director of Turney Brothers, but also chairman of the Raleigh Cycle Co., the Clifton Colliery Co., Murray Bros. & Co., dyers and bleachers, of Bulwell, and Hall's Glue and Bone Works Ltd. He was also a director of the Masonic Hall Co. Ltd., and chairman of Nottingham City Council Electric Lighting Committee and General Works and Highways Committee.

In 1909 Sir John Turney left the Liberals over the question of tariff reform, going over to the Conservatives. His change of party allegiance was not entirely unexpected, as he had sat on Joseph Chamberlain's Tariff Reform Commission, and was emphatic that if a 10% duty were imposed on leather coming into the country from America, Germany, or France, he would be able to double Trent Bridge Works in under three years. Unlike many politicians who changed sides, however, he retained his old friendships with his former political asssociates. Although tariff reform caused Turney to join the Conservatives, this policy had split that party down the middle, and had brought about a Liberal landslide in the 1906 General Election.

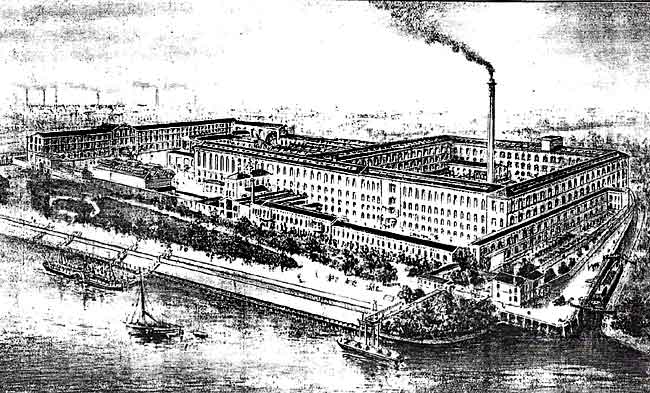

The years before the First World War did indeed see further expansion of the works; the invention of a new method of tanning by chromium compounds made possible the production of harder wearing and more flexible leathers, with an extensive colour range. In 1911 Turney Brothers decided that the original buildings on Sneinton Island were too small for this new process to be accommodated alongside the original method. The canal basin on the western side of the 'island' was therefore filled in, and a new building erected along the London Road frontage to accommodate the chrome tannery. Sadly for the connoisseur of local place names, the disappearance of the basin meant that Sneinton Island ceased to exist from that time. Production started in the new building during 1913, but it very soon had to be given over to making leather for Army clothing for the duration of the First World War. The year 1913 also saw Sir John Turney further honoured by the conferring of the Freedom of the City of London - he had been admitted to the Freedom of the Livery of the Leathersellers' Company in 1906.

Another artist's impression of Trent Bridge Leather Works, as it appeared in the 1914 Chamber of Commerce Year Book.

Another artist's impression of Trent Bridge Leather Works, as it appeared in the 1914 Chamber of Commerce Year Book.A Turney Brothers advertisement in the Nottingham Chamber of Commerce Commercial Year Book for 1914 presents another bird's eye view, this time of the enlarged works, drawn in great detail, and wonderfully romanticized. Like some great palace of commerce, the Trent Bridge Works stand out against a background of the Nottingham skyline punctuated by smoking factory chimneys. People take their ease in the ornamental gardens along the riverside frontage of the leather works, while a paddle steamer and other vessels sail on the Trent. Meadow Lane lock is realistically portrayed this time, with a narrow boat negotiating it, and the whole scene powerfully evokes an atmosphere of the high noon of British industry. The advertising copy accompanying the picture is rather more intelligible to the non-specialist, with some indication of what Turney's products were used for; the particular mention of motor clothing is a sign of changing times. Sod oil makes a further appearance, and 'Crust Sumac Skivers’ add, for the layman with a sumac growing in the garden, a touch of the exotic; the shoots and leaves of the sumac tree or shrub were widely used for dyeing leather. This 1914 advertisement was almost exactly repeated in 1920 in Industrial Nottinghamshire, the text was slightly rearranged in the later publication, while the gorgeous pre-war coloured view of the works was reproduced in austere monochrome.

In March 1916 Sir John Turney's long service to Nottingham was crowned by the Freedom of the City; he was only the sixth man to be admitted as an Honorary Freeman, joining a list that included General William Booth and the Duke of Portland. Liberals and Conservatives alike joined in welcoming this honour. Not long afterwards, in 1918, Turney resigned his seat on the Council, having been a member for 45 years. There was, according to the Nottingham press, 'little, if any, sign of diminishing mental vigour, though his controversial methods had become less aggressive.' Approaching his eightieth birthday, Sir John wrote: 'Don't think I am played out, but the pace of my young friends on the Council is too swift for me.'

In fact Sir John Turney continued as chairman and managing director of Turney Brothers until his death on March 17th 1927, although his son assumed control of the firm towards the end of his father’s life. The company had now grown to one which had branches in Italy, New Zealand, and South Africa. The Nottingham Guardian had wished him well on his 88th birthday at the beginning of the year, remarking that he still went to business nearly every day, and made an occasional public appearance. The Nottingham Journal related that, only a few months before his death, Sir John had been riding in a taxi from his home at Gedling House to Nottingham, when the cab collided with a telegraph-pole in Colwick Road. Though shaken, the old man hailed another taxi and continued his journey. Before becoming the owner of Gedling House in the first decade of this century, Turney had lived for many years at Springfield, his house in Alexandra Park, off Woodborough Road. Seven of Sir John Turney's children survived him, two sons and five daughters. His son John had first worked in the leather business in 1891, and became managing director on his father’s death. Of his daughters, one was the wife of the Nottinghamshire coal owner and ironmaster Sir Dennis Readett-Bayley, while another, who lived in Liverpool, was the mother of the future novelist Nicholas Monsarrat.

The newspapers paid tribute to his great services to Nottingham, and his work on the Council. Much involved with the Tramways and Electricity Committees, he had been regarded as the guiding hand of the latter since the beginning of the Corporation's electricity undertaking. He had also been long associated with the Works and Ways Committee, then the most important of the spending committees of the Council, and had 'controlled the affairs of that important department with wonderful judgment.' Greatly interested in the Trent Navigation, Turney had done much to promote the passing of the Nottingham Corporation (Trent Navigation Transfer) Act of 1915, which secured for the City the navigation rights on the Trent between Nottingham and Newark, and allowed the Corporation to carry out improvements to the locks and other installations on the Trent. The Nottingham Guardian observed that in all respects Sir John was a strong man, to whom, before he had been on the Council for long, others looked for a lead. He was widely respected for his foresightedness, fearlessness, and ready wit, while 'power to drive home his shafts made him a terror to political opponents.' For years he had sustained the dual roles of president of the Liberal Association and leader of the Liberal Group on the Town Council. Mention was also made of his leisure time interests; in particular his membership of the Philharmonic Choir, and of the Nottingham Rowing Club, of which he was the last surviving founder member. As its president he had in 1911 given a challenge trophy to be competed for annually by the four rowing clubs of Nottingham. The glass in the east window of All Hallows’ church, Gedling, was donated by Sir John as a memorial to the men of that parish who had died in the Great War. The papers also remarked on the coincidence of Turney's death having occurred on the day arranged for the foundation-stone laying at the new Council House, successor to the old Exchange, where so much of Sir John's public life had been spent.

This short narrative set out to be a fairly lighthearted look at the advertisements emanating from the Sneinton Island works, but somehow the dominant personality of Sir John Turney has taken it over. Nor did the story of Turney Brothers end with his death. A brief summary of events after 1927 therefore seems appropriate. More buildings were erected in 1932, to make room for new machines, and for the production of chrome leather. The works were kept busy during the Second World War with the manufacture of heavy calf leather for Army boots, though normal peacetime trade was resumed afterwards. At the firm's centenary in 1961, the press reported that Turney's had, despite the demand for chrome leather for shoes, kept up its production of sheepskin leather. Much of this was used in clothing, and the company had established a large export trade to the Continent. It was even mentioned that some large tanned skins were in demand for the making of bagpipes. New machinery had continued to displace the skilled hand worker, but there were still men at Trent Bridge Works with over forty or fifty years’ service.

In 1976 Turney's suffered a fire, which limited production, and later in the decade the demand for shoe leather, by now its main product, declined steeply. A price collapse in 1979, coupled with the problems of the United Kingdom shoe and leather markets, brought about a crisis, and in 1981 the parent company, Booth and Company International (whose group Turney's had joined in 1970), announced that Turney Brothers would close in July, and that its 110 remaining workers would lose their jobs. Most of these were stated to be highly skilled middle-aged craftsmen.

Before long, however, came news that the Nottingham architects William Saunders and Partners were to design a housing development to bring the site back to life. Much of the old tannery building fronting on to London Road was retained, and converted into flats, with the tactful addition of skylights, oriel windows and balconies. Eighty-two new two and three-bedroom houses were built, 36 to the north of the canal, and 46 on its south side, close to the tannery. Turney's Quay, as the new development is named, was completed in 1986, and hailed in the press as Nottingham's own Little Venice. It is not an inapt description of this most attractive waterside site, which provides an agreeable first impression of the City for the traveller coming in over Trent Bridge. Do any of its current residents, though, realise that they are the Sneinton Islanders of the 1990s?

< Previous