< Previous

The Hermitage Remembered:

Recollections of an Old Sneintonian

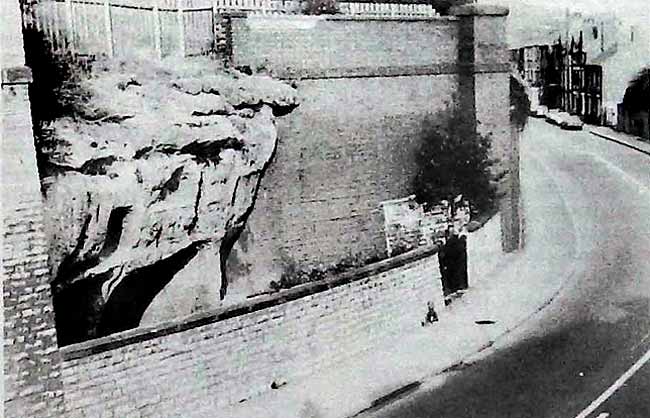

THE HERMITAGE CAVES TODAY Photo Dave Ablitt.

THE HERMITAGE CAVES TODAY Photo Dave Ablitt.Just over eighty-one years ago the Nottingham Weekly Express carried a story about a lady whom it described as 'a very old native of Sneinton'. In its issue of April 24th, 1903, the paper related how one of its reporters had that week visited a Miss Bolderson, who was 'ending her days peacefully and comfortably in one of the almshouses in Park Street'. Miss Bolderson, who gave her age as 85, must have been a resident of what many people still remember as the Collin Almshouses, Friar Lane.

Identifying Miss Bolderson has proved something of a challenge. According to the Weekly Express, she and her family had lived 'in a house on the top of the rock, where Nelson Street is now'. There was in fact no Nelson Street in Old Sneinton by 1903; it was the old name for the thoroughfare which had since the mid-1880s been called Thurgarton Street. The remark suggests in any case that the name Nelson Street was not yet in use when the Boldersons lived there, and, since that street was so called as early as 1844, Miss Bolderson's recollections promised to go back a very long way. This indeed proved to be the case. 'On top of the rock' does seem a rather curious way of describing Thurgarton Street, but, wherever the Bolderson household was, it cannot have been far from Sneinton Hermitage, as the old lady referred to her 'old neighbour and playmate John Blundell'. Then aged 82, and the second oldest living Sneintonian, Mr. Blundell was in 1903 residing at 8 Colwick Road. The family had for years, though, occupied a house in Sneinton Hermitage, where successive John Blundells had been engaged in the joinery trade.

Even the census is of limited help in locating the Bolderson family, as exact addresses were rarely given for the inhabitants of Old Sneinton. In addition Miss Bolderson indicated that she had left the neighbourhood of the Hermitage some 50 years before the pressman visited her. Just to complicate matters further, her surname, although uncommon, was spelt locally in a variety of ways, being rendered as Balderson, Bolderson, Bawderson and Bordison. It was, apparently, under this last variant that Miss Bolderson (as we shall continue to call her) came into the world. The registers of Saint Stephen's Church, Sneinton, record the baptism on March 17th, 1819 of Eleanor Bordison, daughter of William Bordison, labourer, of 'Old Snenton', and his wife Ann. It is evident that by 1851 the family had moved to Windmill Hill Lane, where Eleanor's name was listed in the census as Ellen Balderson, aged 32. Ten years later her name was rendered as Ellenor Bolderson, and as late as 1881 she was still living on Windmill Lane, as it had by then become. The Weekly Express stated that Miss Bolderson had lost her sight about 1891, and it may, perhaps, have been as a result of this disability that she was found accommodation in the almshouse. Despite the paper's comment about her peaceful and comfortable existence there, it seems that Miss Bolderson was not destined to end her days at the Collin Almshouses, for on November 29th, 1904 the registrar was informed of the death, on the previous day, of Eleanor Balderson, aged 86, at her niece's residence, 32 St. James's Street. Cause of death was 'decay of nature'. If this was indeed our heroine, she did at least not have to move far from home during her final days.

In April 1903 Miss Bolderson was 'a surprisingly hale and active old lady', and, thought the reporter 'there are many far younger persons who would envy her health, spirits and activity'. Demolition work on the eastern part of Sneinton Hermitage had recently exposed many caves, and it was to tap Miss Bolderson's memories of the Hermitage and its rock dwellings that the Weekly Express had sent a man to see her. He was not to be disappointed. Miss Bolderson had grown up in the days when Sneinton Hermitage was one of the sights of Nottinghamshire; only five years before her birth Laird's 'Beauties of England and Wales' described it vividly. 'Great part of the village, indeed, consists of the habitations within the rock, many of which have staircases that lead up to gardens on the top, and some of them hanging on shelves on its sides. To a stranger it is extremely curious to see the perpendicular face of the rock with its doors and windows in tires, and the inhabitants peeping out from their dens, like the inmates of another world; in fact, if it was not at home, and therefore of no value, it would, without doubt, have been novelized and melodramatized, until all the fashionable world had been mad for getting under ground. The coffee-house, and ale houses, cut out of the rock, are the common resort of the holiday folks; indeed the coffeehouse is not only extremely pleasant from its garden plats, and arbours in front, but also extremely curious from its great extent into the body of the rock, where visitors may almost choose their degree of temperature on the hottest day in summer.'

When the subject of the Hermitage was brought up, Miss Bolderson immediately observed that several old rock chambers had been broken up when the London & North Western railway bridge was built across it during the 1880s. This short branch line did indeed bring changes to Old Sneinton, including the disappearance of Lund’s allotment gardens on Meadow Lane, and a reduction of 25 feet in the height of the western end of the Hermitage rock. In the process Lees Hill had to be realigned, and Hermitage properties lying in the path of the bridge were demolished. This train of thought quickly took Miss Bolderson back almost sixty years further, and revealed that her memory was still sharp and lively. What she proceeded to describe was an event which had passed into local folklore, the Sneinton Hermitage rock fall of 1829. Although she was only a little girl when it happened, and despite the fact that she was looking back over seventy four years, she had no difficulty in remembering the exact date, May 10th. 'It occurred about midnight' she said. 'It was the day before Barton Wake, and the sons of Mrs. Flinders, who lived in one of the houses, had arranged to take their mother to the wake by boat. That night the sons were 'alarmed by the barking of their little dog, and on going into the cave to see what was the matter they saw that the rock overhead had split in twain. They rushed to their mother, pulled her out of bed, and carried her out as the whole thing collapsed, and a tree which came down with it struck their feet as they reached a place of safety. The occupants of the other house also managed to get out without injury. There was a public house adjoining and half of this was demolished. The landlady was in bed confined at the time, but although half the room in which she was lying was swept away, she was uninjured.' Although her narrative was no doubt tidied up by the journalist before publication, Miss Bolderson's account is graphic enough. She may be forgiven one inaccuracy in attributing to the rock fall of May 10th an incident which actually took place two months later, when another collapse occurred.

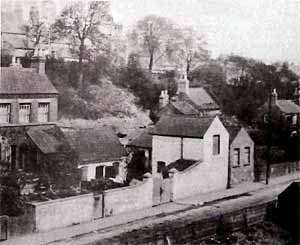

THE WHITE SWAN INN, Sneinton Hermitage: a photograph dating probably from the 1870s. John Eyre was the innkeeper from about 1868 to 1893.

THE WHITE SWAN INN, Sneinton Hermitage: a photograph dating probably from the 1870s. John Eyre was the innkeeper from about 1868 to 1893.Nottingham had been in a state of apprehension about the cliff faces in its neighbourhood since April 13th, 1829, when a formidable mass of rock fell from the back gardens of premises in High Pavement, landing on five houses in Narrow Marsh and destroying them completely. No one was killed in this avalanche, though one or two residents experienced very close calls. As may well be imagined, the Narrow Marsh fall caused anxious eyes to be turned upon the Hermitage rock. In the words of the Nottingham Journal 'Danger was apprehended by the less sanguine, but as no cleft could be discovered, the greater part of the inhabitants connected with the place reposed in fancied security, strengthened by what they conceived the test of time.' Matthew Henry Barker, in his 'Walks round Nottingham', published in 1835 put it more bluntly. 'We come to a public house, the sign of the White Swan. Here a noble dancing room is partly cut in the solid rock, and there were formerly several recesses thus formed. Indeed a mistaken notion seems to have prevailed that however much a rock may be undermined it is still a rock, and therefore can never fall. In this error people had gone on from time to time digging away, and making deeper recesses, without having recourse to arching, till an enormous weight of several hundred tons was left with scarcely any support.'

Such was the background to the rock fall remembered by Miss Bolderson. The Nottingham Review fills in more of the details. At about half past two in the morning, according to its report, Samuel Eyre of the White Swan public house was alarmed by the fall of 'about half a ton of earth through the roof of the back part of his house, into a room adjoining the one in which he slept.' Off went Mr. Eyre to warn the Flinders family next door, but as Miss Bolderson had said, they were already alert, thanks to their dog.

By the first dim light of dawn 'a recent fissure was discovered, completely across the rock chamber of Mr. Flinders' house, and Mr. Eyre found a similar one in his rock dairy, wide enough to admit his arm. Apprehensions were now aroused, and the families from both houses were removed in a state bordering on nudity.' These unfortunate people could only look on helplessly as a quantity of rock estimated to weigh between four and five hundred tons fell on to the Flinders residence and on to the brewhouses, outhouses and bar of the White Swan. The Nottingham Journal related that 'six valuable beehives were destroyed, with about fifty pounds' worth of furniture in the back part of the White Swan.' The Review, while making no mention of the fate of the bees, noted that 'the only animal life destroyed was, we believe, that of a ferret.' Although no human lives were lost, the event made an enormous impression upon the neighbourhood. The Journal likened the noise of the collapsing rock to 'the approach of thunder', and reported that on the following day crowds of people, believed to be in their thousands, flocked to the spot to gape at the scenes of devastation.

All this had occurred towards the western, or Nottingham, end of the Hermitage, where the White Swan, with its adjacent neighbour the Manvers Arms (later Earl Manvers Arms) lay some distance from the foot of Lees Hill. At this point the rock was some forty feet in height, with an overhanging edge. Apparently this had not been regarded as dangerous, since 'there was no weight of soil, or houses to overbalance it.' The rock fall put an abrupt end to this carefree attitude, and the most obviously precarious bits of the rock were immediately cut away. The Nottingham Journal report suggested that Sneinton's lord of the manor was now taking a hand in affairs. 'We understand', it said, 'that it is intended to examine the remainder of the cliff extending towards Colwick, and if all or any of the habitations should be considered unsafe, to take off so much of the face of the rock as will do away with all future apprehension.'

The Journal calculated that the fallen section of rock had been between 25 and 30 yards long, five to six yards thick, and from 30 to 40 feet high.

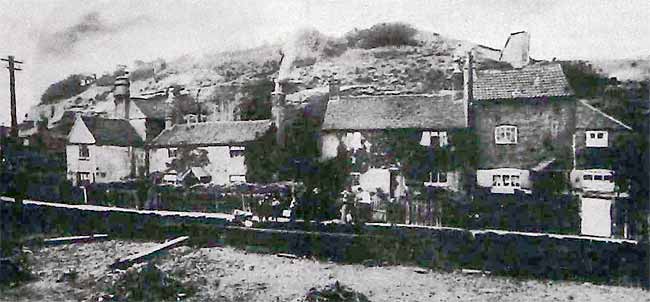

THE HERMITAGE east of the railway bridge. These properties were pulled down in 1903 and 1904. The houses in the background are on Lees Hill Street.

THE HERMITAGE east of the railway bridge. These properties were pulled down in 1903 and 1904. The houses in the background are on Lees Hill Street.The task of making the rock safe evidently proved to be a protracted business, for it was still under way when, on July 8th, Sneinton's second fall happened. The projecting rock was being cut down 'in compliance with the orders of Lord Manvers', when an almost detached piece weighing several tons gave way, a workman who was standing on it leaping to safety in the nick of time. This time the Manvers Arms, rather than the White Swan, was in the way. Down came the rock, said the Nottingham Review, 'upon the roof of the back part of the Manvers Arms public house, where it was quite old and crazy, and broke through the upper storey to the ground floor, where Mrs. Seymour, the landlady then was. She was covered with the rubbish, but was speedily extricated, excessively alarmed and considerably hurt, especially about the face; we are happy however, to learn that she has sustained no injury which is likely to be serious.' This second incident must, one feels, be the one remembered by Miss Bolderson in which a pub landlady was involved. Miss Bolderson thought that Mrs. Seymour had been in bed at the time, but the Journal specifically gives the pleasant domestic detail that she was 'engaged in ironing some clothes.' This seems to have been one detail of the rock fall over which the old lady's memory was at fault. It would be interesting to know whether local Temperance preachers of the day made much of the fact that each time the rock fell at Sneinton it hit a pub. It is easy to imagine the pulpit oratory which might have greeted such an apparent manifestation of Heavenly disapproval of the demon drink. Certainly neither pub took long to recover from the experience. M. H. Barker, writing in 1835, was able to report that 'Both public houses have since the accidents undergone considerable repairs, and are now much improved. At the Manvers Arms the dancing room is entirely in the rock.'

Back in 1903, the Weekly Express reporter noticed that once she had warmed to her topic, Miss Bolderson talked volubly, recalling the names and nicknames of numerous inhabitants of old Sneinton. She was full of stories about the Hermitage and its rock houses. One cavern she remembered as extending for some thirty yards from front to back; it lay, she thought, about halfway between the railway bridge and the police station. It may be that the passage of time had exaggerated the size of this cave in Miss Bolderson's imagination, and it is possible that this was in fact the impressive cavern, about fifty yards from the police station, which was exposed and destroyed in 1903. Though smaller than she described, it was monumental enough, being roughly circular, with a diameter of twelve yards, and about twenty feet high, with six pillars supporting the roof.

Another tale of Miss Bolderson's concerned an unfortunate Hermitage-dweller named Beecroft. He was a sandman, whose work involved him in burrowing into the rock to obtain sand for scattering on domestic floors. Unhappily for him, Mr. Beecroft was suspected of being a Luddite, and it was, in all probability, these unconventional sympathies which caused two legends to be attached to his no doubt blameless person. The first of these alleged that Beecroft had excavated so far into the rock that he eventually arrived beneath Sneinton churchyard, at which point he was forbidden to tunnel any further lest the church become undermined. The second tale had it that in one of the rock chambers behind Beecroft's house a madman was kept chained to the wall. Miss Bolderson recalled that one very large cavern in the Hermitage had been a venue for amateur theatricals and concerts, and that it was reached by no fewer than 52 steps. She also remembered a cave at the foot of Lees Hill in which people had to go down about thirty steps to draw water from a well. Lest anyone should be tempted to identify this as the cave recently cleaned up by members of the Sneinton Environmental Society, one or two points should be borne in mind. As has already been mentioned, the course of Lees Hill was diverted when the railway bridge was built, and the sites of several buildings were obliterated by the bridge abutments. From examining available maps of the area, this writer has come to the conclusion that the Society's rented cave was once behind the third group of buildings to the west of Lees Hill. This consisted of a pair of semi-detached houses, some half-dozen doors away from the Earl Manvers Arms (as it was latterly called). The actual site of the building to which the cave belonged is now under the pavement and carriageway of the present Sneinton Hermitage. The roadway of the Hermitage was widened and pushed up some twenty yards nearer to the rock when the Great Northern line into Nottingham Victoria was constructed in the late 1890s. This brought about the destruction of the remaining houses in the Hermitage west of the railway bridge. All had gone by late 1897 except for the two pubs and one or two cottages, and these, too, followed shortly afterwards.

Clearance of the eastern end of the Hermitage, where the houses now stand opposite the shops, was complete by 1904, and all the new houses were occupied by the autumn of 1906.

Surviving photographs of the old Hermitage, scrutinised in conjunction with large scale maps, lead one to believe that the Society’s cave once lay behind the right hand pair of houses in the accompanying illustrate on. Further evidence suggests that we are dealing with numbers 17 and 19 The Hermitage. No. 17, the one with the creeper on it, was occupied in 1871 by Mary Clarke, a widow, and her family, and in 1881 by the family of William Goddard, a concretor and pavior. No. 19, the taller one, was lived in during the latter years of its existence by Sarah Sheppard, a lace-mender, and family.

Although it is possible to locate the original site of the Society's cave with reasonable confidence, it is not easy to ascertain what it was used for. There are, though, fascinating glimpses of the Hermitage caves in local newspaper reports published as people realised that before long they were going to lose this picturesque feature of Sneinton. 'In two or three of the rock houses' runs one press story 'there is a well, or cistern, cut out of the rock at the bottom of a flight of steps, the permanent water level being only about 10 feet or 12 feet below the level of the road here. Thus the cottagers were able to provide their own water supply without going out of doors for it.' This cutting, unfortunately undated and unascribed, though apparently from the late 1890s, gives some idea of the layout of the rock caverns then exposed. 'Most of the chambers contain a recess in which there is a shelf or ledge 2ft. or 3ft. above the floor and 1 foot deep, which no doubt served the purpose of a cupboard. Some of the chambers had been whitewashed, showing how firm and durable the rock was.'

This same report also mentions one cave which had evidently been used as a stable, since it possessed a manger carved out of the sandrock. This fits in perfectly with another of Miss Bolderson's vivid recollections, for she told the Weekly Express man that 'One family named Tansley lived in a rock dwelling and kept their horse in the same place.' Yet another newspaper cutting (also undated, but probably from about 1893), tells how a party of local notables was conducted through the Hermitage caverns by Mr. W. R. James of Sneinton Hollows, who had the entrance to one of the chambers in his back garden. Among those who saw the sights were Alderman Frederick Pullman of Castle Street, Mr. J. Potter Briscoe, the Borough Librarian, and Mr. Blasdale, Lord Manvers' local agent. They visited one cavern which was being used for the storage of turnips and the cultivation of mushrooms; this cave also contained a scoopwell. Nearby was a cavern in use as a dairy, while another had been originally hollowed out or perhaps modified later for the storage of beer barrels.

Although the Weekly Express had sought her out mainly for her memories of the Hermitage, Miss Bolderson had of course many other local highlights to look back on. She remembered the coming-of-age ball arranged in 1846 for the Hon. Sydney William Herbert Pierrepont, who became the 3rd Earl Manvers in 1860. The ball was held at the Assembly Rooms, Low Pavement, and, claimed Miss Bolderson, her cousin and the young nobleman himself were reckoned to be 'the best-looking lady and gentleman in the room.' Clearly proud of her family's comeliness, she also cited the example of her grandmother, who had once been crowned Queen of the May. According to Miss Bolderson, this lady was a dairymaid at Sneinton Manor, and was married from there.

The final memories recounted by this splendid old lady concerned the Reform Riots of 1831. Miss Bolderson could clearly remember the rioters passing through Sneinton on their way to attacking Colwick Hall. This was an especially vivid memory, as her brother, an outdoor servant to Mr. Musters at Colwick, had been one of the first to tackle the fire started by the mob at the Hall.

Miss Bolderson claimed, incidentally, that the mob had included more women than men, and asserted that the witnesses who gave evidence against the rioters at the ensuing trial had subsequently been obliged to leave Sneinton in fear of attempts on their lives by friends and relations of those found guilty. 'There were shocking doings in those days', she declared. The Reform Riots and their Sneinton aspects deserve an article to themselves, and will have to be dealt with in a future issue of Sneinton Magazine. When that story is told we shall meet Miss Bolderson's brother again, for he was a witness at that trial.

As the journalist rose to leave her, she asked him 'And are you going to put all this in print?' On being told that he was, Miss Bolderson laughed and exclaimed 'Well, I have lived to something.' Indeed she had, and we can be grateful that the Weekly Express learned in 1903 that she was still alive, so enabling us to share her memories of the Sneinton of a century and a half ago.

An old photograph of the HERMITAGE: the sky is touched up by hand. It is thought that the Society's cave lay behind the right-hand houses.

An old photograph of the HERMITAGE: the sky is touched up by hand. It is thought that the Society's cave lay behind the right-hand houses.< Previous