< Previous

UNFIT FOR HUMAN HABITATION:

The Cartergate/Manvers Street Unhealthy Area

By Stephen Best

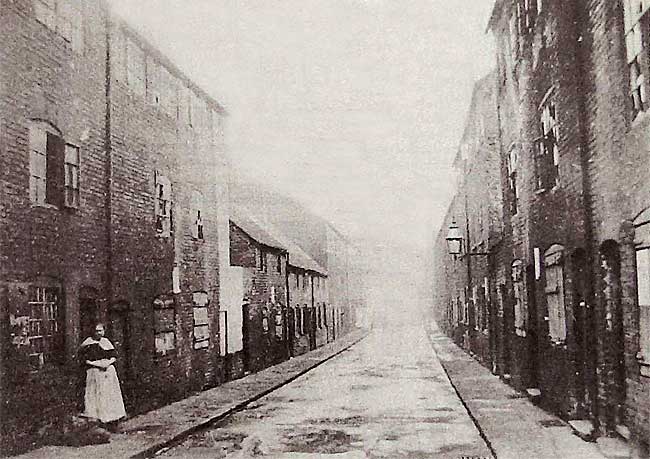

POMFRET STREET IN FEBRUARY 1914.

Of all the areas of land in the Sneinton district, few are as bereft of human habitation as the block bounded by Southwell Road, Lower Parliament Street, Pennyfoot Street and Manvers Street. Given over nowadays almost totally to transport of one kind or another, and dominated by bus garages, this during which the population of the town increased sixfold with hardly any corresponding increase in its total acreage. On Badder and Peat's map of 1744 only the south-western corner of this area was built up, and it formed then the most easterly point of the town. Carter Gate ran along the western edge of this little triangle, with Pennyfoot Stile at its foot and Back Lane forming its eastern side. Beyond Back Lane lay open country leading to Sneinton on its low hill, and dividing the area from Sneinton was the Beck, that stream which had its origin at St. Ann's Well, and ran down to Nottingham and ultimately into the Leen. It still exists, though for well over a century it has been underground, and a part of Nottingham's main drainage system. By the end of the 18th century, when William Stretton drew his plan of Nottingham, there had been some small developments. Back Lane had been renamed Water Lane, and eastward from it ran four short streets. One of these bore the name which is still remembered as the last street-name within the whole block to survive, Stanhope Street. The next thirty years saw a considerable amount of building, with a series of little streets running down into the area from Southwell Road, then named Old Glasshouse Street. Manvers Street had been begun when what was described as 'a mere swamp' was sold for building in 1824. By 1844 the grid pattern of the area was virtually complete, and Edward Salmon's map of 1861 shows it as totally developed. Although by this date the Beck had become a subterranean stream, its course still formed the boundary between the parishes of St. Paul, George Street and St. Stephen, Sneinton. By 1861 Water Lane had become Water Street, and the thirty-seven streets, courts and yards within the area had assumed the plan which was to exist until the whole area was demolished. The main change to affect the district in the late nineteenth century was the extensive programme of street name alterations. The reason for this was the extension of the Borough of Nottingham in 1877 to take in Sneinton, Radford, Lenton, Basford and Bulwell. Each of these settlements had been busily naming its streets for years, and Nottingham suddenly found itself with an embarrassing duplication of names, to the confusion of postmen, delivery men and municipal officials. As a result Sherwin Street and King Street, which ran south from Southwell Road, were renamed Sun Street and Abinger Street. Herbert Street and Eyre Street, in the heart of the area, became Kelly Street and Pollock Street respectively. This must have been a great relief to all, as another Eyre Street, which still exists, lay only a couple of hundred yards away, and a second Herbert Street (renamed Beaumont Street) ran off Sneinton Road. Of the other name changes, the most bewildering concerned Kingston Street, which led from Manvers Street towards Carter Gate. This was renamed Newington Street, while Dennett Street, running up from Manvers Street to the Albion Chapel, found itself named Kingston Street.

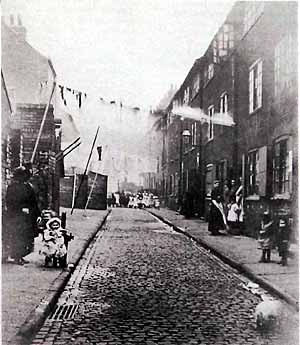

VICTORIA PLACE IN 1912. The dress of the women and children underlines the self-respecting character of the area. The photographer seems to have been at pains to keep most of the children at a distance, but the little girl by the tap nonetheless succeeds in stealing the limelight.

VICTORIA PLACE IN 1912. The dress of the women and children underlines the self-respecting character of the area. The photographer seems to have been at pains to keep most of the children at a distance, but the little girl by the tap nonetheless succeeds in stealing the limelight.Developed as it was before the passing of the Nottingham Enclosure Act, much of the area consisted of buildings whose construction would not have been allowed after 1845, like back-to-back houses and dwellings without yard or garden space of their own. There is sometimes confusion nowadays as to what exactly a back-to-back house was, and it ought perhaps to be made clear that the name applied to a dwelling-house with its back and sides actually built on to similar houses. Such a house, unless it was at the end of a row, thus had only one outside wall, no windows to its back and, of course, no through ventilation. Towards the end of the nineteenth century local authorities were given powers to compel landlords of insanitary properties to put them in order, and then acquired wider powers allowing the compulsory purchase and demolition of whole areas. Further legislation followed, and in 1909 it became illegal for back-to-back houses to be built anywhere; to its credit Nottingham had forbidden their construction sixty-four years earlier. With the weight of the law behind him Philip Boobbyer, the City's Medical Officer of Health, prepared a report early in 1912 for the Housing Committee. In it he declared that the district between Carter Gate and Manvers Street was, within the meaning of the Act, an unhealthy area. Dr. Boobbyer had compiled an impressive mass of data on this small part of Nottingham and through his diligence we have a remarkably detailed picture of an inner-city area just before the First World War.

Despite the renaming of many streets, several names remained to reflect the pre-Victorian character of the area, and in 1912 people were still living in Waterloo Place, Brunswick Place, No Man's Yard, Fredville Street and Hoop Alley. The widest streets were Pierrepont Street and Newington Street, which attained 30 feet from house-front to house-front. At the other extreme were the yards lying between Pierrepont Street and Earl Street; of these, Leopold Place was appallingly poky, being only 6ft. 3in. wide at its maximum and as little as 2ft. 6in. at its narrowest. The area contained, in all, 599 buildings, and of these as many as 432 were back-to-back houses: a look at the 1912 plan will show just how much this sort of dwelling predominated in the area. Of the other domestic properties surveyed there were a few with back windows but without back doors and a further 55 with front and back entrances and windows. On Fisher Gate were the seven almshouses of the Willoughby Hospital. Less impressive, perhaps than they sound, this 'series of small dwelling-houses' was built in 1780 when the Willoughby Hospital moved from Malin Hill. The almshouses were eventually pulled down in the Spring of 1916. Dr. Boobbyer, by dint of careful calculation, arrived at the conclusion that there were in the Carter Gate/Manvers Street area some 1,989 people. It may come as something of a surprise to present-day residents that, just over 70 years ago, this now-depopulated tract of land on the edge of Sneinton was home to about the same number of people as now inhabit the Falkland Islands. If those Nottingham citizens were far from the minds of their country's leaders, they were at least well served in the matter of public houses. The report showed that there were no fewer than eight then licensed and in use. Two of the pubs, the Sinker Makers' Arms and the Half Moon, were on Carter Gate, the latter almost opposite the Nottingham Castle. At the corner of Manvers Street and Pennyfoot Street stood the Red Lion, the other five pubs being close to each other in the middle of the area. These all closed their doors by 1916 and by their passing Nottingham lost some splendid names of the sort no longer favoured by brewers. The Leopard lay at the corner of Water Street and Newington Street, and in the nearby side streets of Pollock Street and Kelly Street were the Lord Holland and the Grey Horse, the landlord of the latter rejoicing in the impressive name John Cariston Westaway. On Pierrepont Street stood the Flaming Sword and between Earl Street and Stanhope Street there lay, appropriately enough, the Earl Stanhope. The inhabitants of the area were ministered to by 63 shops. Of these, perhaps the most familiar names today will be Sandersons, tripe dressers of Carter Gate, and Price and Beal of 12 & 14 Southwell Road, just across the road from their present shop.

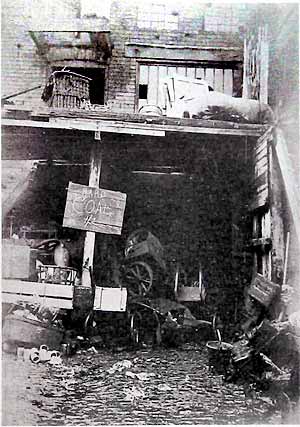

THE YARD AT JOHN STRONG'S MARINE STORE, 91 NEWINGTON STREET, IN 1912.

THE YARD AT JOHN STRONG'S MARINE STORE, 91 NEWINGTON STREET, IN 1912.A wide variety of other business premises existed in the neighbourhood, and the Medical Officer's report recorded two stables, a slaughterhouse, a cooperage, a shoeing forge and a carpenter's shop. Apart from the slaughterhouse, probably the least attractive businesses to have for next-door neighbours in 1912 would have been the five marine stores in the area. Marine store was the rather pompous name given in official publications to rag and bone dealers' premises, and prominent among these at the time was a man with the locally celebrated name of Trickett. We have no pictorial record of William Henry Trickett's shop in Vassal Street, but it must have been chaotic indeed if it rivalled that of John Strong at 91 Newington Street. Mr. Strong's business was on the south side of Newington Street near the corner of Water Street. At the front a signboard advertised his multifarious activities: 'Coal and general merchant; Rags, bones and all kinds of scrap metals; Laces, wool, waste purchased in any amount; Dealer in old iron, old clothes, etc.' Surprisingly enough the sign also revealed that John Strong was on the telephone, number 180Y. Down the adjacent yard was a bewildering confusion of carts, piles of old sacks, boxes and hampers, and discarded rubbish of all kinds. One can only guess at the number of rats that were accommodated in this inner-city hive of commerce.

Of the houses in the Carter Gate/ Manvers Street area, Dr. Boobbyer reported that 201 were 'unfit for human habitation, and irreparable.' A further 242 were 'unfit in their present state, but probably repairable.' This left 156 buildings in the area in a sound and sanitary condition. The irreparable houses were mostly in the area north of Pierrepont Street, with some in Kingston Place, Kelly Court, Smith's Square, Pott's Square and in the streets and courts off Water Street. Of the 201 worst houses in this 'lower class part of the district', only ten possessed an interior water supply. Although 343 houses were not fit to live in, only ninety five were unoccupied. The lowest rents in the area were 2/- a week, paid for houses in Baron Yard and Leopold Place, while the highest were 6/3d. and 6/8d. for some houses in Carter Gate and Manvers Street on the very edges of the area. Among the working population living there were 141 labourers, 46 hawkers and 39 carters, together with eleven miners (who must have had a long journey to work each day) and four canal boatmen. Other male workers in the area included a sawyer, a tinman and a cooper. Of the trades followed by female residents, lace work topped the list with 121, and thirteen of the inhabitants were charwomen. It seems that the deprivation endured by the people of the area was not accompanied by any very apparent lawlessness, as the Medical Officer was told by a senior police officer that in his experience the Carter Gate/Manvers Street area, 'though a very poor district is remarkably free from crime.'

In this respect the area compared very favourably with the Meadow Platts neighbourhood to the north-west of Gedling Street. There was, however, one regard in which the area compared very poorly with Nottingham as a whole, and this was the important matter of public health. Here the evidence was damning indeed, and Dr. Boobbyer's figures spoke for themselves. In 1911 the death-rate for the area was well over twice the average for all Nottingham, while the infant mortality rate was nearly double the rate for the City as a whole; what this meant was that three babies of every ten born in the area died before they reached the age of one year. From these facts and from all the other data he had collected, the Medical Officer could come to only one conclusion, 'that the area in question is unhealthy and that it can best be dealt with under an improvement scheme.'

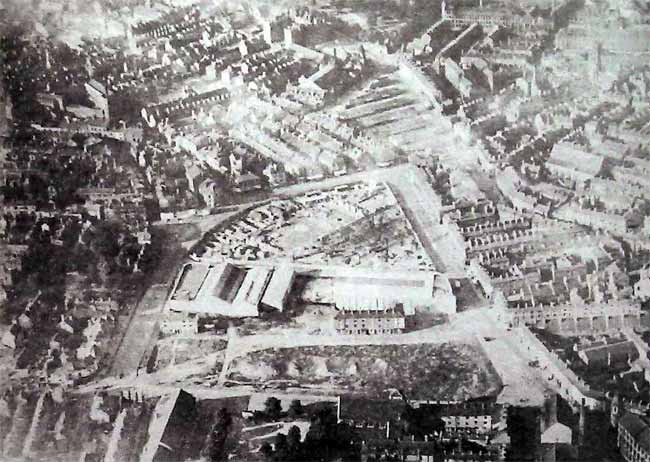

THE AREA IN 1927, with almost all the old property demolished. The new premises of the Carter Gate Motor Co. and Trent Motor Traction are prominent, with the City Transport bus depot and offices in the early stages of construction.

THE AREA IN 1927, with almost all the old property demolished. The new premises of the Carter Gate Motor Co. and Trent Motor Traction are prominent, with the City Transport bus depot and offices in the early stages of construction.Although much of the area became empty during the Great War, little was done to clear and redevelop the district until the early 1920s. When demolition did begin in earnest, it was total, not a single old building in the area being spared. By the autumn of 1921 the first new building had appeared in the shape of the new premises of the Carter Gate Motor Co., built on the comer of Carter Gate and what became known as Stanhope Street. (The old site of Stanhope Street was in fact obliterated, and the new street bearing its name was roughly where Pierrepont Street had run). In April 1923 this new building dominated the almost-cleared area, with just a couple of rows of old houses still standing on Fredville Street and Newington Street. The only other buildings left in the area were one or two shops on Southwell Road, and a couple of warehouses in Patriot Street, which ran off it. In 1925 the decision was taken to build the Nottingham Corporation bus depot and offices at the Southwell Road end of the site, but the first bus garage in the area was the Trent Motor Traction depot on Manvers Street. This was opened in March 1926 at the corner of Stanhope Street and Manvers Street, backing on to the Carter Gate Motor Co. Construction of the Corporation depot began in 1926 and proceeded rather slowly, but motor buses were being garaged in it by April 1928, and in the following June the Head Office Staff were transferred there. When complete, the depot was able to accommodate trams, buses and trolleybuses, there being eight roads with a total capacity of eighty trams. By 1932 the transport flavour of the block had been increased with the arrival on Lower Parliament Street (as Carter Gate had become) of the Dunlop Rubber Co. and Charles Mackintosh Ltd., motor tyre makers. The still-familiar row of shops under the transport offices had now appeared, and in 1932 included the Civic Clothiers, the Meadow Dairy Co., the Home and Colonial Stores, Gardner's Drapery Bazaar, the London & Midland Piano Co. Ltd. and Sydney Flitterman, Clothier. In May 1933 the present Trent bus depot was opened, running through from Lower Parliament Street to Manvers Street. Having space for 145 buses this new garage was much larger than the Trent building of 1926. This was vacated and immediately acquired by the Nottingham Corporation Transport Department, who were able to use it for the night-time garaging of forty motor buses. Owing to an acute shortage of space these vehicles had for about six months been garaged in the former Metro-Cammell factory on King’s Meadow Road, which had been standing empty for some time. The directory for 1941 showed that almost all the area was occupied by the two bus undertakings, the Carter Gate Motor Co. and Dunlop.

For the duration of the War the area witnessed an unremitting slog of hard work as the City Transport and Trent strove to keep a public transport service going beset by fuel shortages, blackout regulations and security rules which, among other things, required the word 'Nottingham' to be painted out on all buses.

Peace has brought a succession of changes to the block. The Corporation bus depot was extended, with the Manvers Street end of Stanhope Street disappearing in this new work. Carter Gate Motor Co. became Hanger Motor, with refurbished premises, and a new firm appeared at the corner of Lower Parliament Street and Pennyfoot Street. This was Steyr-Daimler Puch, which maintained the transport character which the area has now had for some sixty years. If the area is not so rich now in human interest as other parts of Sneinton, no one can grieve for the passing of 'houses, courts and alleys which are unfit for human habitation', and in which 'the want of light, air, ventilation and proper conveniences and other sanitary defects are dangerous or injurious to the health of the inhabitants'.

< Previous